How ‘Fortress Europe’ is welcoming Ukrainian refugees while getting tougher on migration

Many of the EU nations supporting Ukrainians fleeing war have grown increasingly hostile to other refugees and migrants, with violence and pushbacks now widespread, Moira Lavelle and Kieran Guilbert report

Having fled persecution and violence in Iran’s Kurdish region in 2018, Daryan headed to Turkey and spent six months trying to cross the border into Greece - hoping to apply for asylum there and start a new life in Europe.

Daryan - who was 20 at the time - said he was driven back from the border about a dozen times, but is unsure of the exact number because he was pushed back so frequently.

He described a system: men dressed in military fatigues or clad in black and wearing masks who would capture people like him trying to cross the border, detain them for several days, then take them back to the border, beat them, and push them back to Turkey in large groups.

Daryan said his phone was taken every time he was pushed back - meaning he has no video evidence to back up his story - and that his money and even shoelaces were stolen on some occasions.

Today, the 24-year-old lives in Athens, having finally secured asylum last year after three years in limbo and having lost track of how many times he had tried to cross the border only to be beaten and driven back.

But he is deeply resentful of the European Union (EU) for the violence he suffered as well as the repeated violation of his human rights.

“Look I wasn’t like this,” said Daryan, whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

“Sometimes I hate them because of these sufferings. Why, what did I do? Am I a bad person? No,” he told The Independent in an interview. “I came here to fix my life.”

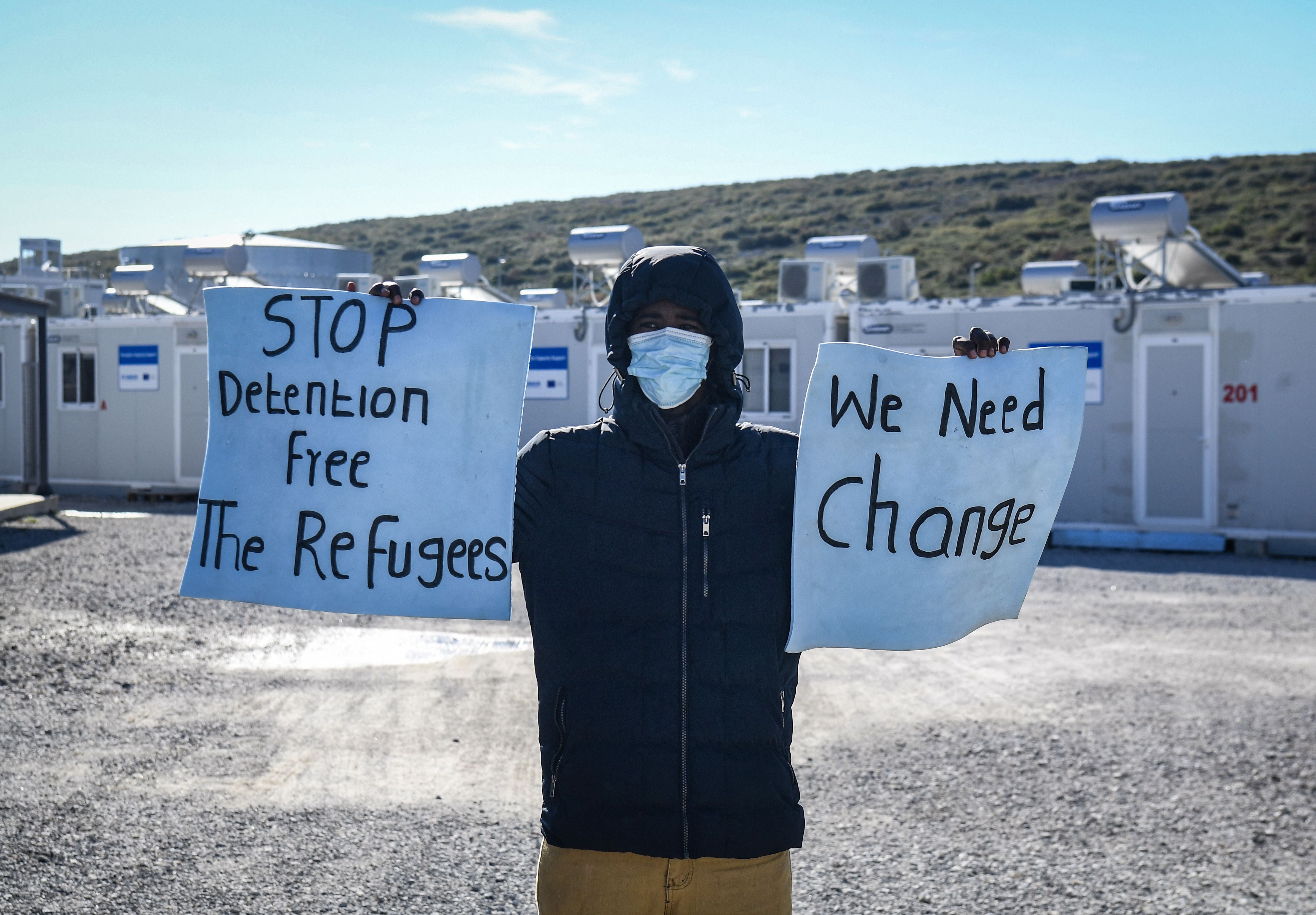

Daryan faced the blunt edge of Europe’s borders, and he is one a growing number of migrants and refugees in recent years to have suffered violence, discrimination and unlawful treatment.

For years, the EU has built walls, increased surveillance, bolstered policing along its borders, cut down on access to asylum, and illegally pushed back thousands of people who have undergone arduous and often dangerous journeys by land or sea to seek refuge.

The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) said last month - just days before Russia invaded Ukraine - that it was “deeply concerned” by rising violence and serious human rights violations, particularly pushbacks, at borders in various European countries including Croatia, Greece and Hungary.

Several such incidents had resulted in the deaths of refugees and migrants, its chief Filippo Grandi said in an unusually strong statement, calling the trend “legally and morally unacceptable”.

“We fear these deplorable practices now risk becoming normalised, and policy based,” Mr Grandi said. “They reinforce a harmful and unnecessary ‘Fortress Europe’ narrative.”

As the war in Ukraine pushes a new wave of refugees into the EU - the number surpassed 2 million on Tuesday and that figure is expected to double - the bloc is having to once again confront questions about what it means to welcome refugees, and who qualifies as one.

The conversation about migrants and refugees rose to the fore in Europe in 2015, when more than 1.3 million people - mostly Syrians - requested asylum on the continent - at that point representing the most applications in a single year since the Second World War.

“Since 2015 when the ‘European refugee crisis’ was declared, there has been an acceleration in the use of measures to deny access at borders to EU and to otherwise prevent people from arriving in Europe to seek protection, regardless of the costs and consequences, and despite the record numbers of displaced people globally,” said Villads Zahle, a spokesperson for the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE).

Access to asylum in the EU has been cut and slowed through several legal mechanisms.

According to the bloc’s 2013 Dublin III regulation, migrants must apply for asylum in the first EU country they set foot in, which has caused severe backlogs in Spain, Greece and Italy and left countless people in limbo for years.

The misplaced focus on security, at the expense of human rights, risks emboldening governments to enact strict border policies

What’s more, in 2016, the EU brokered a deal with Turkey, declaring it a “safe third country”.

This means migrants who cross from there into Greek islands must first prove they were or would be unsafe on Turkish soil before being permitted to apply for asylum - regardless of whatever hardship or persecution they may have faced in their countries of origin.

Then in 2017, Italy signed an EU-sponsored agreement with Libya on migration, agreeing to provide millions of euros worth of financial and technical support to the Libyan Coastguard to intercept boats trying to reach Europe, and return them.

The deal has been widely criticised, especially over the returns, as many refugees are then kept in Libyan detention centres where the UN says the violence inflicted on people may amount to crimes against humanity.

Emily Venturi, an academy associate at Chatham House, said such agreements reflected how transactional and short-term border control had become “Europe’s modus operandi”.

“The misplaced focus on security, at the expense of human rights, risks emboldening governments to enact strict border policies and violate the right to seek asylum, irrespective of the means used by a person to reach safety,” she told The Independent.

Furthermore, for years, EU countries have denied search-and-rescue ships operating in the Mediterranean to dock, and allow people to disembark and apply for asylum. These NGO-run ships have also been repeatedly stripped of their flags, rendering them unable to sail or conduct rescue missions at all.

Deterrence methods at EU borders have also become physical, in a literal sense: walls and fences have been erected recently on the border in Poland, in Lithuania on the border with Belarus, in Greece on the border with Turkey, and in Spain’s Ceuta and Melilla enclaves.

Beyond the legal measures, the EU has increasingly used pushbacks, which Daryan suffered repeatedly, to prevent and deter migrants from reaching Europe.

Pushbacks are a direct violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which states that “refugees should not be penalised for their illegal entry or stay. This recognises that the seeking of asylum can require refugees to breach immigration rules.”

While reports of pushbacks have been prevalent for years, there has been an increase since 2020, particularly in Croatia and Greece, according to campaigners.

There have been reports of pushbacks for years, but an increase in the past two years, particularly in Croatia and Greece:

“Since March 2020, pushbacks have become the norm in the Aegean region,” said Lorraine Leete, a coordinator of the Lesvos Legal Center on the Greek island, also known as Lesbos.

On Greece’s sea border there have been multiple verified reports of people landing on its shores, being gathered by masked men working for the Greek coastguard, put on small dinghies, and abandoned at sea.

A Lighthouse Reports Investigation used video evidence and documents from the EU’s tender database to verify that Croatian police are hunting people trying to cross the border, beating them and pushing them back, with the support of EU funds.

Greece denies pushbacks occur, and has dismissed such reports as Turkish propaganda. Croatia stated last October it would investigate the allegations of pushbacks.

The European Commission has stated it “strongly opposes any pushback practices, and has repeatedly emphasised that any such practices are illegal”.

While the UNHCR’s statement last month was the first time it has acknowledged and denounced pushbacks, some campaigners and analysts do not believe it will have an impact.

Hope Barker, a policy analyst at the Border Violence Monitoring Network, said it had testimonies indicating that UNHCR was not only aware of “systematic and widespread” pushbacks in Greece, but failing to address the issue and even implicit in some cases.

“There’s one (testimony) in which people describe being registered with UNHCR staff in Vial camp (on Chios island) before being pushed back,” she said.

The EU’s stance on refugees and asylum has come under fresh scrutiny once more following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, which has seen people fleeing to seek safety in members of the bloc including Poland, Slovakia, Romania and Hungary.

Ukrainians may enter the EU for 90 days without a visa, and the bloc has stated that due to the war, it will apply a "temporary mass protection" law to extend this residency, and avoid complicated asylum procedures. This is the first time the EU will apply the protection directive, which was established in the 1990s after the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia.

There have been several reports of African students and other people of colour fleeing Ukraine being denied transportation, border crossings, and in some cases facing violence from authorities.

European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen stated that the welcome for Ukrainians should also apply to third-country nationals fleeing the conflict: "Those people must be helped. Moreover, those in need of protection in the EU can also apply for asylum."

While Poland has won widespread praise for how it has welcomed Ukrainian refugees, there were very contrasting scenes along a different part of its border just four months ago.

In November, thousands of people from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan were pushed back by Polish border guards as they tried to cross from Belarus. At least 19 people - infants among them - are reported to have died in the Polish-Belarusian border region amid the standoff between the two nations.

The Polish government has said the country’s actions were legitimate to protect its borders, accusing Minsk of encouraging migrants to travel to Belarus and cross the border illegally.

Many observers and analysts have been quick to highlight the difference in how Ukrainians have been treated compared to the millions of people from Syria, Afghanistan, and other non-European nations who have been arriving on the EU’s shores in recent years.

For example, in Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orban last week said during a visit to the country’s border with Ukraine that “migrants are stopped” while “refugees can get all the help”.

Furthermore, in Greece, Minister of Migration and Asylum Notis Mitarakis recently said arrivals from Ukraine are “real refugees”.

“That is what international law says, not the ideologies of the Left,” he said.

Over the last week, six people - believed to be migrants - were found drowned near Lesbos, while separately, the coast guard said it had stopped five boats carrying more than 120 people from entering Greek waters. Meanwhile, Greece has so far welcomed about 5,000 Ukrainians and offered them automatic temporary protection that applies for at least a year.

This disparity is difficult to accept for people like Daryan.

“I feel horrible,” he said. “What difference do we have (between us)? I don’t know why they do this. They don’t have any humanity.”

The Independent has a proud history of campaigning for the rights of the most vulnerable, and we first ran our Refugees Welcome campaign during the war in Syria in 2015. Now, as we renew our campaign and launch this petition in the wake of the unfolding Ukrainian crisis, we are calling on the government to go further and faster to ensure help is delivered. To find out more about our Refugees Welcome campaign, click here. To sign the petition click here. If you would like to donate then please click here for our GoFundMe page.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments