First Covid, now smog: Delhi’s toxic air shuts schools in fresh setback for Indian pupils

Decision to close school has fuelled concerns that many students could drop out of the education system entirely, reports Namita Singh in Delhi

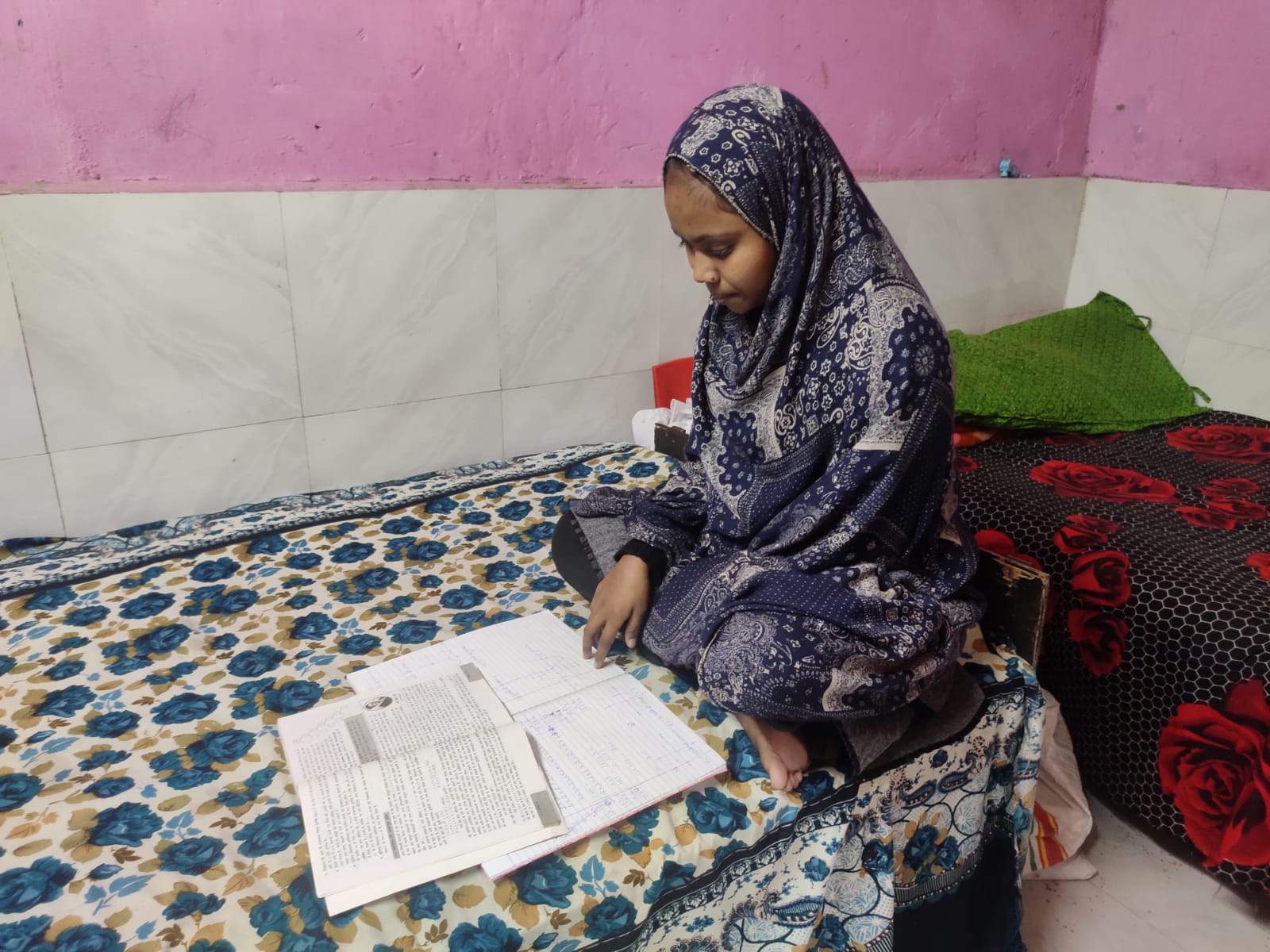

Indian teenager Arzina Khatun had been busy practising for her school’s sports day when the Delhi government ordered schools to shut for four days earlier this month.

Having just returned to class after a year-and-a-half of school closures due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the 16-year-old’s disappointment turned to dismay when a further directive was issued last week.

As air pollution in the national capital soared to dangerous levels, cloaking the city in a thick blanket of smog, the Commission for Air Quality Management for Delhi ordered the closure of all educational institutions until further notice.

Strict lockdown-like measures were first imposed in the city on 13 November, and have been since extended until 26 November.

“We were having sports competition at that point in time, when the government announced closure,” Khatun told The Independent. “I was participating in the marching parade … I had practised for it. And now, it has all gone down the drain.”

Khatun acknowledged the importance of keeping students healthy but believed that the government should have mandated the wearing of masks instead of shutting schools.

The government will consider reopening schools and educational institutions during the environmental ministry’s next review meeting on 24 November.

A toxic haze smothers the capital every year, with Delhi and its suburbs frequently appearing in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) ranking of the world’s most polluted cities.

This year, PM2.5 – a harmful air pollutant that can clog people’s lungs and cause chronic lung and heart disease – has reached close to 400 on the air quality index in several parts of the city.

The WHO considers a figure between zero and 50 to be “good”, while above 400 is “severe”.

Anumita Roy Chowdhury of the Centre for Science and Environment, a thinktank, said school closures were vital to protect children from toxic exposure but called for more sustained government action to tackle air pollution.

“Round the year action is needed to improve mobility and transport to reduce the number of vehicles, ensure clean energy access to all sectors and households, stringent industrial pollution control, strengthening of waste management to prevent waste burning, and adoption of dust management measures in construction and on roads,” she said.

Aarti Khosla, the director of Climate Trends, an NGO working on environmental issues, said shutting down schools was “certainly not a desirable solution, least of all a permanent one”.

“However, given the impact on the health of children, it seems to be the only step to take to contain further damage,” she said.

“When children are exposed to toxic particles and gases at the early stage of their lives, the impact is long term and forever, causing permanent damage to all organs in the body.”

Doctors in Delhi said the increased pollution levels are hitting children the hardest.

“There is of course an uptake in the number of patients with complaints of colds, coughs, breathlessness,” said Shalabh Sharma, an ENT doctor at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in New Delhi.

“A child normally takes a week or so to get better with just a bit of medication. Now, even with medicines, it is taking them longer than two to three weeks to feel better,” he added.

However, the national president of the All India Parents’ Association criticised the school closures, saying that the move disproportionately affected poorer families and could ultimately result in many students leaving the education system.

“If there is pollution in the city, then whether the child is at home, in school or on-road, they will be affected by pollution. There can be no doubt about it,” Ashok Agarwal said.

“I think shutting down school is neither justified nor do I understand the logic behind it,” he said. “The decision does nothing to protect them.”

“How will the government compensate for the loss to the education? It will take decades to come out of it. Children who left the school system and went into child labour and early marriage, how will [the government] repair the damage done?”

Renu Devi, 34, has a family of 10, sharing two rooms in a shanty in Delhi’s Madanpur Khadar. Among these are her four school-going children, who share one phone between them.

“My children are not able to take online classes because if one person sits with the phone for two to three hours, then the battery goes down. It takes another one-and-a-half hours to recharge the phone before the next one has the opportunity to attend the online classes,” she says.

“And besides, ours is a small house. With the inability to attend the classes, how much can you hold a child inside and keep them from pollution?” she asked. “At the end of the day, they will go out and play.”

Khatun dreads reverting to online classes as she lives in a busy, noisy house and must also share one phone with her family members.

“When teachers explain things to us face-to-face, I understand much better than during an online class,” she said. “In school, we participate in co-curricular and other activities. We play and have fun. These things are not possible at home.”

The student also described her disappointment over the fact many of her friends had dropped out of school entirely since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“In the last year-and-a-half, some have also left the school because they were facing a lot of hardships at home. Some had no money to buy books, while others were married off,” she said.

“Since we have lost so many people, my friend and I made a pact that we will stay together and take the same subjects. So that we are not separated again.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments