As Omicron cases grow, why hasn’t India started a Covid vaccine booster programme?

Omicron cases are on the rise in India and the country is blessed with a good supply of vaccines – so why the delay? Stuti Mishra explains

While the Omicron variant has sparked a worldwide rush for more vaccines, with the standard two doses feared to be insufficient, India, where Delta wreaked havoc just a few months ago, is yet to decide whether a third dose is needed.

Early studies show the new variant, discovered in South Africa last month, is not just highly transmissible, but can also evade the protection provided by the standard two doses of vaccines. But its full impact will take time to become apparent.

India has just over 170 cases of the variant, although experts have told The Independent that the figure is “just the tip of the iceberg” as real cases are believed to be much more widespread.

A number of recent cases reported in India are not from other countries but from people with no history of travel, indicating community transmission has already started in the densely populated country.

Last week Delhi recorded its highest number of daily cases in more than four months, at 85 new infections. On Sunday there were 107.

According to Dr Lalit Kant, an independent public health consultant, “it is likely that within six to eight weeks the number of cases may start to rise and soon may overwhelm the healthcare system.

“The decision to give boosters to high priority populations like the healthcare workers, the elderly and those with co-morbidities should be taken now,” he adds. “I think the virus is more widespread than is reported.”

The current tally of Covid cases in India is dwarfed by the figures the country was reporting during its worst outbreak, among the world’s deadliest. However, experts say the country can not afford to be lax.

India’s National Covid-19 Supermodel Committee has said the country will witness an Omicron-driven third wave within the coming weeks, and calls for action, including administering boosters, are growing.

However, despite the preliminary evidence showing the need for boosters, experts say the decision to administer another dose in a country which has a long way to go before covering its massive 1.4 billion population with a standard double dose, is not easy.

The Indian government said last Friday that its first priority will be vaccinating the adult population with both doses of the Covid vaccine – ahead of booster doses.

A government panel is due to meet by the end of the month to review the situation, and may take a call on booster doses. However, there’s a fear that while government ascertains the need in the coming weeks, the country may lose crucial time as Omicron becomes widespread in the coming days.

“Omicron has divided the world into two parts. One part is of the countries that have resources, vaccines, funding and have immunised their population to the best of their efforts, and the second is struggling to immunise even 10 per cent of people. India is in the middle,” says Dr Naveen Thacker, a medical researcher and president elect of the International Pediatric Association (IPA).

“It is not easy to administer vaccines in a country the size of India. There are many factors to take into account,” he adds.

Despite administering more than 1.3 billion doses, India has only managed to inoculate 38 per cent of its total population and around half of the adults. It recently approved vaccines for children, but it still has a long way to go in getting its population double dosed – and now Omicron has changed the definition of fully jabbed.

“The government has two priorities – to provide a second dose to more people and then establish whether a third dose is needed,” says Dr Thacker. “There is nothing wrong with taking the third dose, but the expert opinion on its need is still divided.”

The World Health Organisation recommends booster doses for the vulnerable. However, Omicron fears have led to several countries expanding their booster programme to all adults.

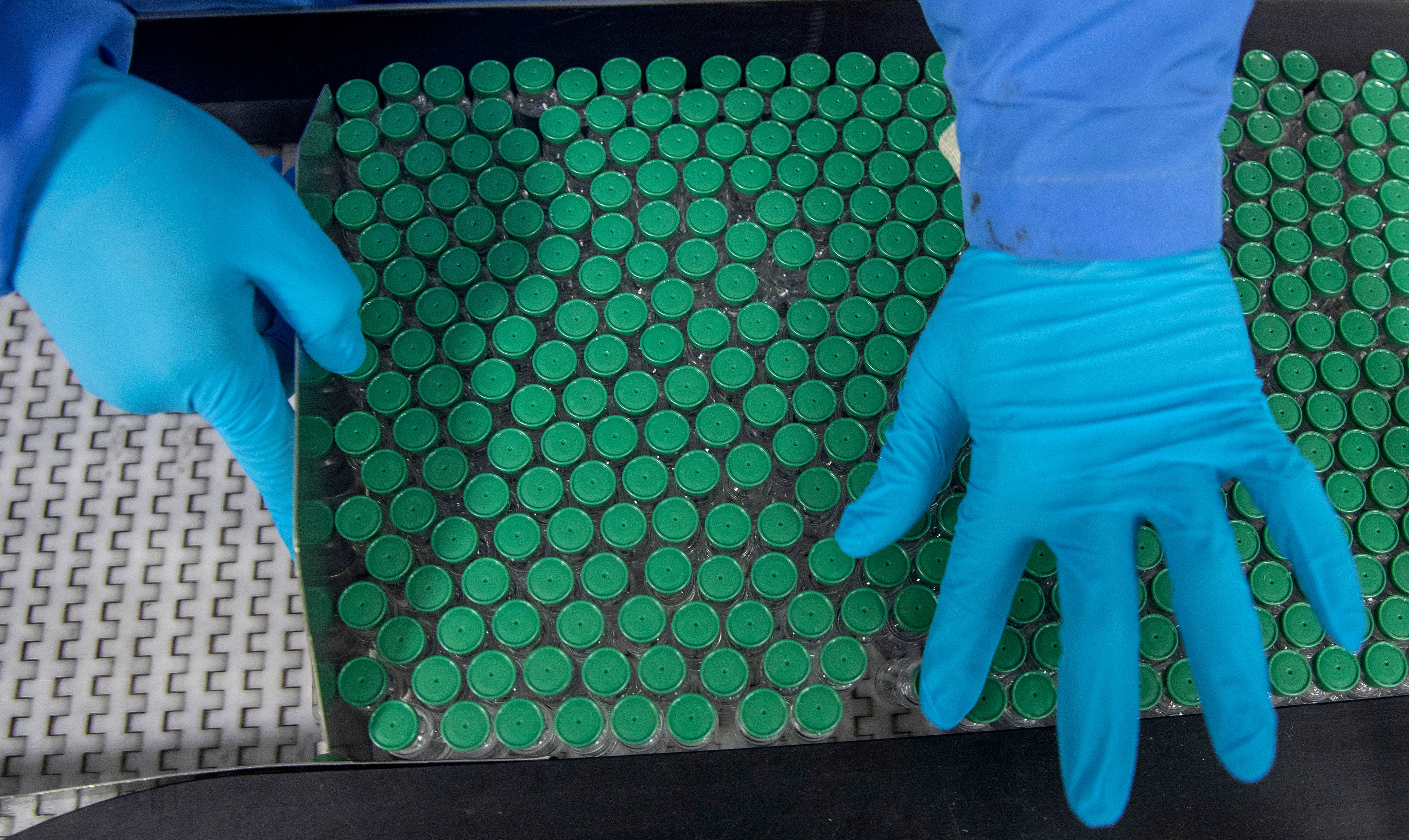

India is home to the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world, the Serum Institute of India (SII). It has so far largely depended on its locally produced version of AstraZeneca called Covishield and its home-grown Covaxin.

“India is in an advantageous position because it can mobilise the extra vaccines needed for booster doses,” says Dr Kant.

While the manufacturers await orders from the government, experts say social distancing norms, masking and Covid-appropriate behaviour is the only way ahead for the country.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments