My biggest fear about the government’s borrowing plans

If people feel poorer – even if they don’t have to sell their home – they will cut back on everything else, and that’s what pushes the economy into a more serious recession, writes Hamish McRae

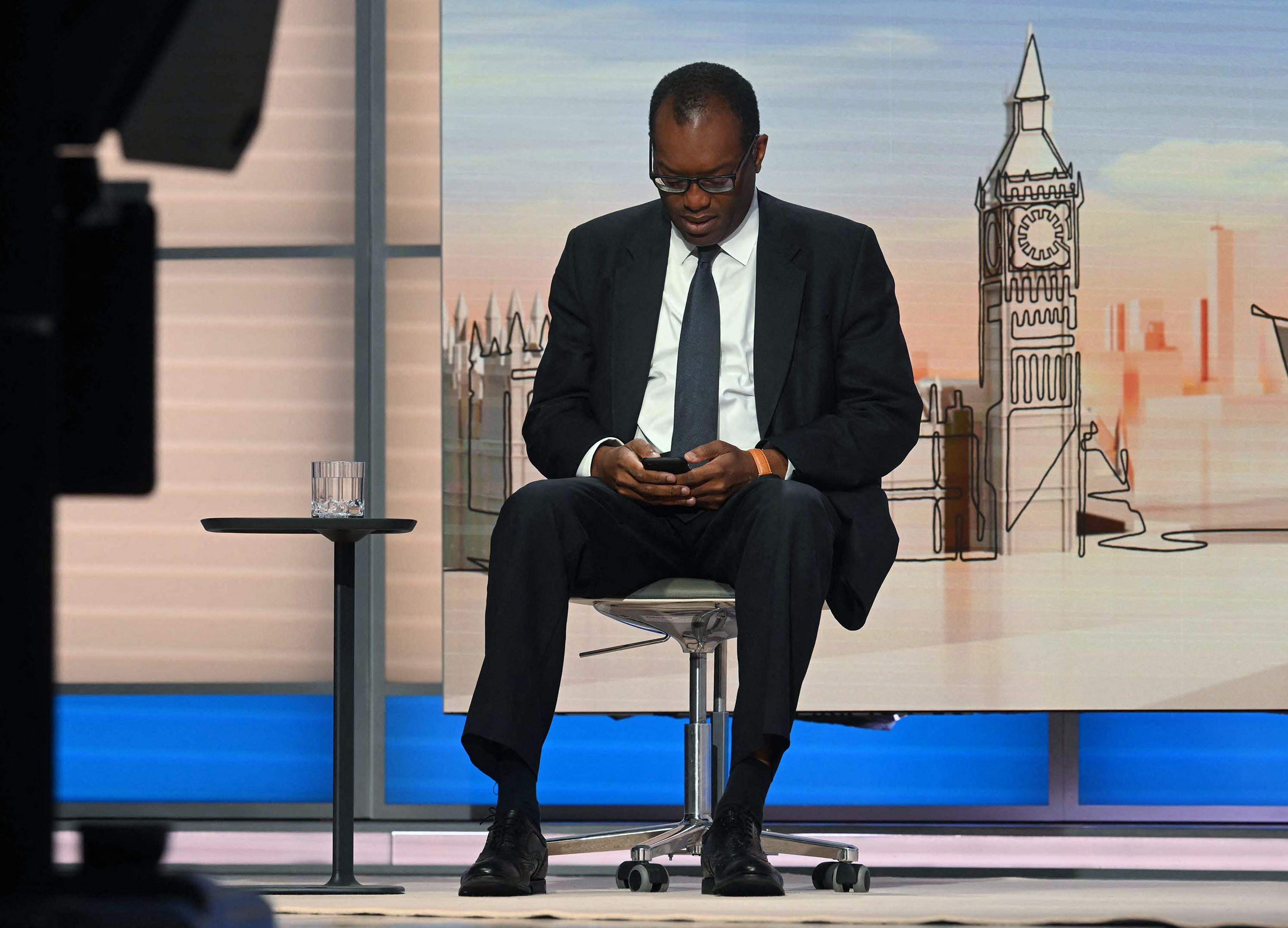

There were two audiences for Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget last week, the British voters and the global markets. The voters will have their say in a couple of years’ time, and will be swayed by the alternative now being put together by Keir Starmer. The markets had their say on Friday – and blew a raspberry.

The pound, already weak, plunged further, particularly against the dollar. Gilt yields, already rising, shot up, with the important 10-year rate going to 3.8 per cent, higher than the equivalent US level. And far from acknowledging that the markets matter, the chancellor doubled down on Sunday, promising yet more tax cuts, leading presumably to even higher government borrowings.

This does not look good. It may be inexperience – or perhaps arrogance – on the part of the chancellor, but if you are going to borrow industrial quantities of cash from people, it is common courtesy to listen to their concerns about how you intend to service that debt.

That said, I think that the dire predictions of catastrophe this week, with the Bank of England supposedly having to make an emergency increase in interest rates and the government having to reverse its policies, are plain wrong. There is no exchange rate target. An increase in rates would be counterproductive. And there is no way this government will change its line.

And in a way, the timing was unlucky. Thursday and Friday were bad days on the markets as they assimilated the impact of the jumbo rise in US interest rates, with bond yields rising everywhere. The dollar climbed against nearly all major currencies, including the euro. While higher bond yields increase the cost of funding the national debt, the overall position of UK finances, while not great, is not too dreadful.

Debt is below 100 per cent of GDP. The average maturity of UK government debt at around 12 years is longer than that of most other countries, so rising rates do not hit us as swiftly as they otherwise would have done.

If the borrowing splurge does mean that we scramble through the winter without a serious recession, then the UK’s finances could look in relatively decent shape a year from now. No bad thing if the world economy does indeed head into a serious downturn.

As in so many aspects of economics, things are rarely as bad, or as good, as they first seem. What has happened is that the financial markets are scared about everything, and Kwasi Kwarteng has given them an additional justification for their fears.

So what happens next? This week will be important. It is possible that the plunge of the pound will continue until it is clear that it has become ridiculously under-valued and bounces back. That has happened before. On 25 February 1985, it went to $1.054, but by Christmas it was back to $1.44. I can’t predict that this will happen again, but merely state what happened in the past. There is a chart of the pound/dollar rate going back to 1971 here.

I think the more important number is what happens to UK bond yields, and if you take the 10-year rate of interest on gilts as a typical cost, that was around 3.8 per cent on Friday. Higher bond yields push up all borrowing costs, including mortgages, and it is a real worry that higher rates could seriously undermine the housing market.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

A housing crash is my biggest fear, partly because it would be utterly miserable for people who have over-extended themselves, but also because of the wealth effect. If people feel poorer – even if they don’t have to sell their home – they will cut back on everything else, and that’s what pushes the economy into a more serious recession.

Eventually we, like other countries, have to work our way towards a housing market where young people can afford to buy their own home. But a long period of stability would be vastly better in every way than the crash of 2023.

Come back to the politics of it all. There are two quite different visions of how to run the economy being developed by our two major parties. Labour’s is the conventional one; that of the New Tories (because this is quite different from the policies the Conservative-led governments have adopted post-2010) the radical one. Both policies will be developed over the next two years and voters will then decide, but their decision will be shaped by what the markets do meanwhile.

If the markets cool down and, maybe reluctantly, accept that Trussonomics does deliver higher growth, then perhaps voters will swing that way. If, on the other hand, they deliver a house price crash, I suspect they will jump in the other direction. Exciting times – if uncomfortable ones.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments