Why an award from Russia could complicate my life

More devious minds might see the choice of a Briton and a journalist as a ploy to banish the negative publicity surrounding the enforced departure from Russia of the BBC’s Sarah Rainsford, writes Mary Dejevsky

In many, but not all, of the past 18 years, I have been one of several dozen foreign Russia specialists invited to spend a few days listening and talking to Russian counterparts from different walks of life.

The meetings, which began as a one-off effort to improve relations, have evolved into something more like an international conference, offering a rare opportunity to meet leaders in a variety of fields, as well as officials and politicians.

Last year’s (virtual) conference included a session with those pioneering Russia’s Covid vaccine effort. This year, there have been panels on different aspects of the pandemic, on 30 years since the Soviet collapse, on the city of Moscow (with the mayor), and on Russia’s approach to climate change in the run-up to Cop26.

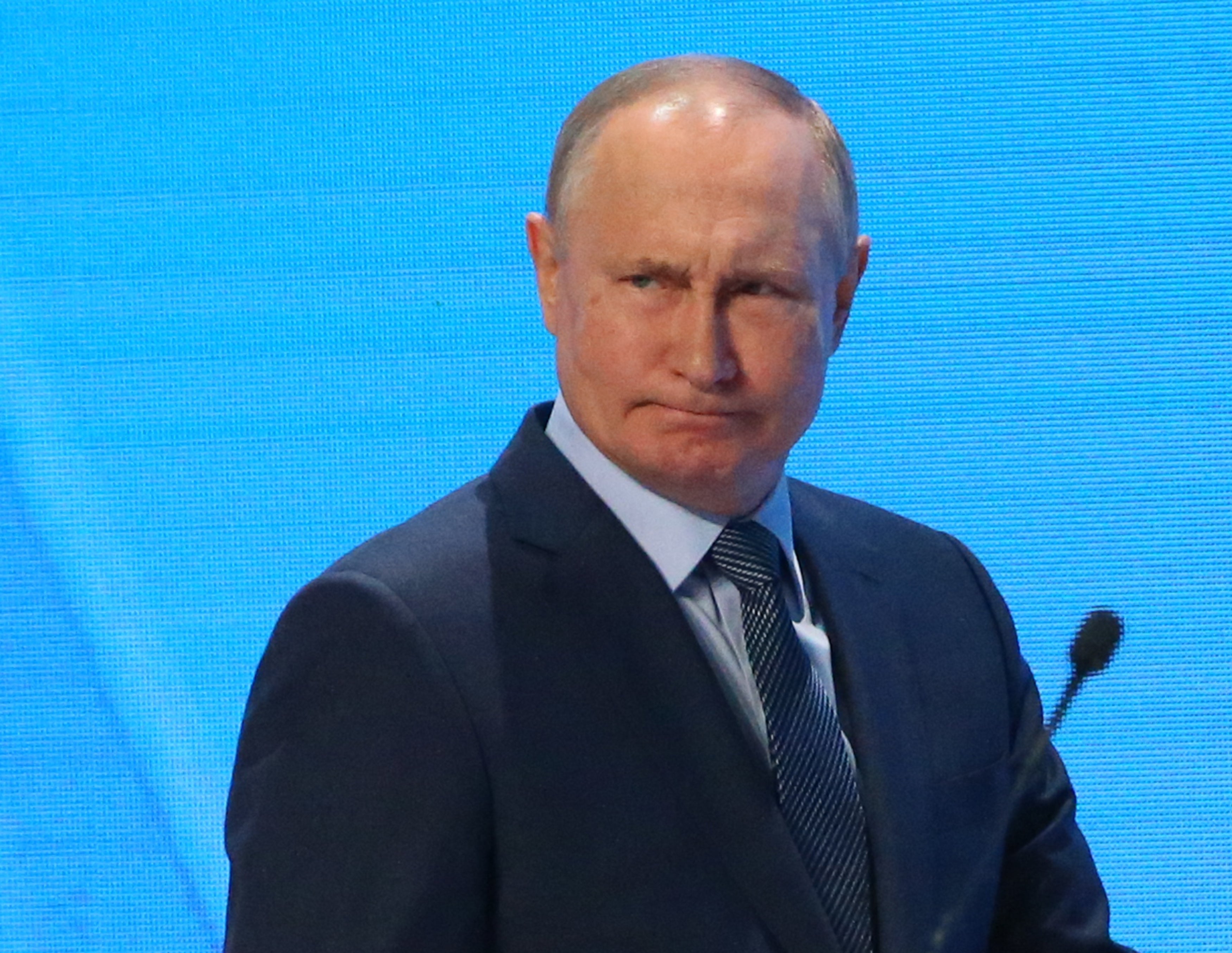

In other words, pretty mainstream conference fare. I should also stress perhaps that such gatherings are not unique to Russia; other countries host similar events. Over the years, if these gatherings have ever made the news outside Russia, it has been thanks to the question and answer sessions with Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, that traditionally happen on the final day. But the association with Putin has had a perverse effect.

As western relations with Russia only soured, those attending what is called the ‘Valdai Discussion Club’ came to be seen as friendly to Putin, although we represent a broad spread of views. “Old Russia hands” might be a better description, as most foreign participants have both extensive experience of the country and a command of the language. That is by way of context. But this year’s meeting sprang a not altogether welcome surprise – for me, that is.

At the opening day’s reception, with roughly 10 minutes’ warning that I had even been nominated, I was announced as the winner of this year’s annual Valdai prize. I gave a short speech of thanks, ending with a comment that some might have found out of place. I said I feared that the award could complicate my life when I returned to London. As it probably will.

On the plus side, the award recognises “outstanding contributions to explaining and promoting understanding of changes that are taking place in global politics”. Explaining and promoting understanding – especially, but by no means exclusively of Russia – might sum up a lot of what my work as a foreign correspondent, and latterly as a commentator, has been about.

Recent award winners include the Russian Middle East specialist Vitaliy Naumkin, and the British historian Dominic Lieven; there is no common political line. But, of course, the sad fact is that an award from a Russian organisation, especially for a British journalist, comes with a taint. A similar award from almost anywhere else might be an excuse to crack open the champagne – even a Chinese, though probably not a Saudi, award might pass muster.

But the image of Russia in the UK is so bad in almost every respect that anything bestowed by a Russian organisation invites hostile questions. You suspect an ulterior motive: “They needed a woman this year” being the least venal.

More devious minds might see the choice of a Briton and a journalist as a ploy to banish the negative publicity surrounding the enforced departure from Russia of the BBC’s Sarah Rainsford, or even a misguided attempt to extend an olive branch to the UK government or British scribes.

Worst of all, you might ask whether the award might be intended to send a signal that foreign reporting from Russia should take the Dejevsky rather than the Rainsford way. Personally, I would rule out the last possibility. But there are still plenty of reasons why any award with a Russian label may be more of a blight than a boon.

After all, the Russian state persecutes and kills opposition figures and journalists, doesn’t it? It hunts down its enemies – Alexander Litvinenko, Sergei Skripal and others – in their country of refuge. Its record on free speech and free elections leaves a lot to be desired. It bullies and invades smaller countries; it flouts accepted international rules. Its despotic leader remains the cold-eyed spy whose first career was in the Soviet KGB, and he has engineered the revision of the constitution so that he can go on and on.

At which point, let’s pause. It is rushes to judgement and simplistic stereotypes such as these that I have tried over the years to question. The reality is often more complicated than it looks, and it is worth having an awareness, at very least, of how it was to live in the closed country that was the Soviet Union (when I spent a year as a British Council exchange student in the Russian provinces), or how it was to experience the disintegration of the Soviet Union (I was then the Moscow correspondent for The Times).

These are the formative experiences of at least half of today’s Russian population, including Vladimir Putin, and supply the prism through which they view their country. It helps to explain why – to date, though maybe not for ever – a majority have preferred the stability and vastly improved living standards they enjoy under Putin to any alternative that might be on offer.

I have visited Russia regularly over the past 20 years, noting the bad, but also the good, that has come Russia’s way. Where the state crosses a line, as in snatching Crimea from Ukraine, I try to explain how the view from Whitehall or the Baltic capitals might differ from that of the powerholders in the Kremlin. I am also extremely wary of any news story that touches the world of intelligence – as much does in UK relations with Russia. There is a great deal that we do not know.

My view of today’s Russia is essentially as a defensive state, which has watched not only the depletion of its territory with the Soviet collapse, but the nigh-elimination of what it surely saw as its security buffer – as Nato and the EU expanded to the east, then made grabs for Georgia and Ukraine.

I see Putin as a single-minded defender of Russia’s national interests, whose prime objective has been to give Russians a better life at home and restore what many Russians saw as their lost dignity abroad. To me, as a long-time Russia watcher following the developments of today, this makes sense.

It is not, though, the official and dominant interpretation of Russia as it is presented in the UK today. And the consensus, according to which Russia is an aggressive and expansionist power with a leader whose prime aim is to repress his population and disrupt the west, is not unique to official circles in the UK. It prevails in the United States and in most parts of continental Europe.

Where the UK stands apart, however, is in the absence of any public debate, and what seems to be a cast-iron assumption that hostility rather than rapprochement is how relations must be until Russia – like a difficult toddler – is “persuaded” to “change its behaviour”. My case is that it won’t, until it feels more secure than it does now, and that the UK in particular has been grievously misreading Russia for most of the past 20 years.

A small minority of UK Russia-watchers share this view. And the thanks that we get is to be branded a “Kremlin stooge”, a “Putin-apologist” or a “useful idiot” without eyes to see.

Anyone who so much as queries a dot or comma of the UK’s official Skripal narrative is labelled a “conspiracy theorist” to boot. And now, for me, comes the Valdai award – proof positive of my treachery for those who, earlier this month, following a rare Chatham House debate on Russia policy, accused me of parroting the Kremlin’s critiques.

Nor does it end there. The logical extension of this line of attack is to argue that, if I am “in the pocket of the Kremlin” on this, how can you respect my judgement on anything else?

Let me offer two responses. First, given that the Russo-phobic consensus has so abjectly failed to tame Russia at all over the years, why not at least try a different approach?

And, second, more broadly. Among the mistakes identified by MPs in their recent report, ‘Coronavirus – Lessons Learned’, is the prevalence of “groupthink” in government and scientific circles and the need for a “red team” to advance another view. Ditto the UK’s Russia policy.

It is beyond time that the consensus was challenged. Regrettably, I fear that the Valdai award for this British journalist will have the opposite effect.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments