Rishi Sunak has charted a credible path, the economic growth figures are good news

If interest rates remain low Britain’s debt can be serviced comfortably. If all goes to plan, by July next year the economy will be back to how to was at the end of 2019, writes Hamish McRae

Look at the numbers rather than listening to the words. That is the rule of thumb when assessing budgets. An adept chancellor, and we have one here, will frame the Budget in a politically-artful way. So we have the bow to this chunk of the voters, to that bit of the country, to those people most acutely hit by the current emergency. There is the assurance of government help, coupled with the emphasis on fairness as to who pays for it.

Behind those words, however, are the numbers. Those come from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and in short, those numbers this year are dreadful – but not quite as dreadful as appeared likely even a few weeks ago. The economy seems to be performing a touch better than feared. While more money will be pumped out over the next few months than seemed necessary last autumn, it may be possible scramble through without the sharp increases in taxation many had feared. There is a bill to be paid and the real burden of taxation will rise, but we will not be clobbered in the way that many had feared.

Two numbers – and a date – matter the most. The first number is public sector debt. Before the pandemic struck it was 80 per cent of GDP. Now it is projected to top out at just below 110 per cent of GDP in three years’ time. (The figure in the Budget speech of 98 per cent of GDP does not include debt held by the Bank of England.) The increase in debt will hang over the country for many years, as Rishi Sunak acknowledged. But by world standards, it is middle of the pack: very roughly the same as that projected for the US, worse than Germany, not nearly as high as Italy or Japan. If interest rates remain low that debt can be serviced comfortably. If interest rates go up, there will have to be some way of paying them, either by further tax increases or cuts in projected spending.

The second number is tax, also as a percentage of GDP. Taxes currently account for about 34 per cent of GDP. The government has other income, from interest payments and such, which bump up the total revenue to about 37 per cent. That total is now projected to go up to 39 per cent in four years’ time. That will be the highest it has been since the early 1980s. That increase comes about by two means. One will be the rise in corporation tax rate from 19 per cent to 25 per cent. The other, a larger portion, will come from what is called fiscal drag – holding income tax thresholds down while inflation chips away at the real value of incomes.

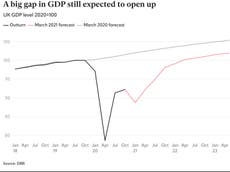

Now the date. It is 1 July 2022 – the middle of next year. That is when, if all goes to plan, the economy is back to the level it was at the end of 2019 before the pandemic struck. That is six months earlier than the OBR expected last November. That is good, though not as good as the US, which hopefully will be back by the end of this year. The timing matters enormously because the faster we get back to full output the faster public finances can be repaired: tax revenues come up and support payments can go down. Even a couple of months make a huge difference. If growth at the back end of this year is better than expected (and the Bank of England is hoping for a big bounce) then everything will look brighter come the autumn.

And the rest of the announcements, the help to grow, the free ports, the change of the remit for the Bank of England and so on? That is fine. We have a lot of experience of such initiatives over the year and we know some are successful and some are not. Let’s hope this crop surprises in positive ways. If they can genuinely increase the growth potential of the country that would be most welcome. But ultimately budgets are about numbers – about how much it takes in tax, how much it borrows and how much it spends.

The chancellor has charted a path that is just about credible. It will be accepted as such by the global financial markets, where confidence in the UK has started to return. But we need several years of solid growth to fix the nation’s finances. Fingers crossed we get them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments