Europe’s great problem? We simply don’t have a reliable enough power supply

The energy supplies of the UK and Europe have become more fragile for technical reasons – our reliance on wind and other irregular sources – and for political reasons, notably reliance on Russia, writes Hamish McRae

If we are all going to drive around in electric cars, which we are, we need a reliable electricity supply. We don’t have one. However fast we build alternative sources of power generation, we will still need gas as a standby fuel. We don’t have enough storage capacity for gas. As for nuclear power, there is a multiplicity of troubles in building new stations. It is a mess.

That mess is not confined to the UK. There are some home-grown stupidities, like creating a regulatory structure that has encouraged people with little experience to start up all those little energy suppliers that are going bust. You can understand the motive of wanting to inject more competition into the industry, and we have Ofgem, the regulator, created in 2000, which begins its mission statement: “We work to protect energy consumers, especially vulnerable people, by ensuring they are treated fairly and benefit from a cleaner, greener environment.” That is fine – but actually its main job should surely be to keep the gas flowing and the lights on.

But the mess is more broadly a European one, and indeed a global one. If you travel to some emerging economies, you expect power cuts. That is why so many places have standby generators. But you don’t expect that in the developed world. Here is a snapshot of the problems across Europe.

The UK has just started operating a power connection with Norway, via the longest under-sea electricity cable in the world. The idea is to bring clean hydropower from Norway and export clean wind power from the UK. But one problem is that there has been a drought in Norway, leaving reservoir levels at their lowest for 10 years. So not only will exports have to be limited, but Nordic countries face very high power bills – five times the level of a year ago. As for our plan to export wind-generated power, that is fine as long as the wind blows.

And look at Germany. It has made huge strides in switching to renewable sources of power, but in the first half of this year, coal and lignite (brown coal) provided more than a quarter of its energy. It will be tough to cut that further when the country shuts down its remaining nuclear stations. (Last year, less than 2 per cent of the UK’s electricity came from coal.)

As for France – the country that made a huge bet on nuclear power – last year nuclear provided 70 per cent of its electricity, the highest proportion in the world. France is the largest exporter of power, including some to us. But total capacity has not risen since 1999, and is actually slightly lower now than it was then. The average age of its 58 reactors is 35 years.And take Italy. Fossil fuels supply more than 60 per cent of the power it generates, with imported gas being by far the largest element in that mix. We know what has happened to gas prices.

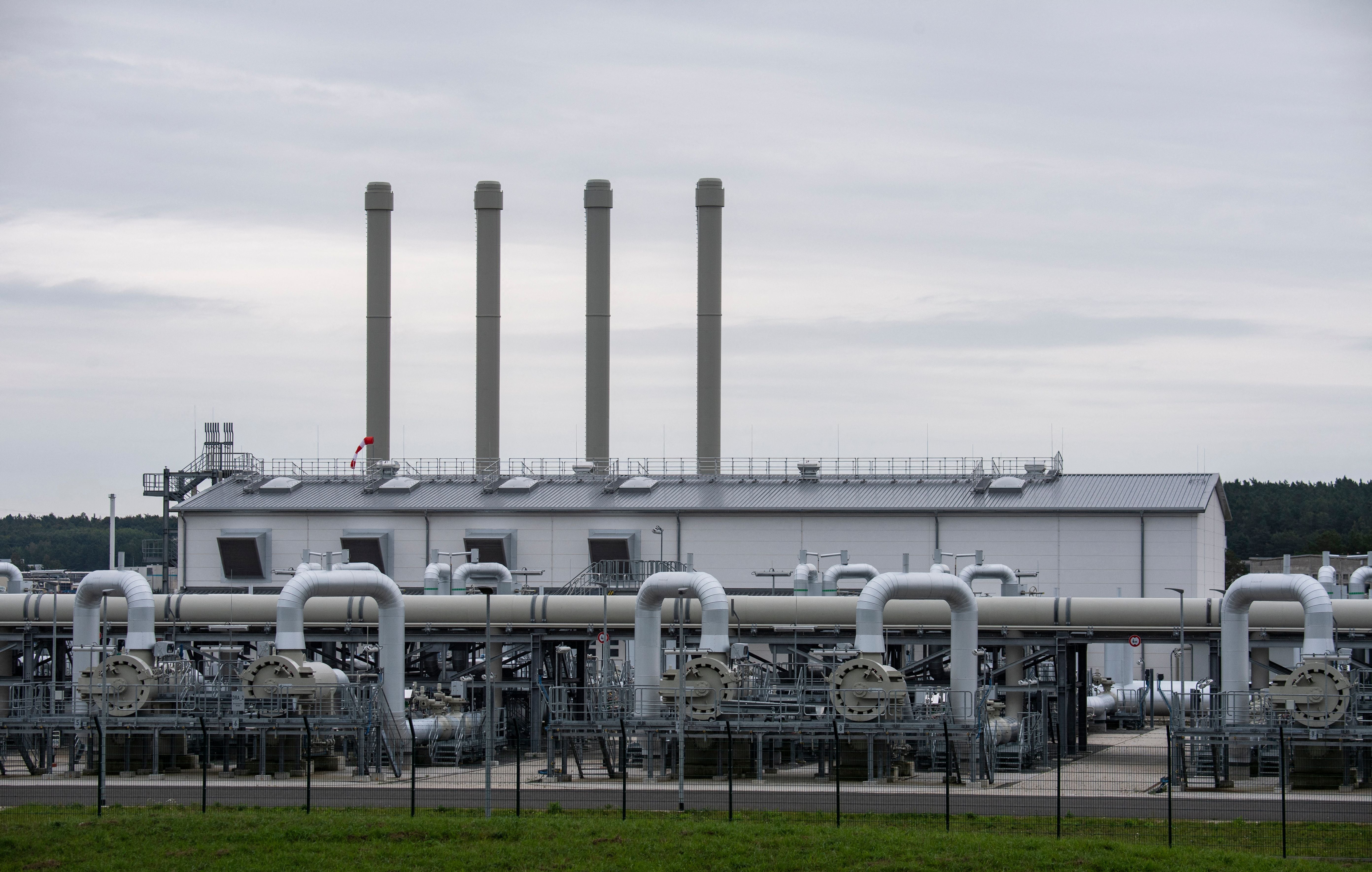

Indeed, the whole debate about Germany completing its new gas pipeline down the Baltic from Russia – Nord Stream 2 – is whether this makes Europe more or less vulnerable to pressure from Russia. It is a complicated story, but because it bypasses the existing network that runs through Ukraine, there is certainly a strong argument that Russia can now use energy more effectively as a weapon against Europe, should it choose to do so.

The core point here is that the energy supplies of the UK and Europe have become more fragile. They have become so for technical reasons – the reliance on wind and other irregular sources – and for political reasons, notably our reliance on Russia. Add in the UK’s incompetence over regulation, France’s difficulties over building new nuclear power stations, and Germany’s rejection of nuclear altogether, and the prospects are not good.

Perhaps most troubling of all, this comes at a time when the world economy is in the early stages of a seismic structural shift away from reliance on fossil fuels and towards carbon neutrality. I am worried that a most admirable aim – cutting carbon output – will be undermined by incompetent execution. We will make people switch to electric cars, but we won’t be able to generate the electricity to power them.

What may happen this winter – unless we get lucky and it is a warm and windy one for the UK and Europe – is that there will be power cuts. Warmth cuts the demand for power, while wind increases supply – but of course the reverse may occur. Power cuts will be alarming and people will demand action. We should not have got ourselves into this position, but unless we create a more robust power supply, people will have every right to be angry.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments