It’s time to bust some of the myths surrounding monkeypox

As with Covid, monkeypox has mutated – so although there are some similarities with the original version, the current variant has distinct features that we are only just beginning to understand

Time is a critical asset for gathering intelligence about infectious disease. Think back to how little we knew about Covid-19 when it emerged in the UK in 2020. Over the ensuing weeks and months, treatments were developed and we began to identify those most at risk of developing symptoms and requiring admission to hospital.

But, just as time is an asset in understanding infectious disease, it can also prove the greatest threat to those unfortunate enough to be the first to contract a new variant – some of whom will go on to pay with their lives.

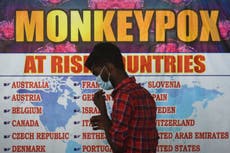

We are still learning about the latest infection threat: monkeypox. The first case in the UK was identified in late May of this year – and by the middle of July, 1,735 people had been diagnosed with the infection.

What also emerged relatively quickly is that this disease was spreading among specific groups and geographical areas. Some 96 per cent of cases were found in men who have sex with men, with three quarters of cases pooled in London, with charities warning about stigmatisation of gay and bisexual groups amid the outbreak.

We still don’t know much about the origins of this virus, although there is suspicion that rodents were vectors of the infection. This is not a new disease – the first human cases were identified as far back as 1970.

As with Covid, monkeypox has mutated – so although there are some similarities with the original version, the current variant has distinct features that we are only just beginning to understand. It is likely that more specific features will be discovered in the coming weeks and months.

From the start of the monkeypox outbreak in the UK, the most commonly described and identified symptom was a skin rash on varying parts of individual bodies. Rashes are not uncommon and could be caused by a range of conditions such as chickenpox, so in itself its not a particularly helpful diagnostic symptom. However, recent research has been able to help pinpoint more specific symptoms which should improve diagnosis and more rapid and precise treatment. These include penile swelling and rectal pain.

They also found that – contrary to UK Health security Agency guidelines – almost half the cohort included in the research developed lesions to the genitals, anus or area around the mouth, after (rather than before) these other symptoms appeared.

Another revelation was that a third of the participants had a sexually transmitted infection such as gonorrhoea. Not only does this aide diagnosis, it points to the importance of screening all those who present to healthcare with sexually transmitted infections as a useful way of picking up unidentified monkeypox cases.

This new intelligence not only helps with diagnosis but identifies those at greatest risk. Given the supply and distribution problems there have been with the new monkeypox vaccine, knowing who is at greatest risk could help prioritise specific groups at a time when supplies are scarce.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The difficulty will be in providing and delivering this targeted vaccine programme in a way that doesn’t further stigmatise a group that are not unfamiliar with bigotry and misinformed prejudice. Given the strong hints from prospective conservative leader Liz Truss and others about radically shrinking the role of public services to save the public purse, any further cuts to sexual health services would be both tragic and foolish.

Even if you don’t care about the plight of those affected by monkeypox, and some don’t, then the economic argument for investing in services now to prevent an acceleration in infections – and all the associated medical costs – should be enough to convince you.

It was a Conservative government that boldly and rightly stepped up when HIV emerged in the 1980’s. We need the current Conservative government to repeat that strategy.

There is much to be praised for the way they intervened 40 years ago, but mistakes were made. Learning from those mistakes would be an intelligent and humane approach to the latest threat from an infectious disease.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments