Mea Culpa: the uses and abuses of pop music’s past

Questions of language and style in last week’s Independent, reviewed by John Rentoul

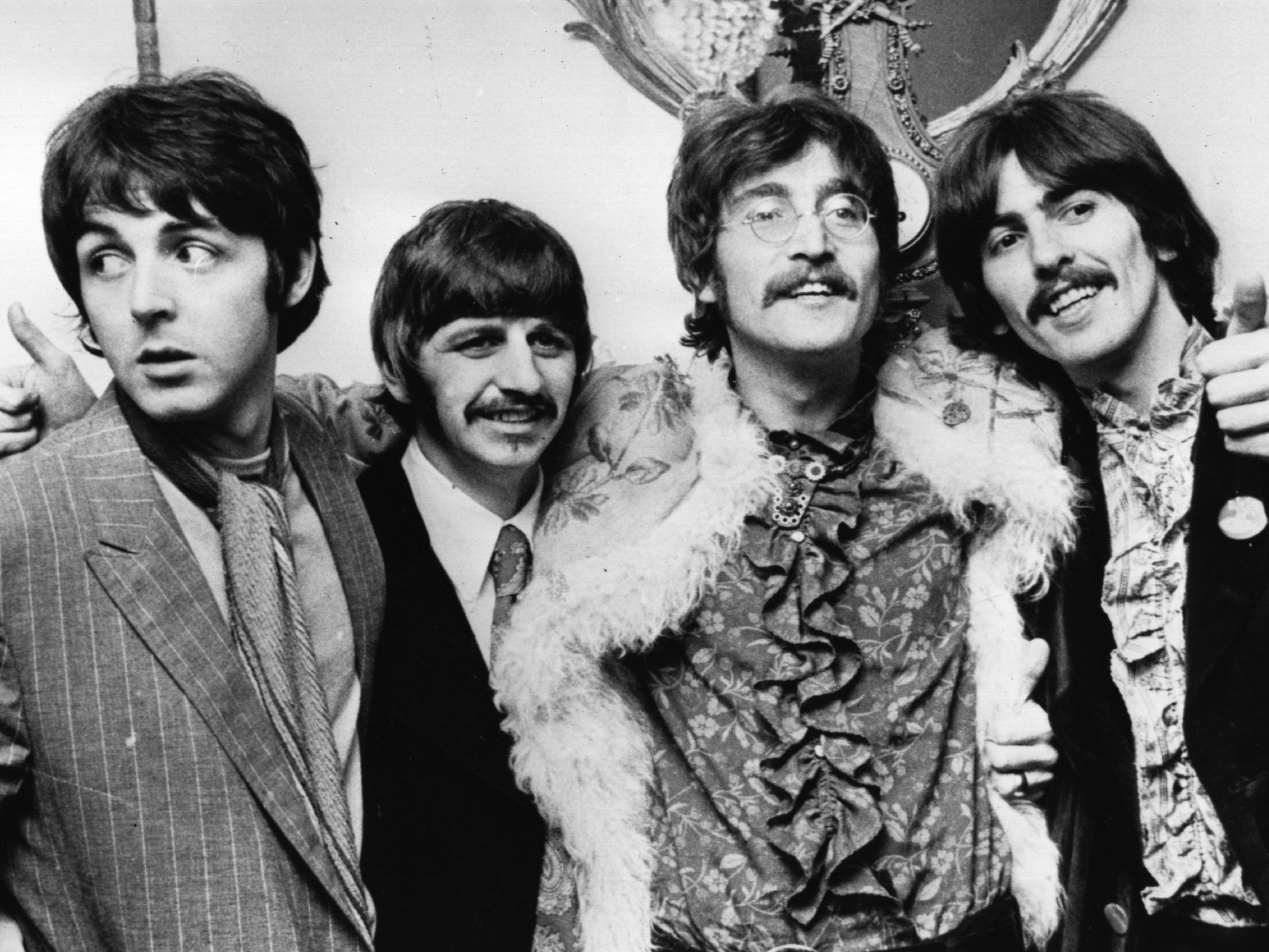

Apparently he is fashionable again, and we commented: “Paul McCartney didn’t used to be cool.” It is a curious grammatical construction, when you think about it, but I think Paul Edwards is right to say that it should be “didn’t use to be cool”. It is complicated by not being able to hear the difference in speech: you would say that McCartney “used to be cool” or that he “used not to be cool”, but a “did” or “didn’t” changes it, as in: “Did you use to listen to the Beatles?”

Spotted on the hard shoulder: In an article about the dangers of smart motorways we had the phrase “twice as likely than”. We meant “twice as likely as”. Thanks to Richard Thomas, who is as sharp-eyed than an eagle, for pointing this out.

Degrees of bad: In an editorial on the vexed implications of Brexit for Northern Ireland, we said: “A border down the Irish Sea remains the least worst solution.” As Roger Thetford reminded us, “least worst” is a common enough phrase, probably because of the assonance, but it makes no sense. We meant “least bad”.

The same article said: “The chances of a UK-US free trade deal will be setback even further if the White House considers that the British government is playing games.” A “setback” is a noun, and is written as one word, but to “set something back” is a verb, and is two words. I don’t know whether there is a rule to it or not, but in the verb form it is possible to stick another word in the middle. We could have said the chances would be “set further back” or “set right back”, so it should not be a single word.

Academic jargon: In a report of the Queen’s Speech debate in parliament, we said: “Shadow business secretary Jonathan Reynolds also critiqued the government’s strategy.” This is a fancy-pants way of saying “criticised”. It is bad enough when academics do it, and we should try to show them an example, not copy them. Thanks to Nigel Fox for criticising us on that point.

Muskets at the ready: We use “spark” to mean start, prompt or trigger too often. In recent days we said that the local election results “sparked a debate”; that food price rises were “sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine” and that an attack in a park “sparks police appeal”. I was going to add the Interpol president’s visit to Paris, which “sparked a backlash”, to the list and suggest that it was not just a cliche but a mixed metaphor, but I am not so sure. Perhaps the analogy is with a flintlock, in which a spark lights the gunpowder, the bullet is fired and the gun recoils. Well, it is a theory, isn’t it?

Eye-shutter: Some Americanisms are fine and vivid expressions, and “shutter” as a verb conveys an image of a shop with its shutters down. But we have had our fun, and it is overdone now. Last week we said the Taliban had allowed some girls’ schools to reopen in Afghanistan, “but kept many shuttered”, and that McDonald’s “announced that it will shutter all 850 restaurants in Russia”. The word has become simply an overlong version of “shut”. Time to shutter it down.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments