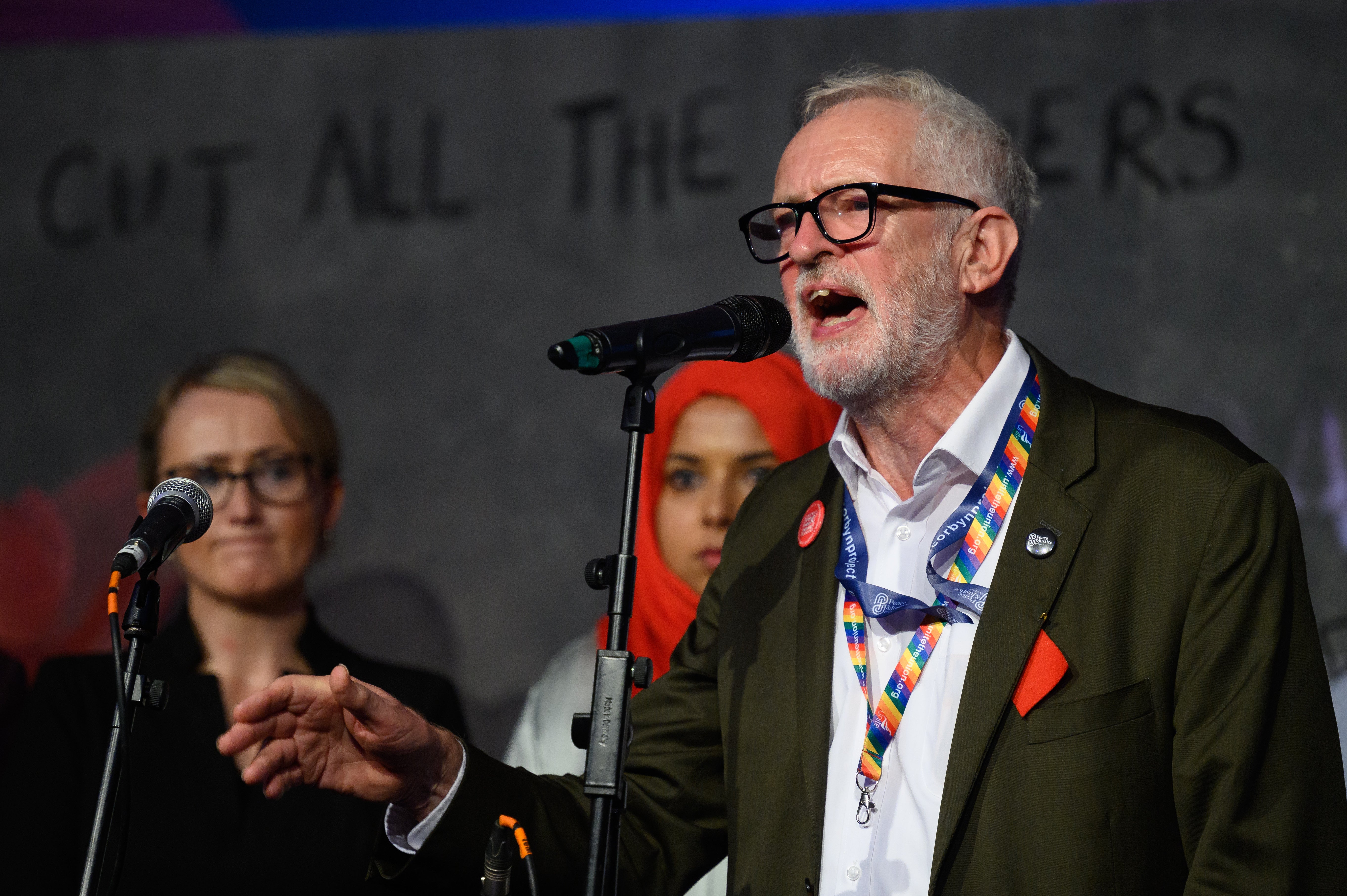

Corbynites fume at Starmer’s betrayal, but will voters think his change is sincere?

One by one, supporters of the former leader have marginalised themselves, writes John Rentoul

The Corbynites are furious that Keir Starmer has betrayed them. In Starmer’s early days as leader, John McDonnell, who was Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow chancellor and chief ideologue, set out the strategy. Starmer had been elected on a Corbynite policy platform, he said, by party members who had mostly voted for Corbyn in the past. He advised that Momentum, the Corbyn supporters’ faction, ought to remain involved at all levels of the party, to hold the new leader to his promises.

That strategy lies in ruins. Not primarily because Starmer betrayed some of the people who elected him, although he has finally broken with them this week in Brighton, but because Corbynites abdicated and left the field clear for their rivals to take the party back.

One by one, Corbynites in shadow ministerial positions excluded themselves by resigning or by putting themselves in a position where Starmer had no choice but to sack them. Rebecca Long-Bailey breached the policy of zero tolerance of antisemitism last year. Corbyn himself put himself outside the parliamentary Labour Party by refusing to accept the findings of the statutory Equality and Human Rights Commission. This week Andy McDonald resigned from the shadow cabinet over the demand for a £15-an-hour minimum wage, which is wishful thinking rather than serious policy.

At the same time, Starmer tightened his grip on the party’s national executive because the bakers’ union was replaced by the musicians’ union (“drum roll, please,” as Andy Ibbs said on Twitter). The bakers immediately announced that they would be disaffiliating from the party, so that was another Starmer gain.

The leadership won the votes that mattered. The most important one, on the rule changes designed to keep the Corbynites out of power in the party, was carried at the start of the conference by just 54 per cent to 46 per cent, but from that all else flows. Some motions that the leadership regards as “unserious” were carried, such as the one condemning the Aukus security pact and the one supporting a £15 minimum wage, but they are not binding. The significant fact of the conference is that Momentum’s boast that it spoke for a majority of the delegates from local parties turned out to be unfounded, and that Starmer now has firm control of the party machine at all levels.

Nobody could be sure until the actual people turned up at the seaside, but the annual conference, the party’s sovereign body, which was controlled by the Corbynites, is now securely loyal to the new management.

However, that still leaves one big problem for Starmer unresolved. One of the most telling lines in his speech was this, in a section addressed to the voters whom Labour failed to persuade last time: “We will never under my leadership go into an election with a manifesto that is not a serious plan for government.”

That sounds good. He and Rachel Reeves, his shadow chancellor, have made some progress in restoring Labour’s reputation for prudent management of the public finances by avoiding spending promises and pushing the line that they would treat taxpayers’ money as if it were their own. That is in sharp contrast to the huge spending plans in the 2019 Labour manifesto that were supposedly paid for by tax rises on companies that would never have materialised. Then, just as the election campaign began, Corbyn and McDonnell added a huge unfunded commitment to women’s pensions.

The problem for Starmer is that he was a member of Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. He asked the British people to vote for something that he now accepts was “not a serious plan for government”. That was less than two years ago. Why should the voters believe someone who said he was against fiscal responsibility before he was for it?

It is the same with much of the rest of the Corbyn programme. Boris Johnson had fun in the House of Commons the other day when Starmer praised Nato and stressed Labour’s undying commitment to the Atlantic alliance – Johnson pointed out that the Labour leader had only recently asked the British people to elect as prime minister someone who does not believe in Nato or the nuclear deterrent.

These issues are not as sharp as they were 30 years ago, when Neil Kinnock, having advocated British nuclear disarmament, switched to saying that he would keep our nukes as long as other countries kept theirs. But there is a similar problem of explaining an opposition leader’s true beliefs to a sceptical electorate.

The Corbynites may have marginalised themselves, but Starmer still has to explain to the nation why he went along with them for so long.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments