Should British spies have a ‘licence to kill’? The late John le Carre would have enjoyed this debate

The news that MI6 may be committing crimes in the UK is worthy material for a spy novel, says Mary Dejevsky. More importantly, it raises the question of whether our secret services need more or less oversight

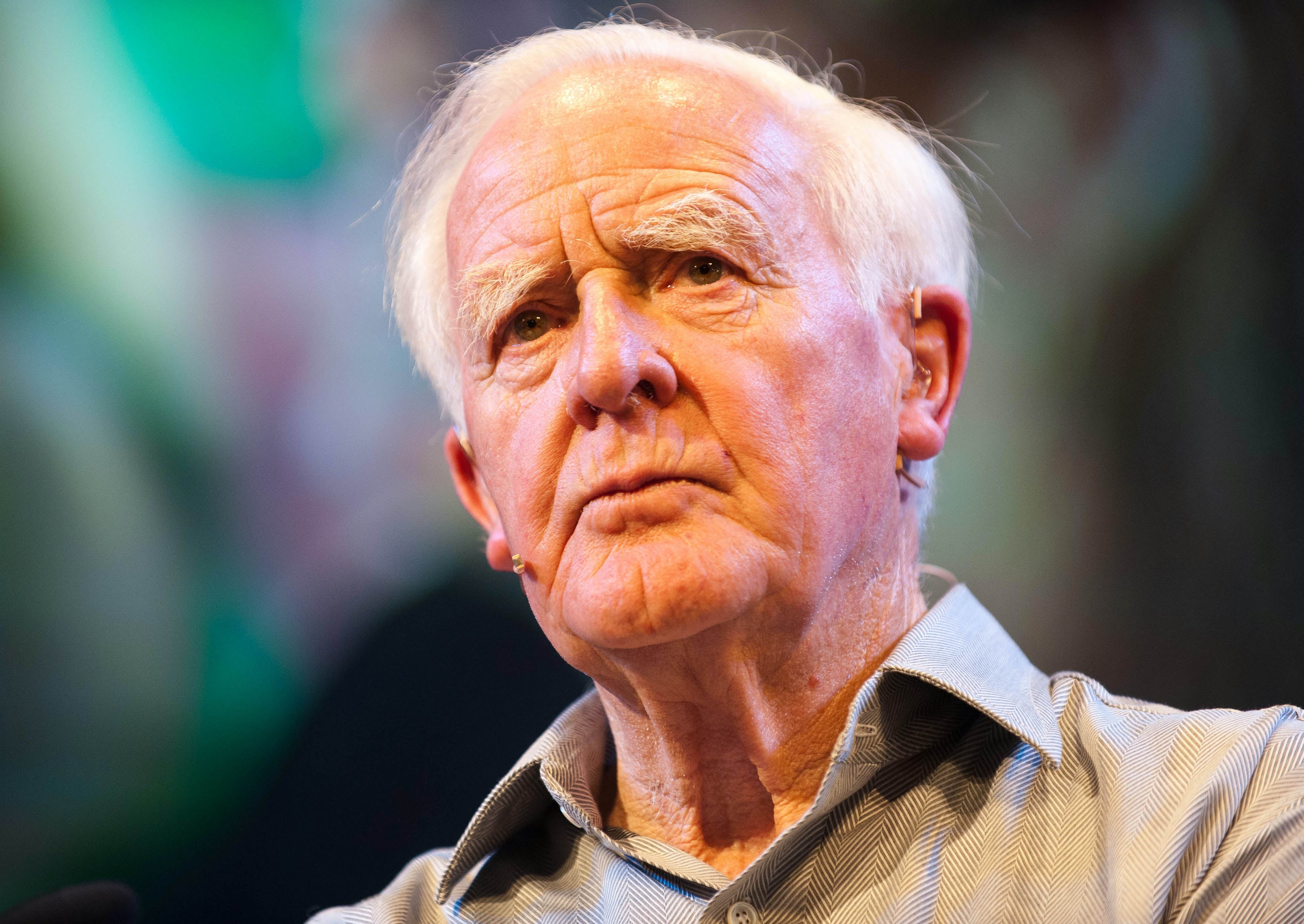

John le Carre, the writer whose fiction illuminated the ambiguities of espionage and treachery more than any factual accounts could ever do, died last weekend at the age of 89. And he would surely have savoured the irony. The timing was such that appreciative obituaries and warm personal memoirs found themselves sharing media space with some of the more tantalising glimpses afforded to the British public in recent years of the often uneasy relationship between spies and the law.

One of these, worthy of a Le Carre novel on its own, was the revelation that MI6 had been rapped over the knuckles by the official watchdog for not giving the foreign secretary information about a potential, or proven, “rogue” agent. Under the law, the foreign secretary is in charge of both MI6 (officially SIS) and the intelligence-gathering agency, GCHQ, and must sign off on anything that might put an agent on the wrong side of the law. A section of the Intelligence Services Act (1994), dubbed the “James Bond clause”, or “licence to kill”, exempts British agents operating abroad from prosecution in the UK, so long as they have the foreign secretary’s authorisation for whatever they were doing.

In this case, it appears, from the report of the watchdog, the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office, the foreign secretary was asked to sign off on the retention of this particular agent, without being told that he was considered “high-risk” – a term that could cover criminal activity, up to and including killing. The lack of this information effectively severed the line of judicial, let alone moral, accountability. In effect, MI6 was effectively circumventing the flimsy government oversight that currently exists.

Consider, too, what we have still not been told. We have the principle, but not the facts. Who was the foreign secretary at the time? If this refers to last year, which appears to be the case, it could be either Jeremy Hunt or Dominic Raab. We don’t know. We don’t know which country the agent was or is operating in. We don’t know his – or her – nationality. We don’t know what he/she was getting up to. All that has been revealed is that MI6 failed to comply with the regulations in place – which leaves the agency in effect a law unto itself. In this one instance, yes – but were there more?

Apparently, so, because the very next day a hitherto secret judgment was made public (in summary) that seemed to confirm the somewhat cavalier attitude of MI6 and GCHQ to the law. The ruling came from the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, which hears complaints about government surveillance and the like, usually behind closed doors. This case was, if anything, worse, because it appeared to show that the two intelligence agencies had authorised their informants to “participate in criminal activity” in the UK; the so-called “James Bond clause” applies only to operations abroad.

How you feel about these two revelations will probably determine your response to what comes next. Are you shocked that the UK – as a long-time evangelist for the “rule of law”, at least until the Internal Market Bill retained the (now withdrawn) right to break a treaty – has intelligence services that, in some instances at least, disregard the legal constraints decreed by parliament? Or are you perhaps – as, I admit, I tend to be – somewhat ambivalent, even cynical, in the Le Carre mode, about the whole shadowy world of intelligence, where it might seem pretty much anything goes – until, that is, someone gets embarrassingly rumbled (the UK spy’s dead-letter box concealed in artificial stones in a Moscow park), “disappeared” or, in extreme cases, killed.

Is it, in fact, a contradiction in terms to talk about law-governed intelligence agencies at all? Are legal constraints just a cover, adopted by democratic countries, in an effort to make activities seem acceptable that are not acceptable at all? Should we commend parliament for trying, while conceding that, actually, where national security is at stake – or (which is not necessarily the same) our agencies say it is at stake – they should be given free rein to do what only they can do?

As I say, which side you are on will probably determine what you think about a bill that is currently reaching its final stages in parliament. Entitled the “Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Bill”, it essentially makes the “James Bond clause” explicit in law and extends the protection to operations carried out in the UK. Part of the thinking behind it seems to be to plug a gap that, in theory, exposes agents working for the UK to prosecution.

As such, it appears designed to plug particular gaps. One of these might apply to those “informants” referred to in the Investigatory Powers Tribunal’s judgment, who might be “participating in criminal activities” in the UK. Might it – unlike UK legislation generally – apply in retrospect? Could we be looking here at blanket dispensation for some of the UK government’s more despicable actions during the Northern Ireland “Troubles”? Last month, ministers rejected again a new plea for a public inquiry into the 1989 killing of the Belfast lawyer, Pat Finucane. Might we also be looking at cover for agents or officers called to testify in court or at public inquiries? Could this make it possible for intelligence officers, or undercover agents, to provide crucial information to a court that only they might have? And, if so, would such protection be used?

Time and again, a trial never happens or fails, or an inquiry concludes without anything like the full information, because there is a UK intelligence angle. Sometimes this can emerge only at a relatively late stage – and helps to explain why a case has stuttered along with mysterious delays and gaps. A few years ago, I followed a corruption case brought against a Russian-born UK national working at the European Bank for Resettlement and Development (EBRD) that had taken nearly a decade to reach court. When the trial finally happened, the defendant said that he had been approached with a deal by UK intelligence, but had refused.

This case, though, was a mere trifle compared with many others. A whole series of cases connected with the so-called rendition of UK residents or citizens to “black sites” or to US custody in Guantanamo Bay has come to nothing because intelligence officers have not been allowed to give evidence. Successive governments have generally preferred to pay compensation than have such cases come to court.

The case of the Libyan dissident, Abdel Hakim Belhaj and his wife, who were rendered and tortured, following a UK intelligence tip-off to the CIA is one of the most heinous to have come to light. Some 14 years later, they received a full apology from the then prime minister, Theresa May. But no one has ever been held to account. You might also have thought that the Manchester bombing inquiry might want to know how, as political exiles, the bomber Salman Abedi and his family were able to travel to and from the UK to Libya, and how he, on at least one occasion, appears to have been rescued by UK forces. A UK intelligence angle means that this is evidence the inquiry will not hear.

At the belated inquiry into the death of Aleksander Litvinenko, intelligence evidence was heard only by the judge and never saw the light of day. What price the conclusions of such an inquiry? The only partial exception was the inquest into the London 7/7 bombings, where Lady Justice Hallett, managed to have some intelligence evidence given anonymously, from behind a curtain. But this was an exception – and it should not be.

Far from making the intelligence services more accountable, however, we will soon have a law on the books that expressly permits agents to commit crimes – but, of course, only in the name of national security and the greater good. You might argue that it is better to have constraints framed by law than to have no constraints at all. Maybe; but I wonder how far intelligence and the law can ever really live together. Then again, perhaps I have read too much Le Carre.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments