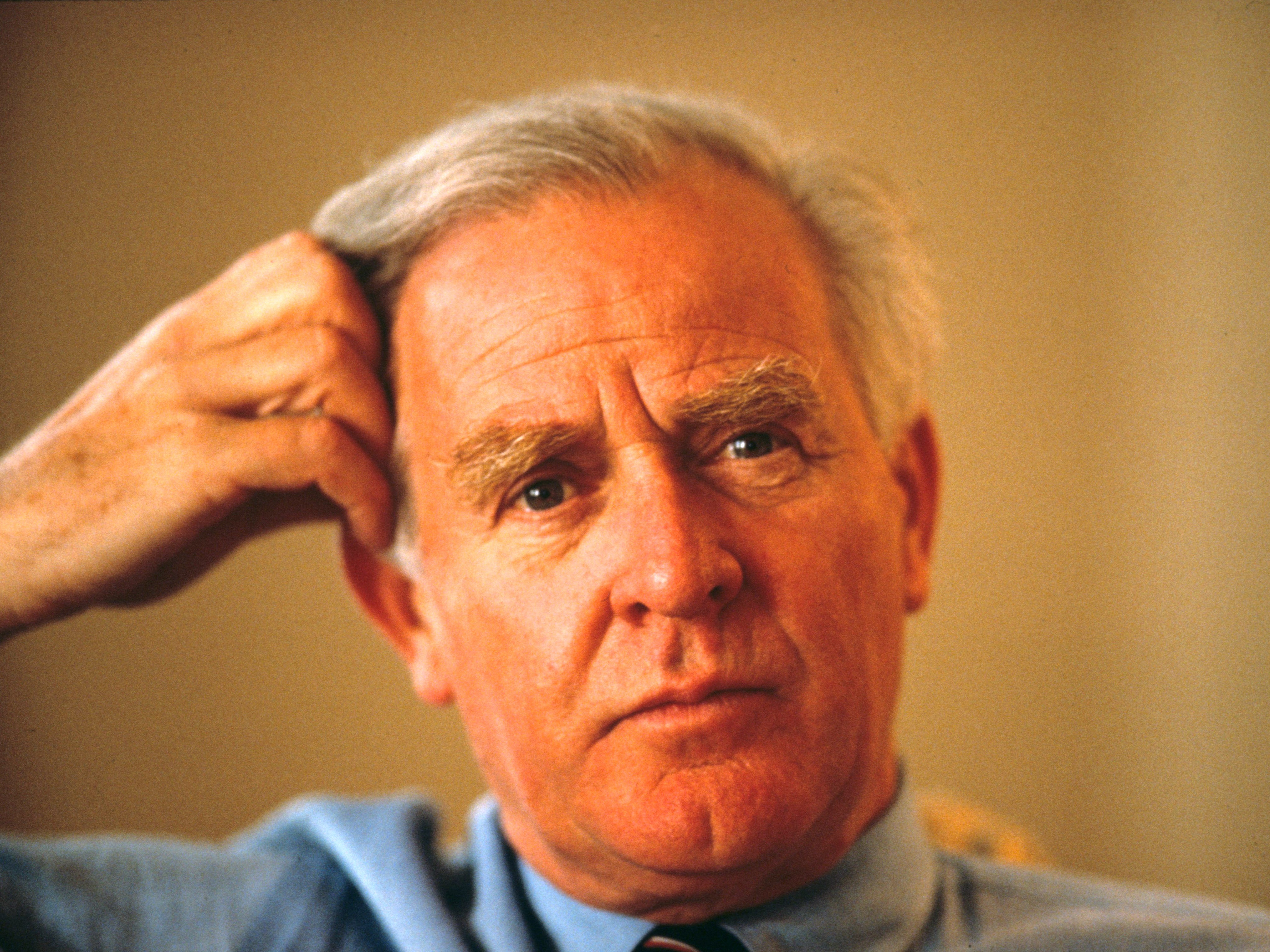

John le Carré: Novelist who turned espionage thrillers into an art form

‘The Spy Who Came in from the Cold’ and George Smiley were his great creations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The author John le Carré, who has died aged 89, transformed the spy novel into a literary masterpiece with complex plots, high tension and realistic dialogue.

He took to espionage thrillers his experiences as an intelligence officer interviewing defectors from the other side of the Iron Curtain in the early days of the Cold War and later work for MI5 and MI6.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, published in 1963, was his first success, an international bestseller turned into a film two years later.

Richard Burton played disillusioned spy Alec Leamas being betrayed by his masters after being sent to East Germany to feign his defection in a story laying bare the lack of morals on both sides of the newly constructed Berlin Wall.

The novel benefited from appearing at a time when readers’ imaginations were fired by the unmasking of Kim Philby as one of the so-called Cambridge Spy Ring – Soviet double agents in Britain.

The public and critical acclaim for The Spy Who Came in from the Cold enabled the author to leave his own intelligence services job in 1964.

Le Carré’s fallible, shabby characters, seedy settings and questioning of the country’s intelligence organisations’ activities contrasted with his contemporary Ian Fleming’s James Bond, whom he regarded as a “consumer goods hero” wearing tailored suits and chasing women.

He described his best-known protagonist, George Smiley, as middle-aged, short, overweight, balding and “dressed like a bookie”.

Following appearances in four of Le Carré’s early novels, Smiley was featured most famously in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), called out of enforced retirement to root out a Soviet mole in British intelligence.

Arthur Hopcraft adapted the book for a seven-part TV drama in 1979 starring Alec Guinness, which proved compulsive viewing. One critic observed that it “killed off the popular image of the spy as James Bond once and for all” and cleverly recreated mannerisms from the novel such as Smiley cleaning his glasses on his tie. It was later made by Hollywood as a 2011 feature film starring Gary Oldman.

The “Karla Trilogy” – named after Smiley’s Moscow counterpart and nemesis – continued with The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), when the MI6 spymaster fends off his government’s threat to dismantle the intelligence service.

Then came Smiley’s People (1979), with him called out of retirement again to investigate the death of one of his former agents before greeting Karla at the Berlin Wall after blackmailing him into defecting.

Le Carré and John Hopkins adapted this third in the trilogy for a 1982 TV series that again featured Patrick Stewart as Karla.

Nine years later, the author brought Smiley back to the small screen for his own adaptation of his second novel, A Murder of Quality, published in 1962. Denholm Elliott played the retired spy boss discovering that blackmail was the motive after being asked by his former wartime secretary to investigate a killing.

Le Carré regarded his 1965 novel The Looking Glass War as the most realistic in describing the tangled web in which he himself had worked – and as the reason for its lack of success.

Many critics regarded his best work to be A Perfect Spy, a semi-autobiographical 1986 novel featuring Magnus Pym – played by Peter Egan in a TV adaptation the following year – as the double agent haunted by memories of his charismatic con-artist father, Rick.

“Writing A Perfect Spy is probably what a very wise shrink would have advised me to do,” the author said.

Le Carré was born David John Moore Cornwell in 1931 in Poole, Dorset, to Olive (née Glassey), known as Wiggly, and Ronnie Cornwell, the inspiration for Rick.

After David’s mother left when he was five, his father was protective of him and his older brother, Tony, to the point of obsession, searching their rooms, monitoring their every movement, opening their mail and listening to phone calls – giving them an apprenticeship on the receiving end of surveillance.

Ronnie, who told his sons that their mother had died, was jailed several times for fraud. Later, he was made bankrupt.

David attended Sherborne School before studying German at Bern University, Switzerland, which led him to interrogate Czech refugees when he was stationed in Austria during national service in the British army’s Intelligence Corps.

While reading modern languages at Lincoln College, Oxford (1952-56), he compiled dossiers for MI5 on activities by suspected left-wing fellow students, before teaching at Eton (1956-58).

He joined MI5 in 1958 and, two years later, transferred to MI6 as an intelligence officer in the guise of second secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn, then a political consul in Hamburg.

When he wrote his first novel, Call for the Dead (1961), with Smiley investigating the apparent suicide of a suspected communist, he adopted the pseudonym John le Carré because of a rule forbidding intelligence employees to write under their own names.

Smiley later featured in The Russia House (1989), The Secret Pilgrim (1990) and A Legacy of Spies (2017).

Le Carré’s other thrillers included The Little Drummer Girl (1983) and, tackling global intelligence issues in a post-Cold War world, The Tailor of Panama (1996) and The Constant Gardener (2001).

A Delicate Truth (2013), speculated by some to be based on the 1988 SAS killing of unarmed IRA members in Gibraltar, signalled Le Carré’s transformation from believing that the intelligence services were ultimately protecting people’s liberties to being disillusioned with misuses of power.

His 2016 memoir The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life contained reflections on the lack of affection he received as a child and random recollections about a parrot mimicking machine-gun fire in a Beirut hotel, and New Year’s Eve celebrations with Yasser Arafat.

Le Carré’s first marriage, to Ann Sharp (1954-71), ended in divorce. He is survived by his second wife, Jane Eustace, whom he married in 1972; their son Nicholas (author Nick Harkaway); Simon, Stephen and Timothy, the children of his first marriage; and his half-sister, actor Charlotte Cornwell. His half-brother, Independent journalist Rupert Cornwell, died in 2017.

John le Carré, writer, born 19 October 1931, died 12 December 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments