What we can learn about relationships from Joe Biden and Xi Jinping

It might just be the best model for the relationship between the world’s largest and second-largest economies for the next decade and more, writes Hamish McRae

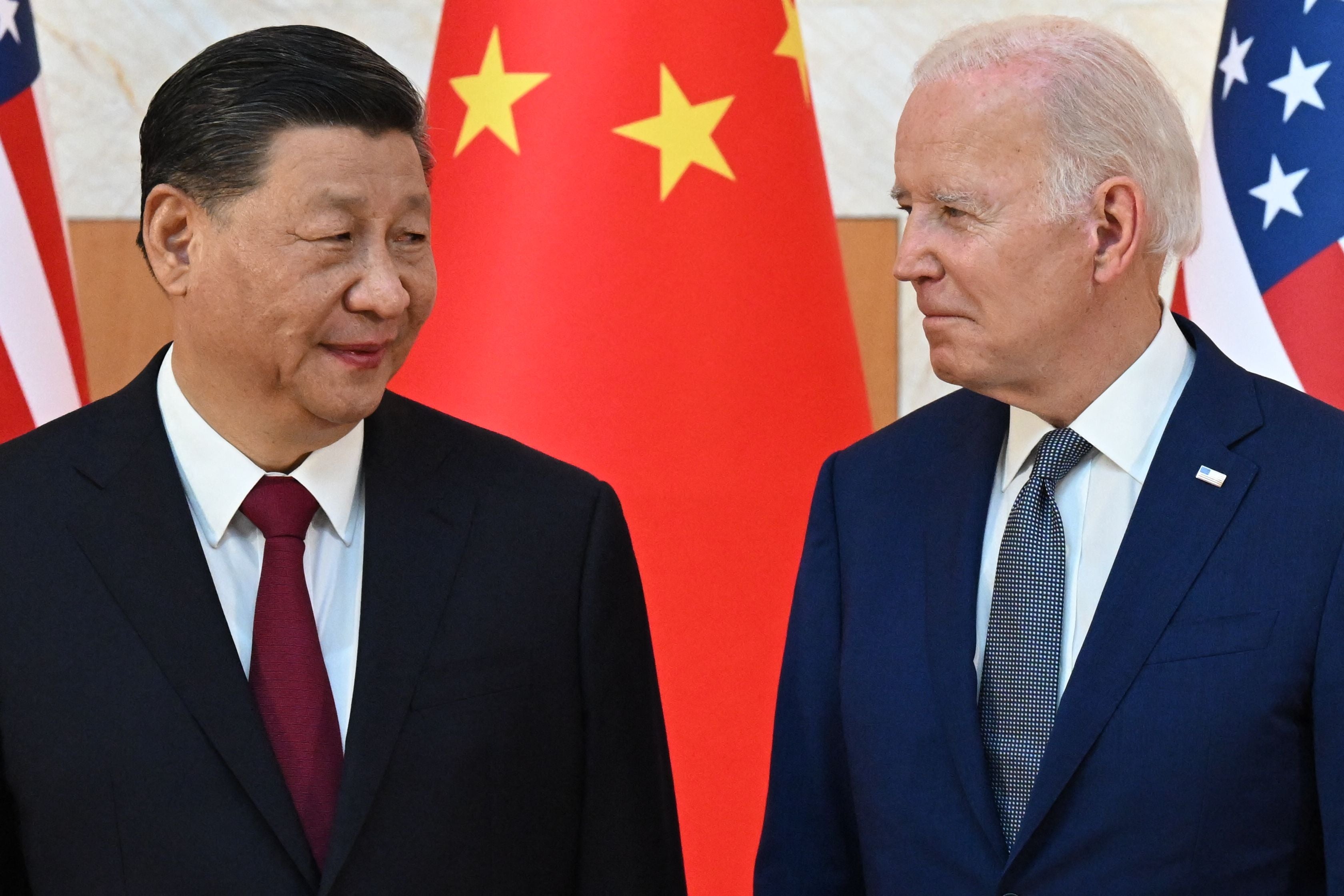

It will be a new cool war, not a repeat of the Cold War of the 1945-1990 period. Viewed from here in Washington DC, the workmanlike relationship between President Biden and President Xi – who met in Bali ahead of the G20 summit – is the best model for the relationship between the world’s largest and second-largest economies for the next decade and more.

In areas where it is in their mutual self-interest, such as combatting the climate crisis, they will cooperate. In areas where it is not, they will compete. Both accept that the world economy is splitting into two areas of influence, and that is where the battle for dominance will be. But this battle will stop short of an economic war on the scale of the one now being led by the US against Russia. Each has too much at stake.

For people who bought the notion, popular a few years ago, that national boundaries will fade and the world will be run by political and business elites – extreme globalisation – this is one more nail in the coffin.

Remember the idea of “Davos man”, shorthand for that elites view of the world, exemplified by the grandees who met every year at the Swiss ski resort of Davos? It shut down after the pandemic stuck but was revived in cutback form in May this year, with Sam Bankman-Fried among the headlined speakers. (A couple of weeks earlier, he had shared a platform in the Bahamas with two Davos alumni, Tony Blair and Bill Clinton.)

Well, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ended any lingering notion that globalisation could career on as before, it was clear that globalisation was in retreat. Donald Trump’s trade offensive against China was a big step in that direction. Then the pandemic hit, disrupting global trade and forcing companies to try to make their supply chains more robust.

Words such as “re-shoring” and “near-shoring” replaced off-shoring. Russia became uninvestable, with multinationals scrambling to get rid of their businesses there and having to face that their investments were pretty much worthless. Then, as we have seen so brutally in recent days, the crypto crash has shown the limits of globalisation as far as currencies are concerned.

So what’s next? The fear that emerging economies might have to choose between the US and China was greatly increased by the move last month by the Biden administration to limit access by China to high-tech semiconductors, together with subsequent warnings of further restrictions.

China can build that expertise, but this will take time. If the US can continue to race ahead, China will always be playing catch-up, as Russia found it had to do during the Cold War, when it had no access to US computer technology.

In the past few days, there have been two important signals from the US regarding its economic policy towards China. One was a speech by treasury secretary Janet Yellen last Friday, in which she said that the US was not seeking to “paralyse China’s economy and stop its development”. The other was this Biden/Xi meeting.

This is really important. It is for the political commentators to interpret what the meeting means for issues such as cooperation against climate change and the stand-off over Taiwan, but from an economic perspective what matters is the extent to which the present close commercial relationship between the two countries will remain intact. The US may not be wanting to stop China’s economic development but it will do its utmost to stop China’s current relatively open access to American technology.

If you are an American multinational you may face a dilemma. Not only China is a huge market, for example, the second-biggest for Tesla, but it is totally integrated into the US supply chains. Some 90 per cent of Apple products are made in China. In a “Davos man” view of the world that’s fine. Why let politics get in the way of business?

But if producing stuff in China means transferring top-end US technology, that is not going to be fine at all. If the unthinkable were to happen and China invaded Taiwan, maybe trade would not stop overnight but the country would be closed to any further US investment. Already Apple is starting to make iPhones in India, though the build-up will take many years.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The midterm elections have given the Biden administration a new self-confidence and, as far as China is concerned, a new authority. It is dealing with an American president who, for all the difficulties he is facing, has been given more support by the voters than he might have expected.

China has two years to rebuild a decent working relationship – as indeed the two presidents had years ago in their previous roles – that will stop short of a cold war. There will be economic costs in a cool war.

The vision of ever-greater globalisation of the world economy is indeed dead. Rivalry will increase. But it is less likely to be destructive now than it might have been a few days ago. And that is good news for the rest of the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments