The pretence of the government’s preparedness over coronavirus won’t work for much longer

Editorial: The response to under-delivering has been simply to make bigger promises. People were receptive initially, but they won’t be if things continue like this

The public, by and large, has given the government the benefit of the doubt over its handling of the coronavirus epidemic, but if the UK does go on to have the worst outbreak in Europe, as one leading expert has warned, and if nurses continue to die for lack of proper equipment, it is questionable how long that will last.

Professor Jeremy Farrar, who is director of the Wellcome Trust and a pandemics expert on the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), which has been advising the government throughout this crisis, told the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show: “The UK is likely to be certainly one of the worst, if not the worst, affected country in Europe.”

As so many others have done, Mr Farrar compared the UK with Germany, who he said “very early on introduced testing on a scale that was remarkable and continued to do that and isolate individuals and look after those who got very sick”.

Comparisons between countries are easy to make and not always entirely illuminating. For all the now ubiquitous graphs that track the growth of death and infection rates between China, Italy, Spain, the US, South Korea and everywhere else, the fundamental data points – the nations themselves – are not the same.

The UK has Europe’s only real megacity. The US’s outbreak is still largely the story of New York. Even now, the devastating impact of coronavirus on Italy has devastated only one of its regions.

China is a huge country, Wuhan is as large as London, but it was itself quickly and aggressively quarantined from the wider nation.

Germany happens to be the home of the world-leading diagnostics industry which it was quickly able to utilise (and UK politicians should have been quicker to be more honest about the fact that we are not).

Chinese authoritarianism has proved curiously useful in controlling the virus, though there are legitimate questions about whether it has been entirely honest in reporting the scale of its outbreak to the wider world.

If coronavirus reaps a deadlier whirlwind on the UK than in vaguely comparable European countries, the blame will be attached to the slowness at which lockdown restrictions were introduced, particularly when the effects of not acting were clear to see elsewhere. But even the government’s own scientific advisers couldn’t agree on the best way forward. And the steps taken to place the economy on temporary life-support would have been far less effective if introduced after lockdown, when hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of now furloughed staff might have been made redundant instead.

Even now, we are led to believe that Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, is stressing in meetings the immense risks to public health of a continued lockdown and its terrible economic consequences.

The government continues to tell us to “Stay at Home, Save Lives”, but privately senior figures appear to be admitting they did not foresee the people taking the lockdown so seriously. They thought that one in five children might remain in school, for example. That has not happened. The furlough scheme has been taken up by millions more people than expected.

They stress, in other words, the importance of a lockdown they imagined, hoped even, would be less severe.

Arguably, the constant country-by-country comparisons of a public health emergency may lead to a widening of the debate around the NHS. Traditionally, the service is venerated by those who wish to venerate it, by comparing it with the worst of the US system, and then the argument is considered over. But this crisis has made clear that the French, the Italians and the Germans all offer, for the most part, superior quality healthcare to our own.

The NHS, for all its wondrous advantages, is a system that has not been copied by any major country. The scale of German testing, to take but one example, owes much to its decentralised, industry-backed system. Here, we have struggled to link up public and private at the speed and scale required.

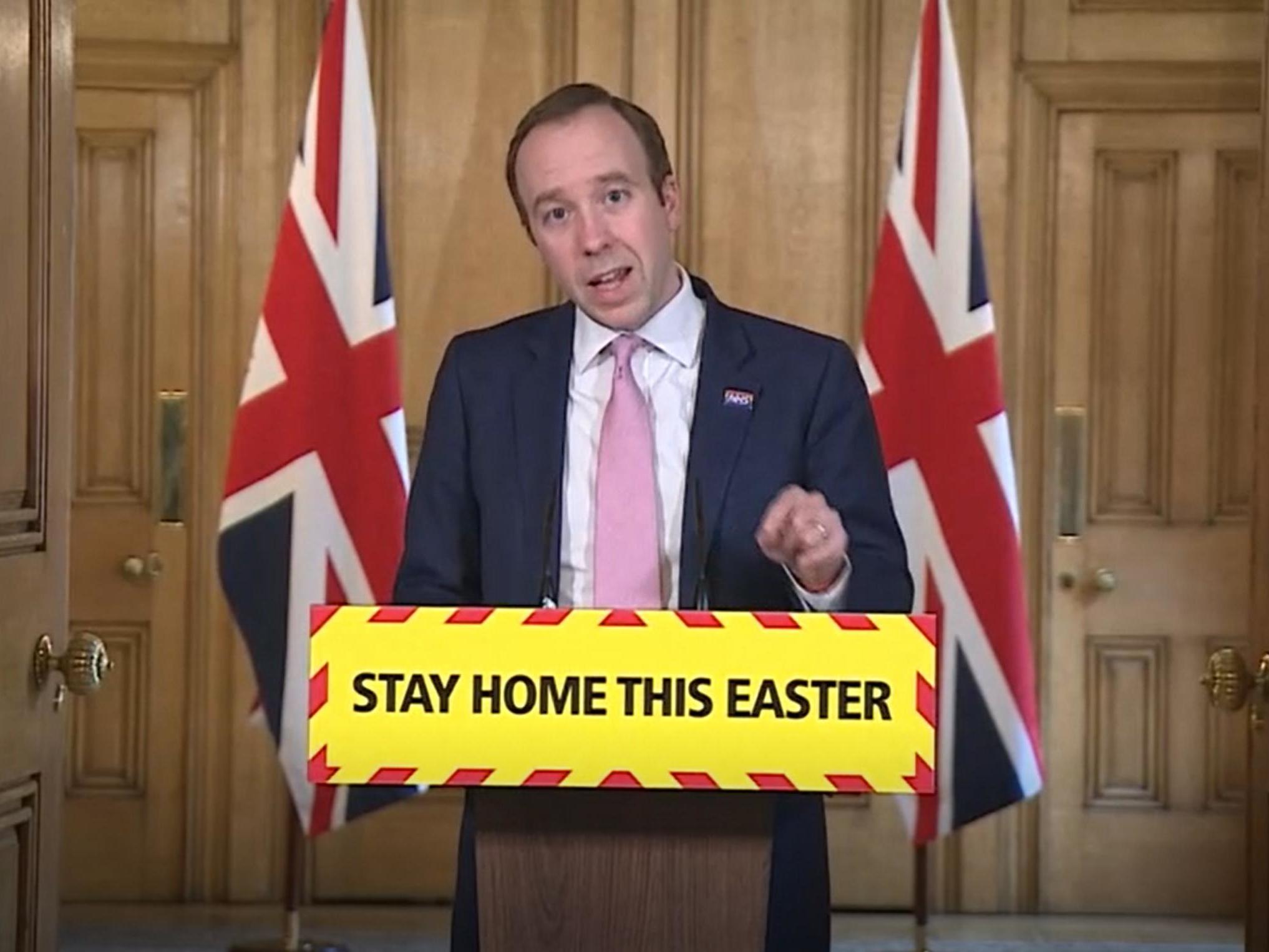

The response to under-delivering has been simply to make bigger promises. The testing issue briefly went away when Matt Hancock promised to get to 100,000 tests a day by the end of April. It is far from clear how he will meet that target.

The failure, or refusal, to even dial into various EU conference calls on ventilator procurement is an outrage.

Nurses have now been advised by the Royal College of Nursing to consider refusing to treat Covid-19 patients if they do not have the right equipment. The country is currently in the process of beatifying its healthcare workers. It is being encouraged by its government to do so, and yet that government is simultaneously failing to provide them with the required protective equipment.

In these early, almost novel, weeks, the public has been patient and supportive, but coronavirus is not going away for a long time to come. It may not be long before the mask starts to slip.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments