I was meant to be at Cop26, but India’s justice system denied my civil liberties

I followed the rules but I was subjected to unnecessary court proceedings, criticised and unfairly compared to liquor barons by the police, and I still had my passport withheld, writes Disha Ravi

Standing in the police station in Bengaluru, I listened to the senior police officer berating my mother for raising a rebel who refuses to stay silent. He had plenty of advice on how mothers should raise daughters to follow the system.

After he was done, he shifted focus to me and began to compare me to Vijay Mallya, the liquor baron of India who fled the country to escape INR 9000 crores’ worth of debts. I marvelled inwardly at how he could compare a billionaire to a climate justice activist. He implied that I was applying for a passport because I too wanted to flee, failing to acknowledge that getting a passport and leaving the country are two very different things.

I had never dreamed of leaving India, let alone fleeing the country. This was simply because the zeros at the end of the price of the plane ticket were more zeros than my family made in six months. Even if money hadn’t been an issue, I wanted to stay in my country.

India’s obsession with preserving caste order, ensuring a continuous supply of toxic air, and slapping citizens with sedition charges every time a minister’s vanity was wounded on Twitter, kept me rooted here. The last scenario would keep me here in more ways than I could ever have imagined.

Following my arrest and bail in February 2021, my bail conditions stated that I was not allowed to leave the country for the duration of my proceedings. Being on bail in India means that you are only partly free. Your case is a scarlet letter that no one can miss; the First Information Report (FIR) number walks with you in all aspects of your life, and it prevented me from going to Cop26 in Glasgow.

I was to attend Cop26 this year in order to report for Grist. To be at Cop26, I would have to pass through two hurdles – one was to get a passport, and the other was to file for an exception with the court that was in charge of my case. My leaving the country would be at the discretion of the court. But I never even got to stage two, because I am still stuck at stage one.

Bail is granted to a person on the presumption of innocence. The court prescribes that the country operate on this assumption, but this order of presumption of innocence doesn’t leave the page it is written on. Applying for a passport was asking for too much. I was expected to be grateful for my “freedom”, for being allowed to exist in my house and in my state. And this is the general expectation from those incarcerated – be grateful for your early bail, be grateful that you are not locked up for your thought crimes. But why should we be grateful?

Why is our idea of freedom limited to not being encased within the physical walls of a prison? The carceral system has forced my freedom, and the freedom of those incarcerated, to be bound to the state at all times. I am outside but I am not free.

Applying to get my passport, having followed all due process, was a reminder of that. The Ministry of External Affairs in India has issued a notice which says that citizens against whom proceedings before a criminal court are pending are entitled to a passport. So, I applied for one. I disclosed details of my pending court proceedings. I followed the rules, but I was subjected to unnecessary court proceedings. I was criticised and unfairly compared to liquor barons by the police, and I still had my passport withheld.

Two court hearings, 60 days (more by the time this is published), two police visits, and two passport office visits for a passport that isn’t here yet. In India, it takes around 60 days to grow tomatoes. It takes 60 days for a newborn baby to connect human voices to their respective faces, 60 days for someone to learn the basics of coding, and 60 days for the passport office to come up with a feeble excuse for why they are withholding my passport.

The state offers relief on paper, but crushes people’s grain-sized freedom at every stage. To be an incarcerated person in India is to be denied civil liberties. You cannot get a job, you cannot get a basic document, and your loyalty to the country will always be questioned and punished. Carceral systems such as prison, policing, and imprisonment are harmful and ineffective responses to crime, which only serve to exacerbate the suffering they purport to address.

The carceral system is also designed to punish marginalised and economically exploited communities. My time in Tihar jail taught me more than I have learnt during the rest of my life. My fellow inmates all had one thing in common: most of them were from economically exploited, Muslim, Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi backgrounds. More importantly, most of them were awaiting trial.

According to 2019 NCRB (National Crime Records Bureau) data, 69 of every 100 prisoners in India are awaiting trial. Of these, 28 will get out in three to six months of incarceration. 14 will spend between one and three years behind bars, despite not having been proved guilty yet. Although Muslims make up only 14.2 per cent of India’s population, they accounted for 16.6 per cent of convicted prisoners, 18.7 per cent of those awaiting trial, and 35.8 per cent of detainees in Indian prisons, as of December 2019.

Dalits made up around 21.7 per cent of convicted inmates, 21 per cent of those awaiting trial, and 18.2 per cent of detainees in Indian prisons. However, they make up only 16.6 per cent of the population. And lastly, indigenous people accounted for 13.6 per cent of those imprisoned in Indian jails, with Scheduled Tribes accounting for 10.5 per cent of those awaiting trial and 5.6 per cent of those detained. Their population constitutes 8.6 per cent of the Indian population.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

According to a study by Delhi-based lawyer Abhinav Sekhri, the lack of clear guidelines identifying which types of offences should allow for arrest without a warrant, or deny the presumption of bail, allows for the simple forfeiture of liberty. Even bail on the presumption of innocence is a symbolic read with a lazy discharge. The truth is that your arrest, and the FIR number that is filed, is a branded scarlet letter that follows you around.

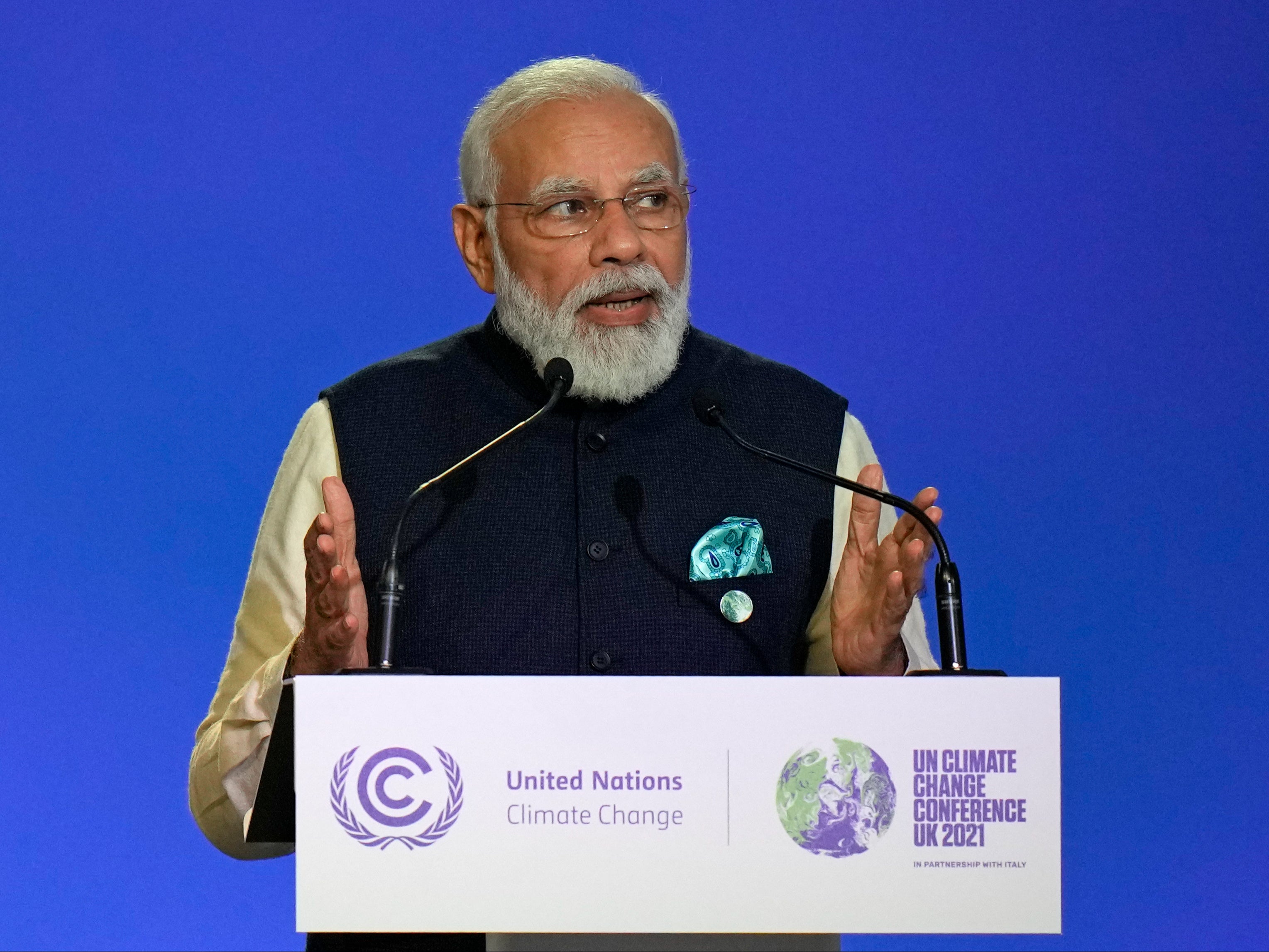

I wanted my passport to attend Cop26 because it was an opportunity to further conversations around the climate crisis and ensure accurate reporting of the severity of the collapse of ecosystems and biodiversity. World leaders have reduced Cop26 to a PR exercise, and I wanted to be there. I deserved to be there.

The denial of my passport led to a denial of my physical presence at Cop26. The denial of my civil liberties is a chunk of the larger problem of the criminal justice system in India. We don’t need reforms to the system, because reforms don’t play out in real life. We need the abolition of the carceral state. The social causes of crime necessitate social solutions, beginning with bettering everyone’s living conditions.

We need equitable access to the planet’s resources, free access to quality education, safe housing, accessible and free healthcare, efforts made to conserve wildlife and ecosystems, and investment in community self-governance. We need better simply because we deserve better.

Disha A Ravi is an Indian climate and environmental activist with Fridays For Future

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments