Biden is acting more like Trump in Russia than you might have thought

An important meeting took place this week that received a fraction of the attention it deserved, writes Mary Dejevsky

An important meeting took place this week that received a fraction of the attention it deserved – and I don’t mean Joe Biden’s damp squib of a “Democracy Summit” that opened in Washington on Wednesday night.

True, the encounter I am talking about took place in the ether rather than in person – as so many have done over the past almost two years. True, partly as a consequence, it was shorn of almost all of the trappings associated with such high-level encounters. And, true, much else was going on, with a juicy political scandal in the UK, a new Covid variant running amok and the transfer of power in Germany. But none of that should detract from its significance.

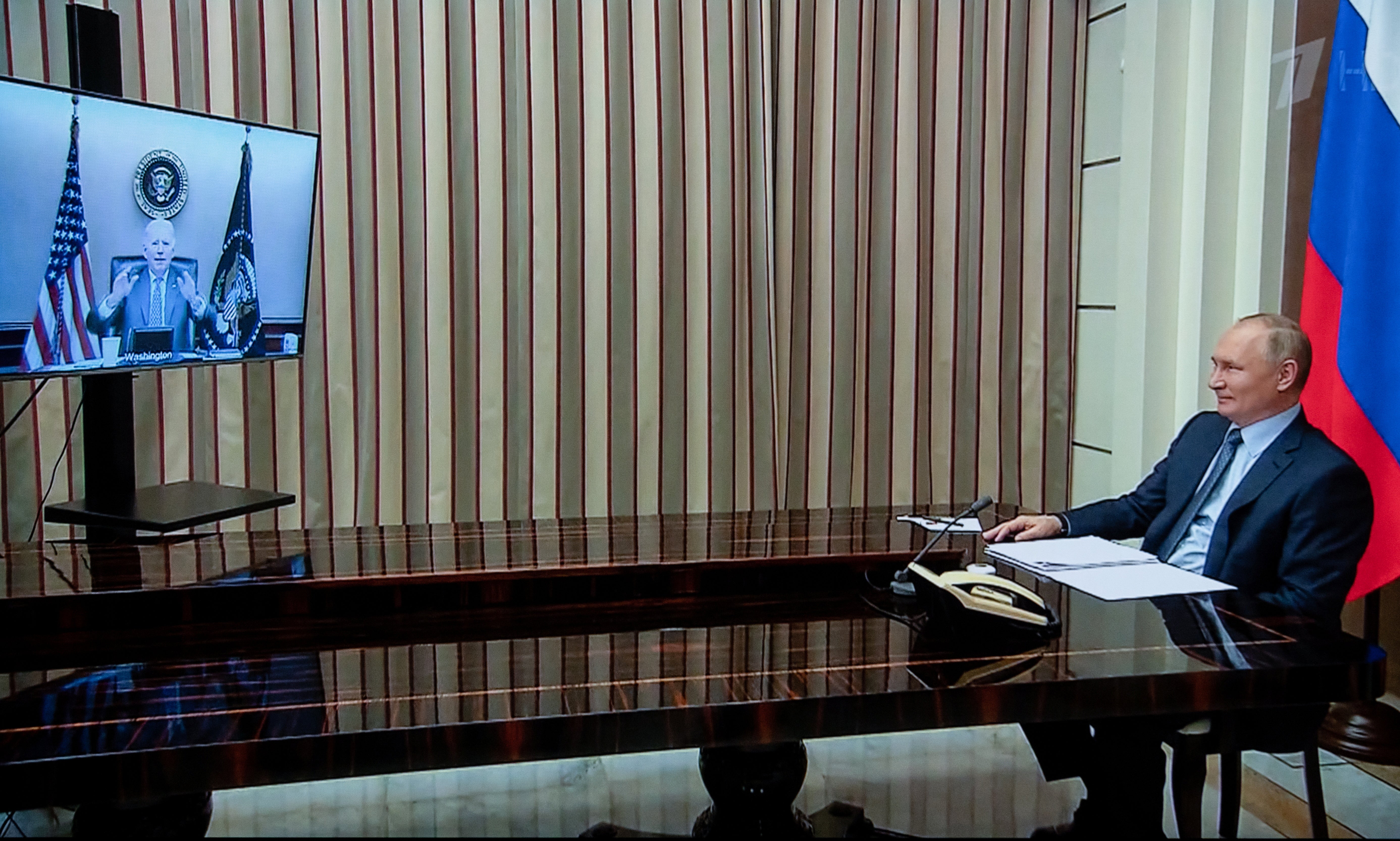

The meeting I am talking about took place on Tuesday morning in Washington, afternoon in Moscow, and entailed two hours of direct talks between President Biden and President Putin in what amounted to a good old-fashioned summit in substance, if not in form. The two leaders had last met face to face in Geneva, in June, in what had been cast very deliberately as a summit in the classic late Cold War mould.

They had gone their separate ways, having opened a channel of communication, but apparently achieved little else. It increasingly transpires that this was not quite true. While the general assessment – heard repeatedly in London and circles in Washington – is that relations are as bad as they have ever been in the 30 years since the Soviet collapse, this is by no means the whole story.

When I was in Sochi for the annual Valdai meeting of Russia watchers, what most surprised me from the long question and answer session with Putin was the generally positive gloss he put on the state of Russia’s relations with the United States and, in particular, with Joe Biden. From Putin personally there was not the slightest air of any new Cold War.

All right, so Putin came across as in a strikingly upbeat mood that day, which was not altogether predictable given the pandemic, the dip in his poll-ratings, and uncertainty surrounding the fate of Russia’s new gas pipeline to Germany, Nord Stream 2. Being nice about the US might simply be seen as part of his overall good mood. But there were specifics.

He enumerated the various working groups that had been set up for Russian and US experts to exchange views, which was a direct spin-off from the Geneva summit and a development he clearly approved of. In other words, there was a great deal of talking going on at a second (and third) tier level behind the scenes, which was a lot more than there had been in the four years before.

Putin also praised Biden’s decision to stand by Donald Trump’s plan to end the US presence in Afghanistan and the fact that the withdrawal had been completed, albeit in something of a chaotic rush. To which you might say, well, of course, Putin would speak well of an episode that showed the US as weak and running away from a region not a million miles from Russia’s backyard.

But that argument only stands if you disregard the very real threat to Russia from any new instability seeping through Central Asia into Russia’s borderlands. And, if you ignore what Putin also said: which was that he respected Joe Biden for the way he had accepted responsibility for the withdrawal and for what had gone wrong.

This said something about Putin’s view of leadership. But it said even more about the establishment of a degree of mutual respect between the two presidents, at least as seen from Moscow. And respect is something that the Kremlin prizes, however lopsided the two countries’ current economic and military strength.

As is well-known, Putin was sorely disappointed with Donald Trump, largely because he had held out the prospect of improved relations, but had grievously failed to deliver – or rather, as I would see it, had his intentions quite unconstitutionally sabotaged by the malicious confection of “Russiagate”. When Trump left office, US relations with Russia were – if anything – worse than they had been when he had entered the White House four years earlier.

After the Geneva summit, however, the only quarrel that routinely came up concerned the number of accredited diplomats in each capital. It has still not been resolved, as was apparent from the Kremlin statement on Putin’s phone-call with Biden.

Given what seemed the improved atmosphere on most other matters, however, it has been unexpected, even shocking, to hear the ever more alarmist warnings emanating from Washington over the past month about an imminent Russian invasion of Ukraine – based, it would appear, on satellite intelligence of troop movements inside Russia.

These warnings soon made their way across the Atlantic, to the UK, to Nato and – of course – to Ukraine, culminating in a warning issued jointly on the eve of the Biden-Putin phone-call by the US, the UK, France and Germany among others of dire consequences, should Russia mount an invasion.

Now, it seems to me for very many reasons, including the sheer folly of a winter war anywhere near that part of Europe, and the likelihood that Ukrainians would fight, precipitating a conflagration that could embrace the whole region, that these warnings are probably just the latest version of the western hawks’ generic Russia threat, which they take out and dust off, whenever it looks as though relations might, perish the thought, take a turn for the better.

But it also suggests to me that there may be new efforts afoot, whether initiated by Moscow, Washington or Kyiv, to try to end the conflict in the east of Ukraine, and that this could have spurred the mobilisation of powerful interests that see the only acceptable outcome as the full integration of Ukraine into the western (that’s to say, Nato) camp.

This interpretation of what is going on seems additionally likely, given that Russia has in the past two weeks – for the first time – explicitly stated that for Ukraine to join Nato would constitute a “red line”.

It is clear from the – rather different – read-outs of the Biden-Putin phone call from the White House and the Kremlin respectively, that Ukraine was discussed. What was also clear, however, was that, while many in the west have been busy stoking fears of a Russian invasion, Moscow has a fear of its own security being threatened by a western military grab for Ukraine.

The dangers stemming from these mirrored fears should be obvious – and may be what gave rise to this “virtual” mini-summit. The result was no meeting of minds, but there was agreement to continue talking at a lower level – which was seen as positive by Moscow, but perilous by some western advocates for Ukraine. More hopefully, the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, who is in the unhappy position of seeing his country, as so often, talked “over” by bigger powers, said he saw it as a good thing that the US and Russia were talking.

It must be hoped that the alarmist talk of a Russian invasion now dies down. Biden and Putin are known to speak regularly on the phone, but this call was deliberately different. It was set up as a “virtual” mini-summit and the civil introductory greetings were live-streamed. It was designed to send a message of de-escalation beyond the White House and the Kremlin to the wider world.

That message needs to register also in London. In reestablishing dialogue with Russia, as with Afghanistan, Biden is pursuing a policy that aligns him more closely with Trump than with his Democratic predecessor, Barack Obama. This is unlikely to be out of admiration for Trump, but because he judges this to be in the US national interest.

The UK, whose top brass and foreign secretary have been responsible for some of the harshest rhetoric against Russia in recent weeks, needs to take note, or it could find itself isolated and limping to catch up, as it did with the Afghan withdrawal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments