Predicted A-level system disadvantages Black students, experts warn

‘This form of assessment leaves room for teacher biases to determine a student’s worth, and in turn cement the next steps afforded to them,’ The Black Curriculum CEO tells Nadine White

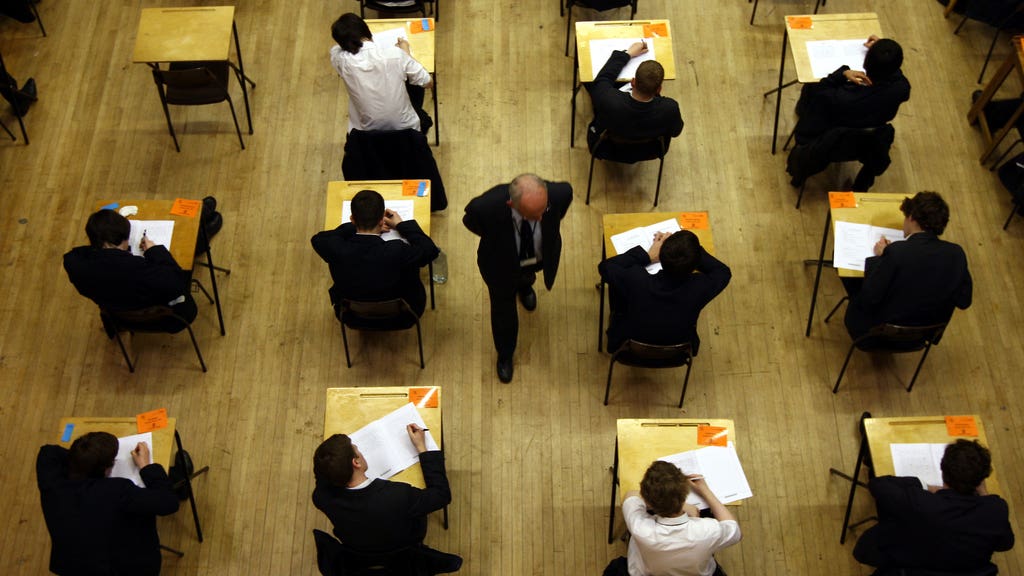

As students received their A-level results on Tuesday, based on teacher predictions rather than exams, there are fears that Black students are being severely disadvantaged.

Pupils have been assessed on what they have been taught during the pandemic, plus a range of evidence, including mock exams, coursework and in-class assessments using questions by exam boards.

Last year, government data showed that just 12 per cent of Black A-level students were awarded three A grades or higher – the lowest percentage out of the six aggregated ethnic groups. Attainment levels among this group have also lagged behind in previous years.

New analysis from Ofqual, published on Tuesday, shows that the longstanding gaps indicating lower outcomes of Black candidates, free school meal candidates, and those with a very high level of deprivation relative to their respective reference group, have significantly widened between 2019 and 2021.

The research shows that gaps indicating lower outcomes in 2020 for Black African, Black Caribbean and mixed white students relative to their white British counterparts, have increased by between 1.85 and 2.97 percentage points in 2021.

Meanwhile, Black educators and campaigners have expressed concerns that the predicted grades rollout overlooks a number of factors and is likely to make it even harder for Black and less privileged students to compete on a level playing field – from potential teacher bias to larger learning loss suffered during the pandemic exacerbated by socioeconomic inequalities.

History already paints a worrying picture when it comes to predicted grades.

Research conducted by University College London’s Institute of Education found that only 16 per cent of predicted A-level results are correct.

An earlier study, from before the pandemic, by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills found Black applicants had the lowest predicted grade accuracy, with only 39.1 per cent of predicted grades accurate, while their white counterparts had the highest, at 53 per cent; the same data also revealed that Black students are most likely to have their grades underpredicted.

Sociology teacher Rhia Marie, and founder of the Black Teachers Connect digital hub, told The Independent that various factors collide to potentially disadvantage Black students, under this new form of assessment.

The educator herself achieved seven A grades at GCSE, surpassing teachers’ expectations of zero As, and said: “There’s a consistent trend and pattern with students, especially Black students, being predicted lower than what they’re able to achieve. I am the perfect example to show that this does exist.

“We know that predicted grades can have a serious impact and it’s also important to look at the fact that these grades are not just based on one exam but on a holistic overview picture of students which means that sometimes teacher bias can play a role.

“There are a number of circumstances impacting on students, including both internal and external factors, from teacher racism, stereotyping and Eurocentric curriculum within schools to material and cultural deprivation outside of school. These aren’t taken into consideration when we look at predicted grades and sometimes predicted grades can literally be just a snapshot of that student and their capabilities.”

This comes as Sir Peter Lampl, the founder and executive chairman of the Sutton Trust education charity, said too many young people are going to university. “I think there are too many kids going to university. Too many graduates come out with a lot of debt – the levels of debt are astronomical – and in many cases they come out with skills that the marketplace doesn’t want,” he told The Telegraph.

Ziggy Moore, CEO of online tuition programme Moore Education, told The Independent: “University is now becoming undervalued. Everyone’s going to university and, even if you do have students from disadvantaged backgrounds going to university, it just doesn’t hold the same weight nowadays.

After a record level of students achieved an A grade on Tuesday, students from disadvantaged backgrounds will start university courses in record numbers this year, according to the Department for Education.

“So, on both sides of the coin, Black students are disaffected. If you’re the first generation to be able to go to university and transcend class, you will have a stain anyway because you were the Covid generation so your A-levels, GCSEs and degree won’t be viewed the same. Then this is compounded by the racial elements where Black children are affected so what this is going to cause is a greater divide.”

Mr Moore said this divide can be remedied by more Black families looking at alternative education options.

“With the Saturday school movement of the 1970s and ’80s, we saw the education system wasn’t treating our children right and provided an alternative solution. For some reason the community now seems to be looking to the government to bridge that gap as opposed to looking to ourselves,” he said.

“We know what the landscape is. and it’s solely down to us to put things in place like investing more heavily into supplementary education because that’s going to give us a fighting chance.”

Many parents of Black students are also concerned about how prepared their children are for a future in academia given the disruption that the pandemic has wreaked upon education over the past 16 months, Mr Moore added.

“Educationally we are going to see more and more disparity – that is now the order of the day. Following Covid, you’re already seeing divides in society: those who wear masks, those who don’t; those who are more in the digital world, those who are more in the physical world; the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. As the world moves forward, we’ll see more.”

Lavinya Stennett, CEO and founder of The Black Curriculum, said of the teacher-predicted grades: “This form of assessment leaves room for teacher biases to determine a student’s worth, and in turn cement the next steps afforded to them.

“At The Black Curriculum, we offer teacher training to equip all educators with the knowledge and skills to build a racially literate mindset and learning environment, a decolonised pedagogy and more. For many schools however, teacher biases working against students of certain backgrounds remain unchecked.

“For Black students in particular, grades will be predicted on the basis of assumed capabilities, stemming from generalised characteristics of their ethnic and socio-economic background.”

A spokesperson from The Runnymede Trust said: “For decades, qualitative research has shown that Black students experience systematically more negative teacher expectations than their white peers of the same gender and social class background, which is likely to also show in teacher assessments and predicated grades.

“We recognise the huge pressures faced by teachers and schools and commend the heroic work that they are doing in the face of this global pandemic.

“With the added cumulative impact of Covid and lost learning time over the past two academic years, we had hoped that teachers and schools would be better supported to assess effectively and mitigate against these risks of under predicting, and grade for potential.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments