Stargazing in August: Mission to a primeval Earth

Focus a small telescope on Saturn and you’re in for a surprise, writes Nigel Henbest

Down in the southern sky this month you’ll find a bright yellowish “star” with an oddity: it doesn’t twinkle. This is the planet Saturn, at its nearest and brightest on 14 August.

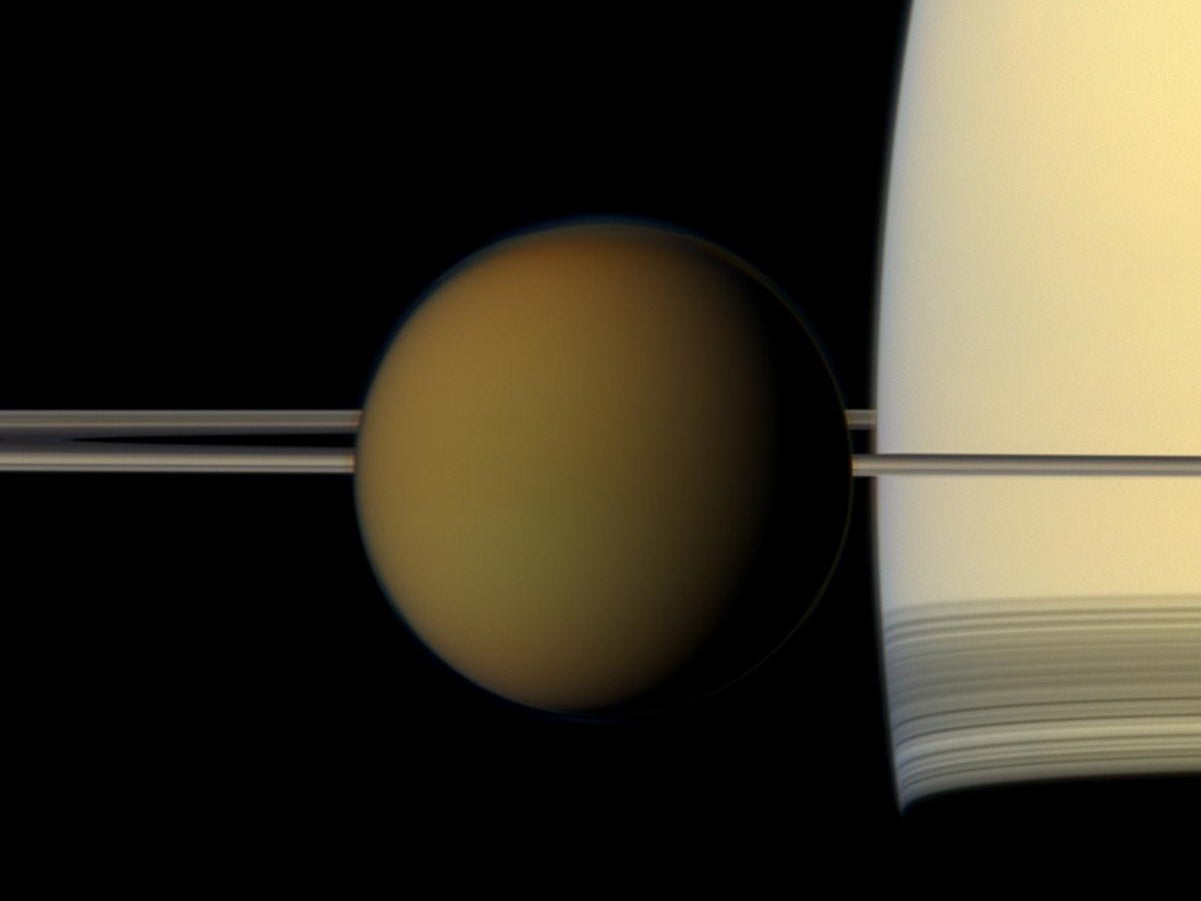

Focus a small telescope on Saturn and you’re in for a surprise. However many photos of Saturn’s famous rings you’ve seen, they don’t prepare you for the real thing. The ringworld looks three-dimensional, like an exquisite model hanging in front of the telescope.

And you’ll notice the largest of Saturn’s 82 confirmed moons, moving round the planet from night to night. Titan is bigger even than the planet Mercury and so massive that it holds on to an atmosphere that’s denser than the air we breathe on Earth.

Until 2004, we knew next to nothing about Titan. An orange haze permeates the atmosphere, making it impossible to see down to the surface. But that year, the Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn, carrying radar equipment that could penetrate Titan’s haze. It revealed large lakes on Titan’s surface. They can’t consist of liquid water: this far from the sun, it’s so cold that water is frozen solid. Instead, the lakes are filled with liquid methane and ethane – both gases here on Earth.

Piggybacked on Cassini was a small lander, Huygens, which parachuted down to Titan’s surface. As it descended, Huygens photographed dry streams and river beds where methane and ethane had rained down and flowed to the lakes. It touched down in a dried-up lake bed and photographed a pebbly surface through the hazy orange atmosphere.

And this ubiquitous smog is what excites scientists most about Titan. It’s made of tholins: complex mixtures of organic molecules, rich in carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen – some of the key ingredients of living cells. The tholins are created high in Titan’s atmosphere, where ultraviolet radiation from the sun breaks up molecules of methane and nitrogen in the air, letting them recombine into myriad different compounds.

Many scientists think that the same process occurred on the early Earth. But on our planet, things went a few stages further. The Earth was warm enough for water to be liquid. Rain washed the tholins out of the atmosphere and down into lakes and seas. Dissolved in water, the mess of chemicals could react to build up giant but well-ordered molecules – such as proteins, RNA and DNA – that created the first living cells.

So Titan is an early Earth in deep freeze; and in its frigid, dry conditions we can hope to explore the early stages of how life began on our planet.

Researchers are already planning the next stages of exploration. The powerful eye of the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope – which has already returned stunning images of the distant cosmos – will soon be turned to Titan to look for signs of two important molecules in its haze: pyridine and pyrimidine are key to the structures of RNA and DNA.

And Nasa is building a helicopter called Dragonfly, which will fly around in Titan’s thick foggy atmosphere and sample its smorgasbord of molecules at first hand. It’s an ambitious mission, but scientists are heartened by the success of the little helicopter Ingenuity that’s now zooming around on Mars.

To be launched in 2027, Dragonfly will land on Titan in 2034 and sample the organic gunge at various locations. The prime target – though the riskiest – will be landing beside one of Titan’s cryovolcanoes, frigid volcanoes that erupt not molten rock but liquid water. Here, scientists are eager to see if a watery solution of Titan’s tholins is producing the molecules found in living cells. On Saturn’s distant moon, we might witness a replay of the origin of life on our planet.

What’s up

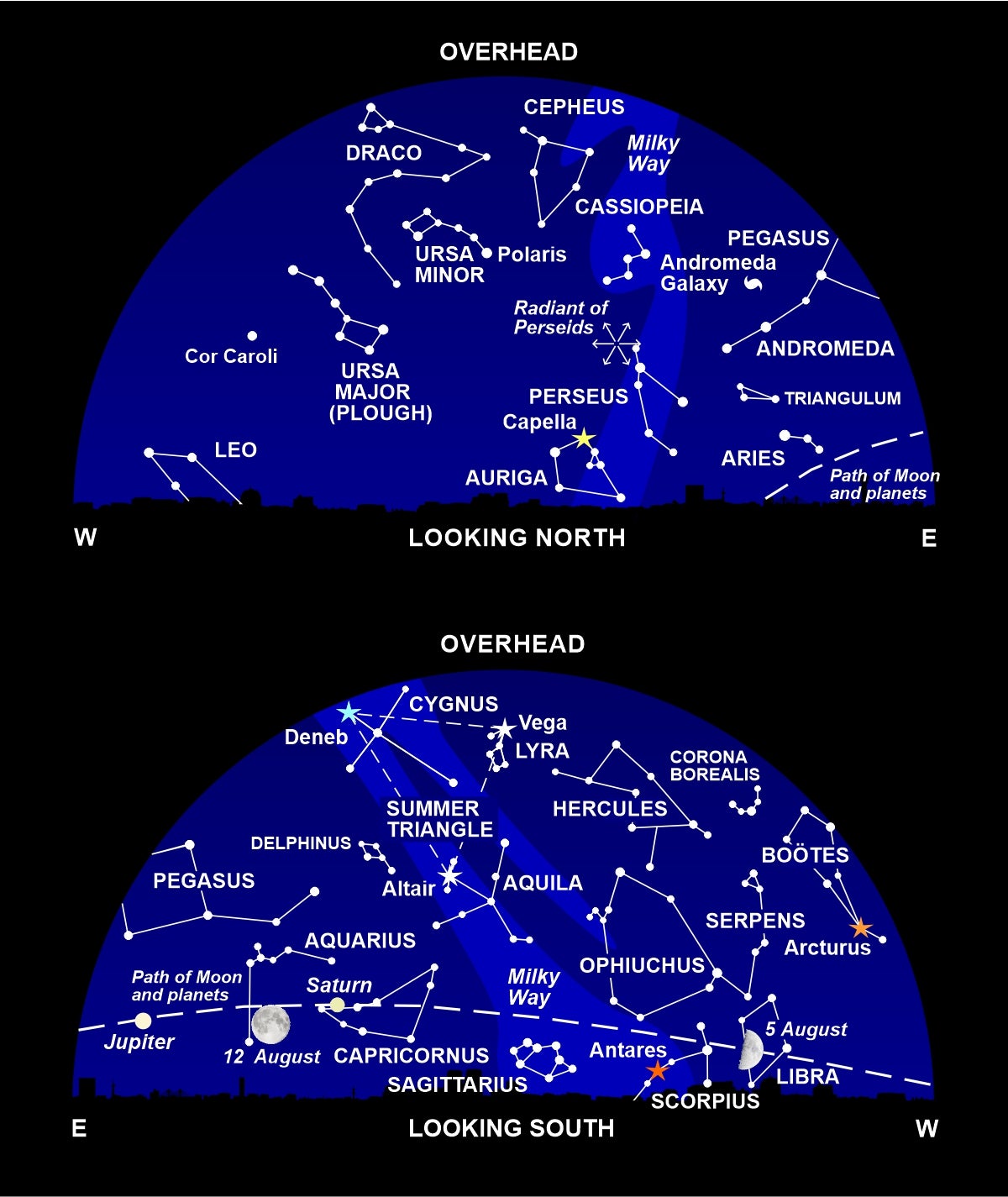

High in the south, you’ll find a giant triangle of three bright stars – known, appropriately, as the Summer Triangle. Near the zenith is Vega, the fifth-brightest star in the sky and the leading light of the tiny constellation of Lyra (the lyre). Vega is one of the closest stars visible to the naked eye, just 25 light years away.

Marking the lowest vertex is Altair, slightly nearer at 17 light years. Its name means “the soaring eagle” in Arabic, and it adorns Aquila – a star pattern whose Latin name also translates as “the eagle”.

The third star, by contrast is among the most distant of the bright stars: Deneb lies about 2,000 light years away, so the light we see left this star around the time of the Roman Empire. To appear prominent at such a vast distance, Deneb must be incredibly luminous, shining more brilliantly than 200,000 suns.

To the lower left of the Summer Triangle, Saturn is prominent in the faint constellation of Capricornus. And to the left again is giant planet Jupiter, rising at about 10pm and outshining all the stars. If you’re staying up later, look out for Mars clearing the eastern horizon at around 11.30pm, and then brilliant Venus rising at about 4am.

The annual Perseid shower of shooting stars reaches its peak on 12 August, but sadly we’ll miss all but the brightest meteors because the sky will be lit up by the full moon.

Diary

5 August, 12.06pm: first quarter moon

11 August: moon near Saturn

12 August, 2.36am: full moon, supermoon; maximum of Perseid meteor shower

14 August: Saturn at opposition; moon near Jupiter

15 August: moon near Jupiter

19 August, 5.36am: last quarter moon near Mars and the Pleiades

21 August, before dawn: Mars near the Pleiades

26 August, before dawn: moon near Venus

27 August, 9.17am: new moon; Mercury at greatest elongation east

30 August: moon near Spica

31 August: moon near Spica

Philip’s 2022 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments