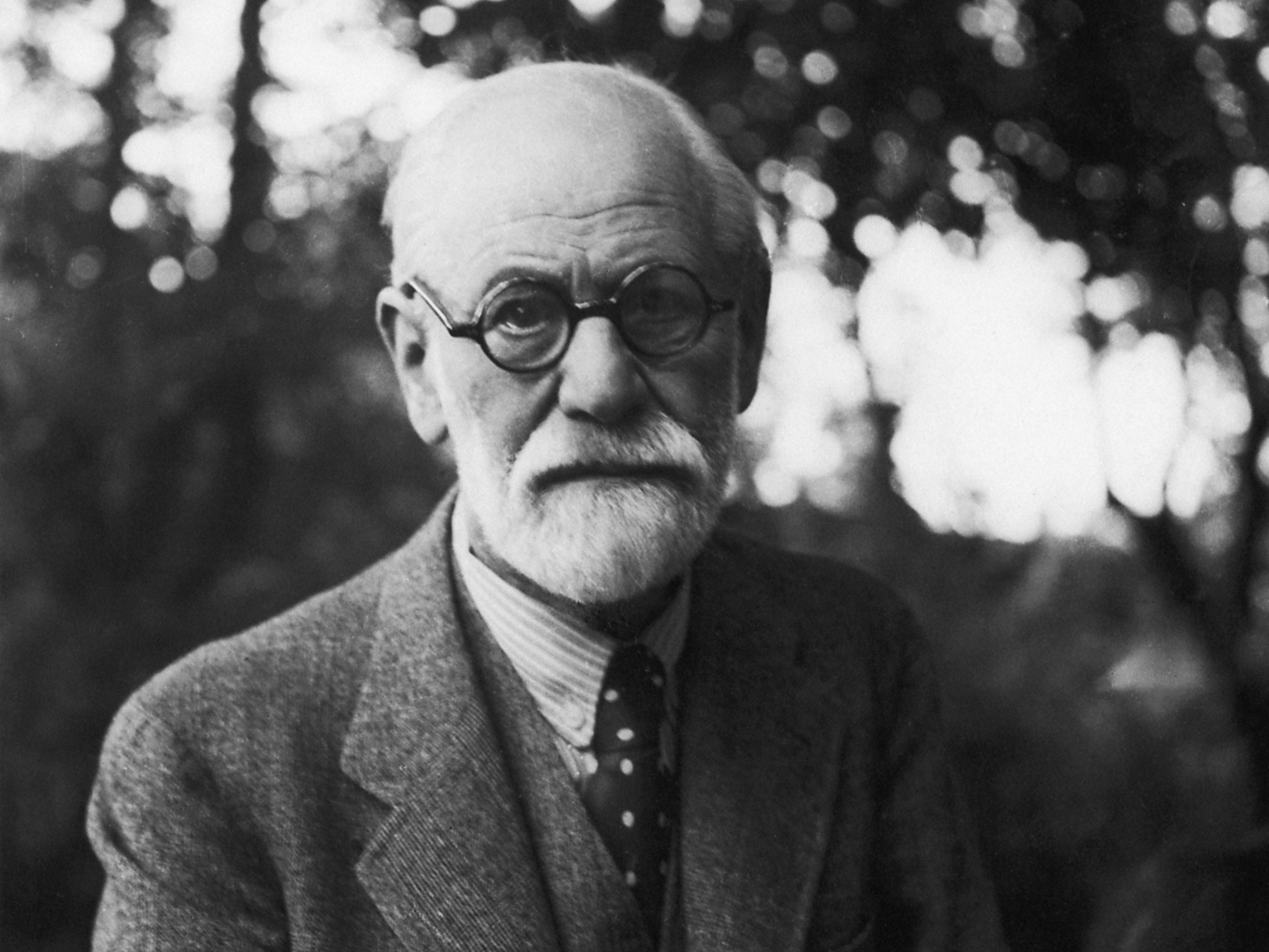

Sigmund Freud: driven by a dynamic unconsciousness

Freud believed that we often act for reasons that are a long way removed from our conscious intentions

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the founder of psychoanalysis, was born in the middle of the 19th century, an age characterised by rapid scientific and technological progress.

It seemed then that the power of human reason, allied with scientific methodology, would soon uncover the secrets of the universe, putting humanity fully in control of its own destiny. The enduring legacy of Freud’s work is that it undermined this confident view of the power and scope of human reason.

There is an irony here, in that Freud considered himself to be a scientist. He excelled at school, studied biology and then medicine at university, and opened up a medical practice in 1886. He quickly became interested in human personality, and by the turn of the 20th century had begun to develop the ideas that formed the bedrock of his psychoanalytic theory.

Freud’s major thesis was that human behaviour is driven by a dynamic unconsciousness over which we have little control: we often act for reasons that are a long way removed from our conscious intentions. This idea that personality has an unconscious aspect was not particularly novel. Freud’s innovation was the claim that it is possible for a psychoanalyst to get at the contents of the unconscious by employing techniques such as word association and dream analysis. The hope was that by knowing the unconscious roots of our thoughts and behaviour we would be in a better position to control them.

Freud was no mere theoretician, but also a practising psychoanalyst. Indeed, many of his ideas arose directly out of the therapeutic context. For example, in one notable case study, Freud argued that the fear of horses experienced by “Little Hans” was in fact a manifestation of his fear of his father, which was rooted in an Oedipal desire for his mother, which meant that his father was therefore a kind of love rival.

By the 1920s, Freud had developed his signature tripartite theory of human personality, which holds that the human psyche comprises three parts: the “id” – a person’s instincts; the “ego” – the rational, decision-making part of the personality; and the “superego” – the moral, censorious part. The id seeks the immediate satisfaction of its desires; however, in line with a “reality principle”, the ego has to balance the desires of the id against the demands of living in the world. It also has to keep the superego happy by ensuring that a person’s behaviour falls within the bounds of what is judged to be morally acceptable.

It was Freud’s view that many kinds of psychological distress are related to tensions between these aspects of the personality. It is the analyst’s job to bring these tensions to the surface, thereby reducing their power to harm. However, it is necessary to strike a cautionary note here: there is very little evidence that psychoanalysis has the therapeutic effect it is claimed to have.

Freud’s influence on 20th-century intellectual life could hardly have been more profound. Above all else, he showed that human beings are not as rational and free as they might like to think.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments