John Dewey and how we think

At the centre of his approach is his theory of inquiry, which aimed to show how thought emerges as people interact with their environments

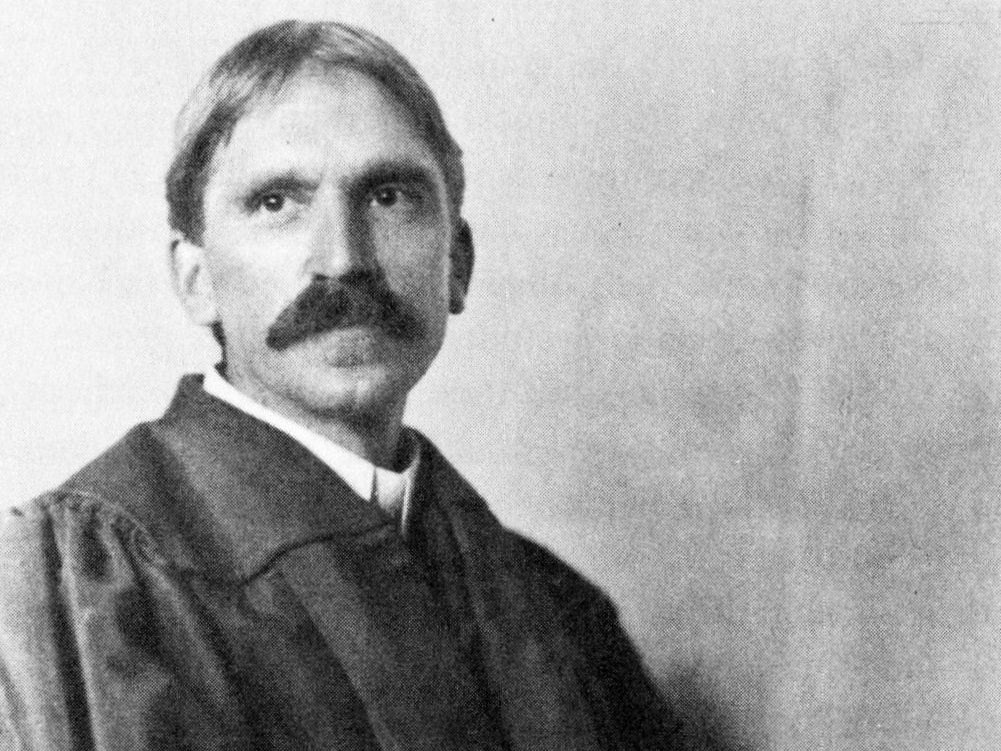

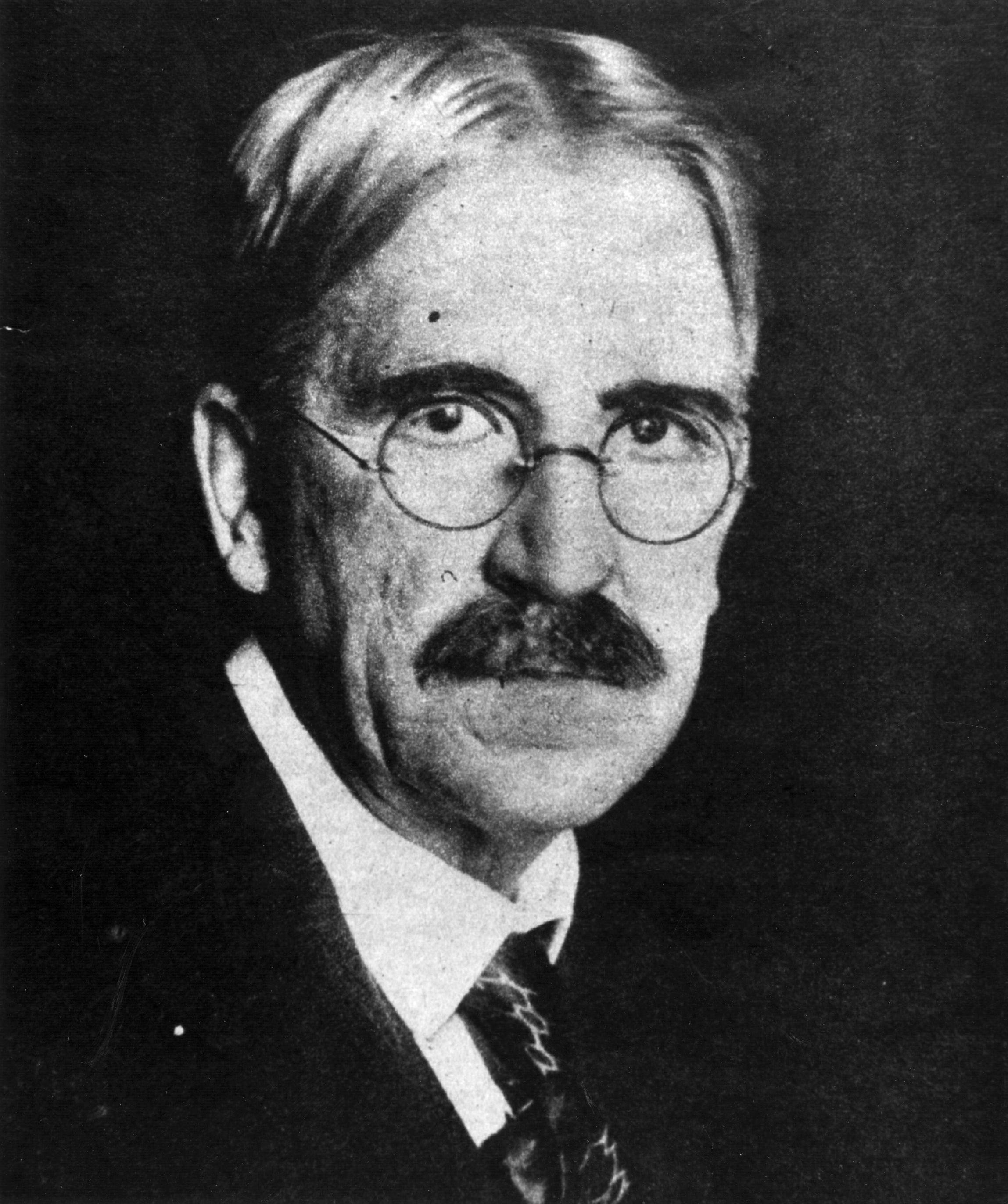

As well as a psychologist and progressive educational reformer, John Dewey (1859–1952) was one of the more influential American philosophers of the last century. With Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, he is associated with the pragmatic school of philosophy.

Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont, on 20 October 1859, the third of the four sons of Archibald Dewey and Lucina Rich. He was brought up in modest circumstances. His father, a grocer, made a comfortable living, but was not particularly ambitious on behalf of his children, though he had a passion for Shakespeare and Milton and was in the habit of reciting Burns to his sons. He would have been quite content for them to have become tradesmen.

Dewey’s mother, 20 years younger than her husband, was, however, of different character; more intense and ambitious, and it was mainly at her urging that the three surviving boys – the eldest sibling having died in infancy – pursued college educations at the University of Vermont.

It was as an undergraduate that the seeds of Dewey’s later intellectual commitments were first sown. Particularly, it was at this time that he came into contact with evolutionary thought, and the lessons he learnt were to stay with him for the rest of his life.

In the pre-modern world, species and organisms were seen as immutable, perfectly defined entities, the product of a benevolent designer. Darwin’s theory blew this idea apart, showing that the natural world is in fact dynamic and fluid, and that organisms and species are ever-changing as they interact with their environment.

This idea of iterative change became central to Dewey’s conception of human nature. He rejected the idea that humans have a fundamental essence, and all that this involves in terms of the ends towards which their lives are directed, and the means employed to attain these ends, arguing instead that human beings are constituted in their interaction with the multiple aspects of their environment. Humans are through and through the product of a lived practice.

It wasn’t only in the area of evolutionary thought that Dewey came to see the importance of a scientific way of thinking. As a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, he came into contact with G Stanley Hall, an experimental psychologist of international repute. Dewey was impressed with the power of the scientific method, and in his early writings he sought to reconcile it with Hegelian idealism. This, however, was not successful, and by the early 1890s, after he had taken up a position at the University of Chicago, he abandoned his idealism for the empirical, instrumental approach that he espoused for the next 60 years.

The theory of inquiry

At the centre of this approach is his theory of inquiry, which aimed to show how thought emerges as people interact with their environments, and how the measure of true belief – or belief for which there is warranted assertability – is that it facilitates satisfactory responses to the circumstances which people confront. Or, to put it another way, it provides successful rules for conduct.

The best way of understanding this idea is first to consider what Dewey meant by the notion of “habit”. As we have seen, he did not think that humans have a fixed, determinate nature. However, it is nevertheless the case that people tend to behave in fairly predictable ways. This is because they have learnt, via the process of socialisation, particular socially sanctioned habits. It is in this fashion that people are able to get by in their lives; they have adopted the modes of behaviour which function to achieve specific goals in particular circumstances.

For Dewey, value judgements are practical judgements; they guide the behaviour we exhibit towards the things which we value

However, sometimes these habits break down; the actions and responses people can draw upon prove inadequate in terms of the situations they confront, and they cannot go on. It is at this point there appears the kind of genuine doubt which necessitates inquiry. In How We Think Dewey emphasised that this sort of doubt is not purely cognitive, not the doubt of a sceptical philosopher, it is felt doubt:

In cases of striking novelty or unusual perplexity, the difficulty … is likely to present itself at first as a shock, as emotional disturbance, as a more or less vague feeling of the unexpected, of something queer, strange, funny, or disconcerting. In such instances, there are necessary observations deliberately calculated to bring to light just what is the trouble, or to make clear the specific character of the problem.

Having identified that there is a difficulty which needs addressing, in order to avoid the fairly ad hoc construction of possible solutions, the next stage in the process of inquiry is to isolate the significant elements of the problematic situation. Once this is achieved, then it is necessary to determine a number of hypotheses in order to solve the difficulty. This is a creative, imaginative process, and it involves going beyond what is given in the situation: “… It is more or less speculative, adventurous … it involves a leap, a jump, the propriety of which cannot be absolutely warranted in advance, no matter what precautions be taken.” (How We Think)

The final stages in the process involve working through the implications of the various hypotheses which are being entertained, and then, crucially, testing them experimentally:

Reasoning shows that if the idea be adopted, certain consequences follow. So far the conclusion is hypothetical or conditional. If we look and find present all the conditions demanded by the theory, and if we find the characteristic traits called for by rival alternatives to be lacking, the tendency to believe, to accept, is almost irresistible. (How We Think)

The resolution of this process involves the incorporation of new beliefs into the framework of habits which allows people to act in concert with the events in their lives. Truth is that which works. For Dewey, then, it is a mistake to think, following Descartes, that the fundamental epistemological question is to do with how we can know that the stuff in our minds, our perceptions, corresponds with external reality. Rather, what counts is whether our beliefs provide us with rules of conduct which help us to interact with the world.

There is an important point here about the status of true beliefs, or, to adopt Dewey’s terminology, “warranted assertions”. Like Peirce, Dewey is committed to a fallibilistic epistemology. Beliefs constitute knowledge when they are confirmed by a community of genuine enquirers. However, the extent of the warrant varies, and all beliefs are subject to revision, not least because the circumstances in which problematic situations arise are changed by the very act of finding solutions to them.

Dewey extends his theory of inquiry into the moral domain. Just as he denied that there was an inviolate human essence, so he denied that there were absolute moral standards – whether they be handed down by religious or philosophic authority – which remain true even in changing circumstances. The goal of moral action, then, is not to conform to a given code of behaviour, which would function merely to limit the expression of human potentiality, but rather to approach every situation with a view to constructing it in such a way that it offers the best opportunities for human fulfilment.

Value judgements

This point can be illustrated by considering how value judgements work. For Dewey, value judgements are practical judgements; they guide the behaviour we exhibit towards the things which we value (our “valuings”). Value judgements come into play when our normal activity towards our valuings has been disrupted by a problematic situation – for example, I have found that I cannot get to sleep if I drink coffee late at night. The point of the value judgement – I ought to drink warm milk instead – is to enable one to adopt a new course of action, if required, in order to solve the problematic situation. Thus, value judgements are tools which function to help us to live better lives.

It is only possible to engage in this kind of moral reasoning if we cultivate the same habits of inquiry which are appropriate for finding out new things about “the world”. The measure of the appropriateness of a value judgement is how well it works in the world; that is, whether it results in consequences which we value as we hypothesised that we would – did I, in fact, sleep better having drunk warm milk rather than coffee before bed? Value judgements, then, like the judgements we make about things in the world, are subject to empirical verification. They are also necessarily provisional and revisable in the face of changing circumstances.

To accomplish scientific and moral reasoning in line with the precepts of Dewey’s theory of inquiry requires that individuals are capable of flexible and sophisticated thought. There are clear implications here for the way that people should be educated. Particularly, Dewey argued that education should not be overly didactic in form; the idea is not simply to impart information which students will passively absorb. Rather, proper education aims to foster imaginative responses to new information and situations by engaging students in active, cooperative practices of learning. In this way, people develop the skills and habits required to enable them to function happily as full members of communities founded on principles of democratic participation.

John Dewey officially retired in 1930, but continued to teach as Professor Emeritus at the University of Columbia, where he had been working since 1904, until 1939. By this time, he was the pre-eminent figure in American philosophy.

Even after he finished teaching, this was not the end of his philosophical and public activities. Most notably, he was the chairperson of the Commission of Inquiry which, on investigating the charges made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow trials of the mid-1930s, found in favour of Trotsky and against Stalin.

Dewey died in 1952 at the age of 92. By this time, pragmatism was attracting less interest from professional philosophers. However, Dewey’s place as a major figure in the philosophical firmament is assured. His criticisms of the classical tradition in Western philosophy remain pertinent today. He is a major influence in liberal, progressive thought. And moreover, there are today signs of a revival of interest in his ideas, particularly in the work of people like Richard Rorty and Jurgen Habermas.

Major works

How We Think (1910)

This early work outlines Dewey’s theory of inquiry, and suggests that beliefs will be adopted or rejected on the basis of their usefulness in allowing people to master the situations which they confront in their lives.

Democracy and Education (1916)

It represents the most systematic articulation of Dewey’s ideas about education, stressing the importance of active, cooperative learning, and denying that education should be seen merely as preparation for civic and economic responsibilities. Also provides an interesting introduction to Dewey’s more general philosophical ideas.

Human Nature and Conduct (1922)

This book seeks to establish a moral theory based on the study of human nature. Although this will not solve all moral problems, it is argued that it will allow them to be posed in such a way that it might be possible to work towards solving them.

The Public and Its Problems (1927)

This defends the ideal of participatory democracy against critics who had argued that the nature of modern societies precludes anything more than a severely restricted kind of democracy.

Logic: The Theory of Inquiry (1938)

A major statement of Dewey’s pragmatism, and the theory of inquiry which underpins it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments