Raiders of the lost Iraq: A priceless cultural heritage is lost to looters

June 2003: Under the noses of the Anglo-American occupying forces, the priceless heritage of ancient Sumeria is being pillaged to order. Robert Fisk reports on the desecration of the birthplace of civilisation

It looks as though a B-52 has carpet-bombed the city called Mother of Scorpions. I clamber around 20ft craters and try to recognise one of the greatest cities of civilisation. But the thieves have done their work. They have broken or stolen everything. For 10 square miles, they have dug and smashed and gouged into the ancient earth, and destroyed the priceless heritage of Mesopotamia. The Sumerian palaces, the temple walls, the great pillars, oil lamps and giant pots and delicately patterned plates and dishes, all have been smashed to bits.

After three hours walking ankle-deep through the shards and fragments of dishes and handmade bricks, I found a tall, slender pot of green clay. One of our ancestors – one of my ancestors, I couldn’t help thinking – had worked on this pot more than 4,000 years ago. There was a slight indent on the bottom where his hand might have slipped, a long graceful neck up which his fingers must have passed many times, and then a thin lip at the top, sufficiently narrow that the potter must have brought his two hands so close that they might have been in prayer. It was then that I realised that the top of this beautiful thing was cracked, and only when I lifted it gently in my own hands did I realise the obscenity of the looter’s work.

This perfect, unbroken work of art, this treasure from the people who invented writing – who gave us the first laws and the calendar and mathematics and the wheel and the great epic of Gilgamesh – had been cast aside by the looters, tossed carelessly down a slope of sand and stone and snapped in two.

There were other plates and vessels lying smashed around me. The thief who had been digging here was looking for early Sumerian antiquities – the collectors of America, Europe, the Middle East and Japan want the pots and statues and jewels of 5,500 years ago, not the heritage of 2000BC – and so everything above the earliest layers of civilisation had to be thrown away. The robber probably took no more than 60 seconds to hurl away these pots and plates made 2000 years before Christ. It was the Sumerians who created our own concept of time, dividing it into units of 60. Alas, the looter’s only concession to history was the empty packet of cheap Iraqi cigarettes that lay beside the wreckage. Printed on it was a harp and the name of the manufacturer: “Sumer”.

The Mother of Scorpions – “Um Alkarab” – is in an area called Jokhr, the name of the nearest modern-day village some 40 miles northwest of Nasiriyah, although there is nothing modern about it. The clay “houses, with their wooden beams poking from the walls, their gatepost designs, and the small, intensely worked fields, are almost identical to those of the Sumerians who learnt, perhaps 7,000 years ago, to irrigate this land with the canals and ditches that brought the waters of the Tigris river to the desert. The canals are still there. “Saddam dried all of them and dammed the water,” one of the villagers told me. “Then, when the Americans started bombing, the waters flowed back for the first time in years.”

It’s about the only good thing the Americans have done for this ancient landscape. For the mass looting and destruction of the great Sumerian sites in the two months since the Americans “liberated” Iraq is likely to prove one of the most terrible cultural crimes of recent history, far more shameful than the calculated acts of robbery and vandalism at Baghdad’s Museum of Archaeology in April. Even now, this act of mass barbarism has scarcely been noted, let alone understood. Nimrud and Ninevah – the home of King Sennacherib – Hatra, Tel Naml, Tukulti, Tel el-Zabul, Larsa, Tel el-Jbeit, Tel el-Dihab and Kulal- Jabr have all been substantially looted and, in some cases, destroyed. American troops put a guard on Ninevah and Hatra – but only after the thieves had run amok there.

We may weep over Dresden. But over the past eight weeks, the extent of cultural loss in the land where civilisation began cannot be measured in tears. Part of ourselves has been destroyed, part of our humanity. We had been warned. And we did nothing. It is the greatest untold story of this latest war in Iraq.

There are tears aplenty at Um Alkarab, many of them running down the face of Eqbal Qazem, the 35-year-old deputy director of the Museum of Antiquities in Nasiriyah. She it was who prevented the looters of 1991 from thieving the antiquities of her museum during the great Shiite “intifada” against Saddam’s rule – the rebellion encouraged by president George Bush Senior and then betrayed when the Americans failed to come to the aid of the insurgents. As shooting broke out in the streets of Nasiriyah, she first fled the museum and then – fearing for the treasures she had grown to love – returned to sew the earrings and jewels from all the museum cases into her own clothes and then took a taxi to Baghdad. The government later rewarded her for her courage – then posted an ignorant Baath party apparatchik to run the museum and make her life a misery.

We may weep over Dresden. But over the past eight weeks, the extent of cultural loss in the land where civilisation began cannot be measured in tears

Twelve years ago, she risked her life for the heritage of the Sumerians. Now, she was stumbling around the wreckage of their history, her shoulders shaking, the tears dropping off her face into the hot sand. “How can I do anything but cry,” she says. “This is one of “the greatest tragedies to archaeology.” When I find a 3,000-year-old oil lamp – perfect only a few weeks ago “but now broken neatly in half – she takes it lovingly in her hands and runs her fingers round the bright red bowl. Then she throws it, choking on her tears, into the sand. “We can take nothing from this site – it is not allowed,” she says, and then laughs bitterly at such morality. The staff of the Baghdad museums must abide by the old Baathist rules – take nothing from the site lest they be accused of theft – while the real thieves, the big-time pros with order books to complete from Switzerland or New York or London, take out the treasures by the truckload.

And I mean truckload. The tyre marks of heavy lorries run right up to the stones of Um Alkarab. In the neighbouring city of Umma, seven square miles of antiquities destroyed just like Um Alkarab, the thieves are still at work. In fact, I walked right up to them as they sat outside their tents, strung out between amateur piles of excavations. They joke with the armed guards who are supposed to protect the site – and whom I increasingly suspect of sharing in the theft – and laugh when one of the local tribesmen, holding a Kalashnikov rifle, shouts across the wreckage: “We do not come to harm you.” The harm has already been done, not to them or us, but to that which belongs to us all under the soil.

“I don’t know who these people were,” one of the thieves tells me, grinning beneath his bright red kuffiah and holding up a large fragment of mid-Sumerian pottery, decorated with a clay band of rope. “I just dig down and take what I find and sell it.” But that’s not all he does. At Um Alkarab, there was a palace, its walls inlaid with bricks, each brick containing “the mark of the thumb and forefinger of its maker. They formed a facade to the palace, along with the nearby temple. Greedy for hidden jewels, the robbers have torn the bricks from the wall, ripping down the wall itself, destroying almost the entire palace. Nearby lies part of a large pot and in it some human remains many thousands of years old, two pieces of bone as white as ivory. One of the guards picks them up, snorts with derision and throws them into the sand. I pick them up and put them back in the fragment of pot before realising the truth; that it’s the life these people created – the life they gave to us, not their bones – that are sacred.

Joanne Farchakh, a Lebanese archaeologist who is conducting an exhaustive study of the mass post-war theft of Iraq’s cultural history for the French magazine Archeologia, and who puts her arm around Eqbal Qzem’s shoulders when her friend cries, believes that no archeological destruction on this scale has occurred for at least 1,000 years. “These cities are among the most important in Sumerian civilisation, and Um Alkarab and Umma are now effectively gone,” she says. They “have been destroyed. There was some looting before this war – in museums during the 1991 “uprising against Saddam and, for example, at Ninevah – where thieves stole pieces of a decorated wall.”

One piece of that wall was later found by British police – it was on its way to a collector in Israel – and later returned to Iraq. But three weeks ago, the thieves returned en masse to take the rest of the wall, and tore it to bits. “You have to understand what these collectors are like,” Farchakh says. “They want missing parts of their collection. They have, say, Akkadian pottery and Babylonian artefacts, and they have late- and mid-Sumerian, but they want early Sumerian so they put this on order – to complete their collections. The thieves who come here have order books to complete. They hack their way down to the early Sumerian period and destroy everything that is above it to fulfil their order. The same thing happened in the Baghdad Museum. The thieves there were looking for heads of 2,000-year-old statues, so they smashed the statues on the floor to get the heads off. They wanted heads of around 300BC. One of the statues simply broke into pieces.”

After I had crunched over the smashed pottery in the museum storage-room on 11 April, I compared the looting to the cultural genocide of the Second World War. But after visiting the Sumerian sites of southern Iraq - where infinitely more treasures were almost certainly discovered and then sold off to foreign collectors - I’m inclined to place the losses on a more epic scale, something proportionate to the burning of the great library of Alexandria in antiquity.

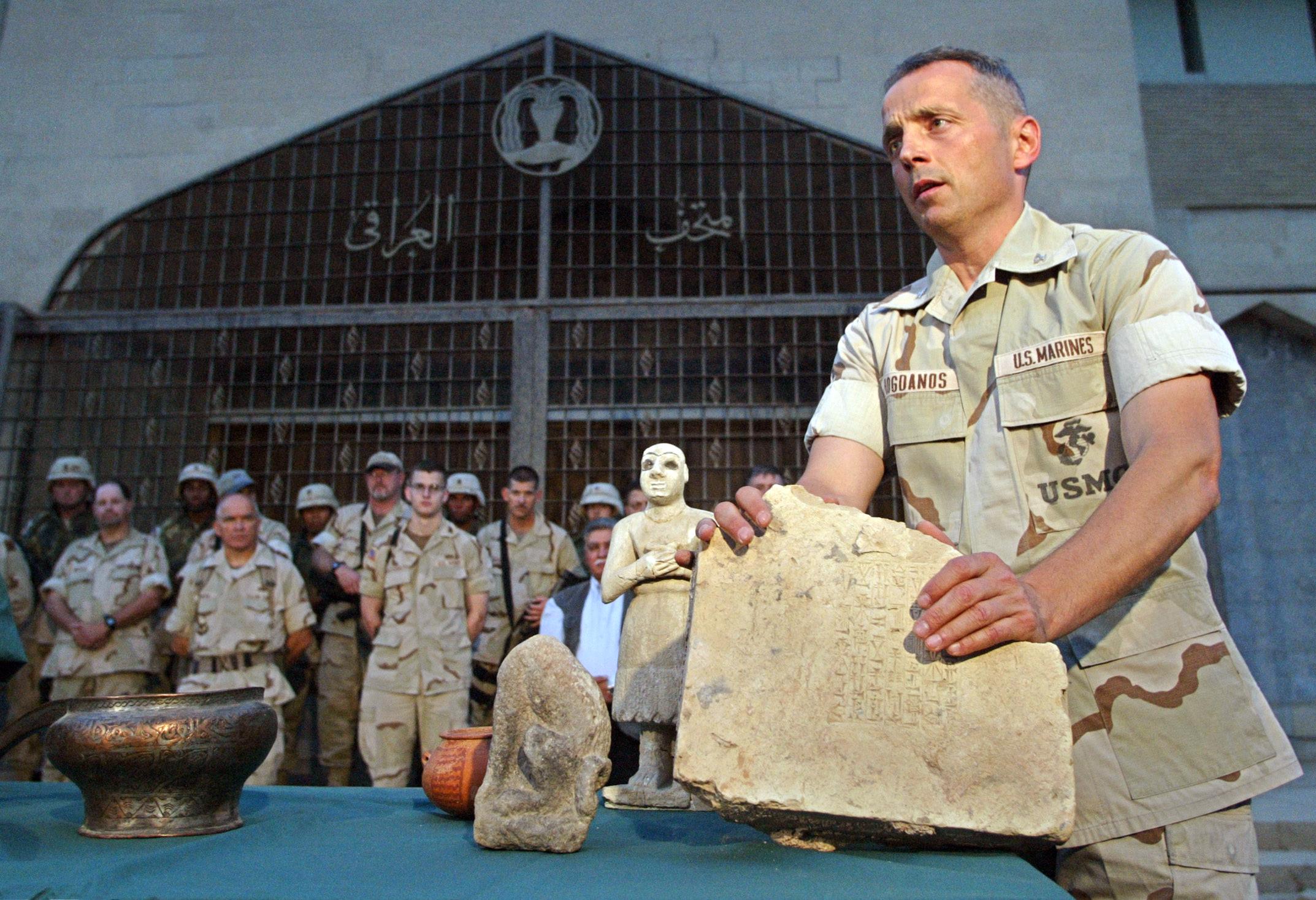

The Americans have desperately tried to square up their moral position by sending into Baghdad squads of FBI men, CIA agents and army intelligence boys to hunt down the missing artefacts. NYPD cops and United Airlines managers who are reservists for the intelligence corps are now reading the epic of Gilgamesh and learning how Semitic civilisation succeeded the Sumerians, founding the city of Babylon and the Assyrian capital of Ninevah. “Before I was posted to this investigation, I couldn’t even spell ‘Iraq’,” one of the intelligence men admitted to me last week. And the Americans have been trying to make things look good, at least for themselves.

No one in Iraq, and few academics in America, doubt that the US bears a heavy responsibility for the destruction of Iraq’s cultural heritage – even before the discovery of the mass pillage of the great Sumerian archeological sites that should provoke an even more passionate outcry than the looting of the Baghdad museum. International law, however, is vague about the duties of an occupying power. The Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 states that “pillage is formally forbidden”. This became part of the 1949 Geneva Convention, but the Geneva Protocols - which contain a paragraph on the “Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict” – was never signed by the US.

In any event, the pillage of Iraq – which is still going on under the eyes of the Anglo-American occupying power – is having a strange and powerful effect. When the market is glutted with stolen artefacts, prices usually fall. But today, they are rising sharply for Sumerian, Akkadian and Babylonian treasures. “So much of Mesopotamian history is now flooding the markets, that collectors want more,” says Joanne Farchakh. “They are voracious. The international markets hide these people from the law. Iraq’s soil is rich with these treasures that are being stolen.” And the occupying powers are doing almost nothing about it. Why should they? They don’t have to worry about the ancient city of Umma any more, nor the city called Mother of Scorpions. Because they no longer exist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments