Is now the time for Mark Zuckerberg to face the music?

In a tumultuous week that saw the accusations of a Facebook whistle-blower all but drown out the platform’s unprecedented six-hour outage, Sean O’Grady unpicks the profile of social media’s troubled behemoth

How was your week? Arduous enough no doubt, and we all have our challenges, large and small, but you most likely didn’t end up $7bn poorer than you were last Monday, have your public reputation shredded – again – with allegations of deliberately stoking online hate, and you didn’t let down a significant proportion of your 3.5 billion customers with an unplanned six-hour outage (the entire population of the world being about 7.8 billion, that is, just for context).

Of course, that was the week that was for Mark Zuckerberg, the 37-year old chief executive and chair of Facebook, the corporate behemoth that includes WhatsApp, Instagram and Messenger services, among others. Though nothing new in a sense – Facebook has been coming under fire ever since its launch from Zuckerberg’s dorm room at Harvard in 2004 aroused interest from the college authorities – these new accusations were somehow more acute, more personal, more tragic than the previous scandals about data harvesting and political interference.

In fact, “whistle-blower” is an inadequate term for the now-famous former employee turned whistle-blower, Frances Haugen, 37 (coincidentally the same age as Zuckerberg). She’s been tooting her flute in leaks to The Wall Street Journal, an interview on 60 Minutes and a respectful hearing at the United States Congress. She had some great tunes, too. She declared her old boss “morally bankrupt”; research conducted by Facebook itself, she claimed, proved that Facebook knew the damage that can be done to teenagers from their use of social media, but that its various platforms continued to exploit their insecurities, building traffic and thus advertising revenues, enhancing the $30bn a year or so it makes in profit.

Haugen clams that she saw internal Facebook evidence and has leaked documents that demonstrate that the company knew Instagram was damaging the mental health of young people, and did nothing about it; an algorithm “led children from very innocuous topics like healthy recipes … all the way to anorexia-promoting content over a very short period of time”. Some teenagers “traced the desire to kill themselves to Instagram”. Children are, allegedly, targeted as new users.

She maintains that they also knew changes to Facebook’s news feed, which many millions rely on and trust, had made the platform more divisive and polarising. In addition, Facebook was only pressured by extreme events to “break the glass” and restore safeguards as the Washington insurrection of 6 January unfolded. She points out that Covid anti-vaxxer comments are “rampant”, the company did nothing about ethnic hatred swirling around its Ethiopian service, and that it allowed stars to wreak “revenge porn” on others. According to Haugen, “the buck stops” with Zuckerberg and it’s all “an opportunity for Mark, for Facebook, to come in and say ‘we completely messed up’.” She’s taken the Facebook motto, “Move Fast and Break Things” quite to heart.

Zuckerberg attempted to dismiss Haugen’s allegations as illogical, on the grounds that they made no commercial sense

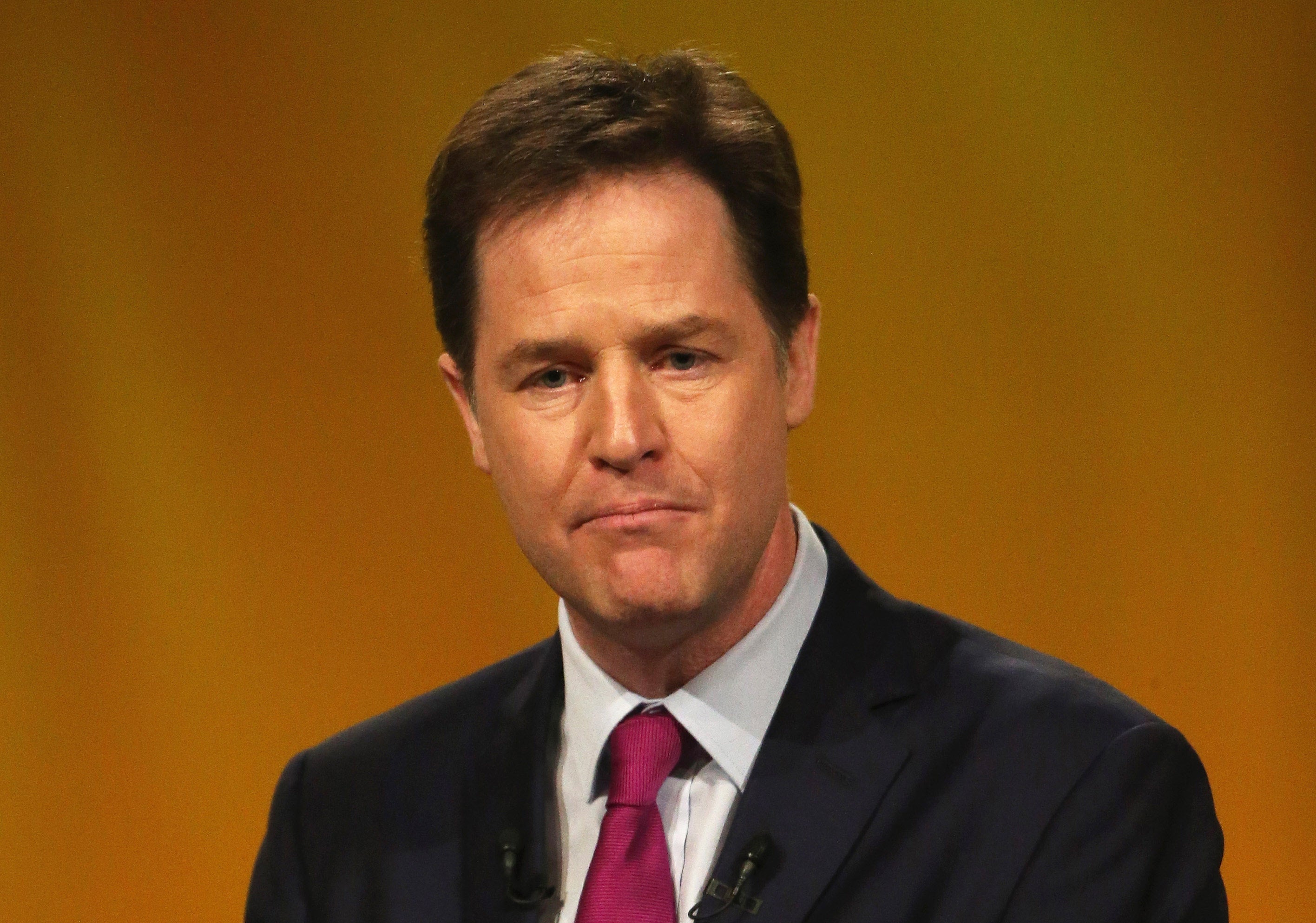

The only perverse saving grace for Zuckerberg was that his network of platforms were down for about six hours during the height of the whistle-blowing crisis, for which he apologised to his user base. However, and in stark contrast to the way he has handled previous flare-ups, he and his strategists (including the former British deputy prime minister Nick Clegg), have decided on a more “aggressive defensive” strategy.

So it was that Zuckerberg attempted to dismiss Haugen’s allegations as illogical, on the grounds that they made no commercial sense: “The argument that we deliberately push content that makes people angry for profit is deeply illogical. We make money from ads, and advertisers constantly tell us they don’t want their ads next to harmful or angry content,” Mr Zuckerberg wrote in a note to Facebook employees, “Many of the claims don’t make any sense.”

Moreover, Facebook folk are too nice to ever do such unpleasant things: “It’s difficult to see coverage that misrepresents our work and our motives. At the most basic level, I think most of us just don’t recognise the false picture of the company that is being painted.”

Naturally, he posted his remarks on his Facebook page for all the world to share. Zuckerberg’s Facebook page is headed “Bringing the world closer together”, though maybe not quite in the way he intended last week.

There’s plenty of debate about the future of his organisation, as there has been for many years. The old Zuckerberg approach – humble confession followed by promises to do better – has actually served him well. It certainly did after revelations about Cambridge Analytica, and the surreptitious harvesting of user data emerged after the 2016 US elections. That was the biggest crisis in the history of Facebook, but nothing much happened, as we now see. He was contrite about his “breach of trust” and was hauled before Congress for a five-hour grilling but emerged unscathed (he declined a parallel hearing at the House of Commons about the impact, if any, of Facebook data on the Brexit referendum). In any case, it must gall Zuckerberg that, having supposedly helped Trump get elected, he ended up having to suspend and then ban Trump from his platform for two years, earning Trump’s wrath and prospective revenge – “Next time I’m in the White House there’ll be no more dinners, at his request, for Mark Zuckerberg and his wife. It will be all business!”.

Indeed, so desperate is Zuckerberg to avoid public criticism and the possible destruction of his life’s work that he’s virtually begged the world’s governments to issue him with a moral compass and legal framework to operate under. “Facebook Clegg”, as he is now known, has openly canvassed a new global regulatory framework that will bring the excesses of Facebook, or its users, under control. The danger according to Clegg, speaking pre-pandemic, is that different regulators in different countries will tend to make global networks (ahem, like Facebook), retreat behind national borders, thus making it more difficult for Facebook to be “bringing the world together”.

“Mark Zuckerberg has become more anxious that Facebook is being asked to regulate itself in a way that no private company should be expected to do,” said Clegg. “He's been asked to preside over areas that he can't do on his own…Global leaders need to grapple with these ideas. If not, we will get an ever-more Balkanized internet.”

At times Zuckerberg does seem to acknowledge that Facebook is something nearer to a publisher and broadcaster than a mere “platform”. In an interview with George Stephanopoulos in 2019, he said: “I think companies should be responsible for having proactive enforcement of issues on their platforms, right? If someone is trying to spread terrorist propaganda, for example, that's an area that we've built systems that are quite advanced for now. Now, 99 per cent of the Isis and Al Qaeda content that we take down, our AI systems identify and remove before any person sees it, right? So that’s a good example of being proactive and, I think, what we should hold all companies to account to be able to do. There's a separate question about, how do you make the decision about what content should be allowed in the first place? And there, you know, every country has a different tradition. In the US, we have the First Amendment and strong protections around free speech. So maybe the government won't get involved directly in deciding that…”

So far, all he has to guide him is an independent Oversight Board, who were the people who banned Trump.

Clearly, Zuckerberg is conscious, too, that anyone who peddles news and views is going to come under the scrutiny of politicians – one reason surely why Facebook periodically changes its algorithms and reduces its news output, much to the dismay of the mainstream media. Zuckerberg is smart enough to spot the hazards ahead.

His bland, almost featureless face still looks youthful, he smiles easily, has a tendency to new-age nerdspeak and constantly trumpets his pride at being an open and generous millennial

It’s no shame that Zuckerberg may be merely trying to preserve his life’s work from destruction, either through public revulsion and user boycotts (#DeleteFacebook) or radical official action. He has always seemed genuinely motivated by something other than (or at least as well as) the absurd wealth he has amassed. He’s never wanted to sell all of his stake in the company and walk away, and lost almost all his senior colleagues in an early dispute about cashing in on their success. On the other hand, Wall Street and the Nasdaq has allowed him to develop a very convenient share structure, where he controls 60 per cent of the voting shares, while his current economic interest is down to a mere 3 per cent. So he can still keep custody of his child, but cash in on its astonishing financial success.

You can still see, though, some of the spirit of the young Zuckerberg. His bland, almost featureless face still looks youthful, he smiles easily, has a tendency to new-age nerdspeak and constantly trumpets his pride at being an open and generous millennial. He is the richest young-ish man in the world. He intends to donate 99 per cent of his money to his charitable foundation, albeit gradually. He doesn’t mind immigrants, and he’s a supporter of equal LGBT+ rights. He is a fairly identikit rich liberal, though like the rest of the billionaire club, with a clear conviction that enterprise and free markets are the key to the wealth of nations, not least China in the past few decades.

In a commencement address to Harvard graduates a few years ago Zuckerberg (who dropped out to build his social network) joked that if he got through his speech it would be the first thing he’d completed at Harvard. He explained, apparently sincerely, that he was just having some fun, like the Facemash site he’d invented as a student, by turning the traditional printed college photo phone directories, nicknamed facebooks, into a kind of primitive dating app, and the first virtual social network.

Zuckerberg told the grads: “I remember the night I launched Facebook from my little dorm in Kirkland House…I remember clearly telling my friend that I was excited to connect the Harvard community, but one day someone would connect the whole world. The thing is, it never occurred to me that someone might be us. There were all the big technology companies with all these resources and I just assumed one of them would do it. But the idea was so clear to us that all people want to connect. So we just kept working on it, day by day”.

He also took the opportunity to have a little fun at the makers of the film The Social Network about him and his creation: “The idea of a single eureka moment is a dangerous lie… and no one writes math formulas on glass.”

It is possible, even likely, that he had no inkling when he was a 19-year old student that his little experiments – he tried inventing games, study tools and messaging systems – would spawn such a formidable business model. Or, rather, a variant of the business model pioneered by Google and Amazon, namely to get the public to give you lots of information about themselves and then either sell the data or use it so they can sell more stuff to you. It’s low cost and high revenue, and, once you reach critical scale, remarkably difficult for others to enter the field.

It has certainly worked for Facebook, and, having acquired and built up Instagram and WhatsApp and Messenger, it seems that Zuckerberg still has a universalist ambition for his business. Looking across the Pacific to China, where Facebook is relatively weak, he can see the success of his equivalent, the ubiquitous Chinese WeChat, where social networking, messaging, payment systems and commerce are all rolled into one. In other words, consciously or not, he’s out to emulate what Amazon and Google and eBay/PayPal do. In order to get anywhere near that, safely, he will need to shelter under the umbrella of a benign international regulatory regime. If not, then the fact that the Americans, Chinese and Europeans will never be able to agree will allow him to continue as best he can, dividing and ruling along the way.

For such a huge figure Zuckerberg is not an extraordinary personality. Unlike Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, his fellow centi-billionaires, he has no interest in becoming an astronaut: “I’m much more focused on virtual reality, which would let anyone teleport anywhere in the world or in the universe without having to physically strap themselves into a rocket.” Boring!

Nor is his private life stratospherically exciting. He’s still with Priscilla Chan – he chatted her up while they were queuing for the loo at his Harvard leaving party – and they have two daughters. He comes from an upper-middle-class family in New York (dad was a dentist and mum a psychiatrist), and he has three sisters. He was brought up Reform Jewish and has reportedly become interested in the religious side of his heritage, and is still boyishly excited by gadgets and tech.

Zuckerberg perhaps genuinely believes that he can reconcile what he thinks he is doing with what is actually happening, at least according to his critics. I am, though, haunted by a story from early in the Facebook story, back in his Harvard days, when the network was no more than 4,000 strong. It was revealed much later, in a series of instant messages to a colleague. The conversation goes as follows:

“Zuck: yea so if you ever need info about anyone at harvard just ask

Zuck: i have over 4000 emails, pictures, addresses, sns

Friend: what!? how’d you manage that one?

Zuck: people just submitted it

Zuck: i don’t know why

Zuck: they ‘trust me’

Zuck: dumb fucks”

Zuckerberg didn’t deny any of this, but said he “absolutely” regrets it: “If you’re going to go on to build a service that is influential and that a lot of people rely on, then you need to be mature, right? I think I’ve grown and learned a lot… I think a lot of people will look at that stuff, you know, when I was 19, and say, ‘Oh, well, he was like that... He must still be like that, right?’”

People such as Hagen do think he’s like that, because she told her audience of senators and the rest of us last week that: “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division and weaken our democracy. The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer, but won’t make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people.”

We’d all love to see what Zuckerberg said about all that on his WhatsApp group. It might bring the world a little closer together.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments