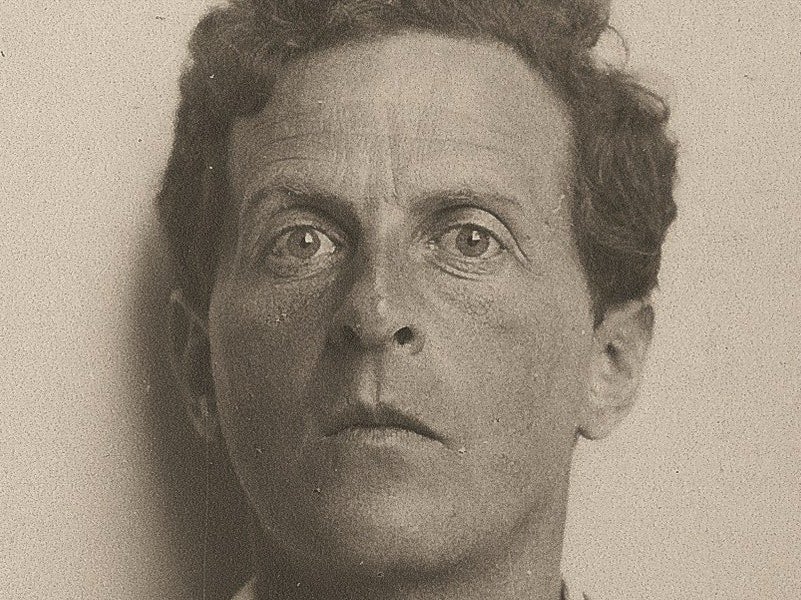

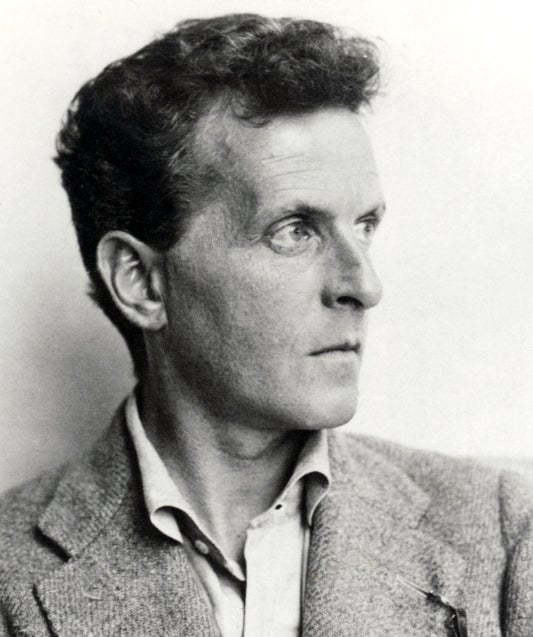

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The greatest intellect of his day?

Perhaps better known for waving a poker at a fellow philosopher, Wittgenstein sought to define meaning

Many people believe that Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) was the 20th century’s most important philosopher. It is somewhat ironic, then, that he is probably best known for waving a poker at fellow philosopher Karl Popper.

The setting for this peculiar event was a meeting of the Cambridge Moral Science Club in October 1946. There are different accounts of precisely what took place, but the general gist of it is that in the midst of a heated discussion about the validity of moral rules, Wittgenstein picked up a poker, gesticulated with it in order to make a point, and then abruptly departed the scene. Popper is said to have subsequently given as an example of a moral rule that one should not threaten visiting lecturers with pokers.

Wittgenstein’s biographers all agree, as this story suggests, that he had an intense, if compelling, personality. He was born in Vienna on 20 April 1889, the youngest child of Leopoldine and Karl Wittgenstein. His father was a rich and successful Austrian industrialist and enjoyed a position of some prominence in Viennese society. The Wittgenstein home was a centre of cultural excellence; Brahms and Mahler were frequent visitors, and the young Wittgenstein was encouraged in these early years, particularly by his mother, to develop his own musical interests.

His formal education, however, was a little unorthodox. He did not attend school until he was 14, and then not very successfully. It was assumed that, like his father, he would become an engineer – indeed, he had shown some aptitude in this direction – so, having failed in his ambition to read physics at university, he went off to study engineering, first in Berlin and then in Manchester. It was while at Manchester that he became interested in philosophy; he had read and been impressed by Bertrand Russell’s The Principles of Mathematics, and on the advice of Frege, with whom he had corresponded, he went to Cambridge in 1912 to study with Russell.

The picture theory of meaning

Although it was immediately clear that he was a brilliant thinker, he only stayed in Cambridge for a short while, opting instead to travel. However, this was interrupted in 1914 by the start of the First World War. Wittgenstein immediately joined the Austrian army, serving mainly on the eastern front. During this time, he worked on the manuscript of the book that would eventually become Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, his first great work.

Language marks the limits of thought; therefore, if it isn’t possible to say something clearly, it isn’t possible to think it without falling into nonsense

The Tractatus was eventually published in 1922 with the help of Russell. It is a short book, only 70 pages long, but Wittgenstein, for a while at least, seemed to believe that it solved all the genuine problems of philosophy. The book set out what is known as the picture theory of meaning. The world is constituted by a set of atomic facts. Propositions – for example, “The cat is black” – are logical pictures of actual or possible facts; in other words, propositions stand for possible states of affairs of the world. If the state of affairs picked out by a proposition obtains in the world, then the proposition is true. Thus, it was Wittgenstein’s claim that the underlying logical structure of language mirrors the logical structure of language, which in turn mirrors the logical structure of the world.

It must be said that it is hard to be clear about Wittgenstein’s argument unless one has a thorough grounding in the issues that informed the work on language and logic of people such as Frege, Russell and Whitehead. However, there is an interesting general point about Wittgenstein’s argument in the Tractatus. It was his view that language allows things to be said clearly or not at all: “What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.”

Moreover, language marks the limits of thought; therefore, if it isn’t possible to say something clearly, it isn’t possible to think it without falling into nonsense. Part of the significance of this argument is that it led Wittgenstein to the thought that philosophy is a highly circumscribed endeavour. It is mainly about policing the limits of language; ensuring that that we don’t fall into the error of mistaking nonsense for meaning. Indeed, Wittgenstein famously said at the end of the Tractatus: “My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognises them as nonsensical.”

Nonsensical or not, Wittgenstein took his cue from the publication of the Tractatus to give up philosophy for a while. He disappeared to Austria, where he took a job as a schoolteacher. This was not an entirely successful endeavour. There were accusations of almost tyrannical teaching practices – including an alleged incident of violence towards a female student (though there were no reports that a poker was used!) – and eventually he gave up teaching to become a gardener at a monastery. At this point, something interesting happened. Wittgenstein began to talk with some of the members of the Vienna circle group of philosophers – in particular, with Moritz Schlick – and he came to the view that perhaps the Tractatus had not solved all the genuine philosophical problems after all.

This reassessment led to the second phase of Wittgenstein’s philosophical career, in which he developed ideas that in many respects were completely at odds with his earlier philosophy. In particular, he came to believe that the idea that language is a determinate system, within which simple propositions stand for states of affairs of the world, was fundamentally misconceived. Rather, language is multifaceted and context-dependent; it is used for and accomplishes many different things. Thus, for example, it simply isn’t possible to say how the phrase “I love you, too” will be understood unless the context in which it is said is known. To say it in response to an insult is to intend something entirely different from if it is said to a lover in a tender moment. Meaning is inextricably tied to the behaviour of language users and the contexts in which they employ speech acts.

Philosophical investigations

These new ideas about language and meaning were articulated most significantly in the posthumously published Philosophical Investigations. In this work, Wittgenstein set out to show that language gains its meaning from the way in which it is used: “For a large class of cases – though not for all – in which we employ the word ‘meaning’ it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”

Linked to this idea is the notion of a “language-game”: the ways and contexts in which words are used depends upon the ‘game’ being played. The idea of the language-game brings into focus the fact that language is linked to specific activities, or particular “forms of life”. Wittgenstein mentioned as examples the following: giving orders and obeying them; reporting an event; speculating about an event; putting together a hypothesis; joke-telling, cursing, and story-telling. Much of Investigations is concerned with flagging the differences within and between various language games.

A private language

Perhaps the most talked-about section of Investigations is where Wittgenstein argues against the possibility of a private language. The argument is not presented in a standard way, with premises, deduction and conclusions. Rather, in line with the style of the book as a whole, it is constructed out of a series of short statements, with little explication of their meaning and intent. Consequently, there are many different interpretations of the private language argument; what follows, therefore, is just one particular interpretation.

Wittgenstein asks whether it is possible to imagine a language in which a person could write down or give vocal expression to his inner experiences – his feelings, moods, and the rest – where the “individual words of this language are to refer to what can only be known to the person speaking… So another person cannot understand the language.”

To consider this possibility, he imagines the case where a person writes down “S” in a diary every time they experience a certain sensation. In this way, it seems possible to arrive at an ostensive private definition of “S”; every time the sensation occurs, and only when it occurs, the sign “S” is reproduced in thought or in writing, thus establishing a permanent connection between “S” and the sensation, and thereby the meaning of the sign.

However, Wittgenstein identifies a problem with this argument. It isn’t clear that we can ever establish the link between the sign “S” and the sensation in such a way so that on those occasions in the future when we employ the sign, we can be confident that we’re using it correctly. In other words, in a private language there is no clear difference between remembering the correct application of a sign, and believing that one has remembered the correct application of a sign. As a result, the sign lacks meaning; nothing can ever establish that it is being used correctly. It follows, therefore, that a private language that refers to sensations is not possible; words gain their meaning from their use in a public context.

Although in his later work Wittgenstein largely came to reject the arguments that he had put forward in the Tractatus, it would be wrong to suppose that the discontinuity between his early and later periods was total. In particular, his view of the nature of philosophy remained constant. It was Wittgenstein’s belief that the task of philosophy is to uncover and analyse the various ways in which we are befuddled and confused by language. As he put it in Investigations, philosophy “is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language”.

Wittgenstein is one of the most interesting of the great philosophers. His work, of course, has been tremendously influential. It was, for example, directly implicated in the emergence of “ordinary language philosophy” after the Second World War. He is also interesting for reasons that are not directly to do with his philosophical output. His force of personality, for example, is renowned. He was a demanding, dramatic and intense teacher. Many of the people who attended his seminars at Trinity College were afterwards unable to imagine philosophy being conducted in any other way. He was also exceptional in the sense that he was not a scholar; he knew little of the standard texts of the philosophical canon, and indeed, he encouraged his students not to bother reading them. Yet he produced two distinct bodies of work, each of which would have been sufficient to establish his reputation as a great philosopher. It is quite easy to understand, then, how it is that Bertrand Russell came to consider him to be perhaps the greatest intellect of his day.

Major works

Tractatus-Logico Philosophicus (1922)

The major work of Wittgenstein’s early period, and a classic of 20th century philosophy. Outlines a picture theory of meaning, according to which meaningful propositions stand for particular states of affairs of the world. A very short (20,000 words), yet hugely influential work, it was inspired by the writings of Frege, Russell and Whitehead.

Philosophical Investigations (1953)

The most important work of Wittgenstein’s later period, it represents a systematic expression of the ideas that he came to hold about language and meaning. It includes an analysis of concepts such as “language-game” and “forms of life”, and pursues the idea that words gain their meaning from the rules that govern their usage.

The Blue and the Brown Books (1958)

Although published posthumously, these books originate from the mid-1930s. They were dictated by Wittgenstein to his students, and constitute a useful introduction to the ideas of his later period.

On Certainty (1969)

A collection of writings on epistemology – knowledge and certainty – from the last few years of Wittgenstein’s life. Primarily sourced from his notebooks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments