The death-row killer who inspires the children of Peru

Norio Nagayama spent years in isolation, never knowing what day would be his last. That day came in August 1997 when he was finally executed for murdering four people. But why does this teen killer wield so much influence in Peru? Cherry Casey explains

Norio Nagayama was born in 1949 in Abashiri, the northernmost part of Japan that sees harsh winters where temperatures drop to -14C. He was one of eight children, born into extreme poverty. “His father was a gambler who didn’t care for his family, and his mother was left to raise the children,” explains Kyoko Otani, former defence lawyer for Nagayama.

Unable to bear her life, Nagayama’s mother left Abashiri and travelled south, to Aomori, to stay with her parents. She took only her infant children with her and left Nagayama, who was five years old at the time, behind with his older siblings. They subjected him to brutal physical violence.

The children were eventually found by the welfare department in freezing and starving conditions, and taken to live with their mother, but Nagayama continued to suffer neglect and violence at the hands of his family. His father, who had gone missing some time earlier, was later found dead on a roadside in Gifu. In a photo sent to Nagayama’s mother for identification purposes, he was simply “a dead figure drooling in the street”, says Otani – and it affected Nagayama deeply.

Nagayama left school at 11 and moved to Tokyo at 15 to find work. He continued to live an incredibly unhappy existence on the margins of society, and attempted to take his own life several times.

Around this time, Nagayama broke into a US military base in Yokosuka and found a small handgun, which he started to carry around with him, “like a talisman” says Otani. But when he was later caught trespassing in a hotel, and chased by a security guard, he used the gun to kill him. In the month that followed, Nagayama fatally shot another security guard and two taxi drivers. He was 19 years old.

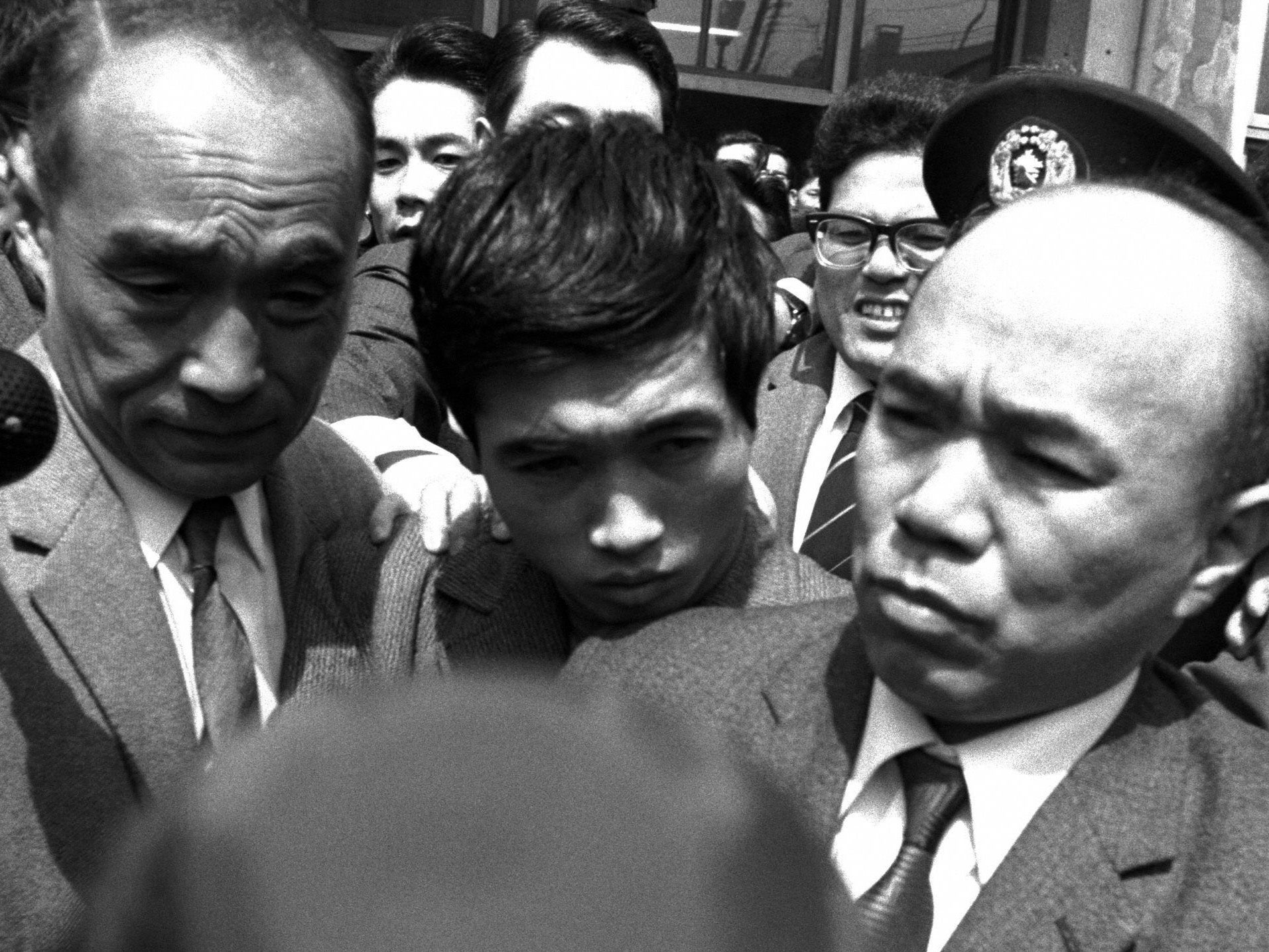

Five months later, in April 1969, Nagayama again wanted to end his life. This time, he decided he would break into a high school in Tokyo and wait to be found by police. When they arrived, he planned to fire at them, so that they, in turn, would shoot him to death. But when the time came, Nagayama did not shoot. Instead, he was arrested and taken to a detention centre in Tokyo.

While incarcerated, Nagayama shared a cell with a man who had been heavily involved with the student movement, which was very active in Japan at that time. He learnt a lot from his cellmate, explains Otani, “about communism, the capital, and how poverty was created.”

Despite having received only the bare minimum of a primary-school education, Nagayama began to study voraciously, as well as document his own thoughts and feelings, often in the form of poetry.

Throughout this period he had to attend various trials, one of which was attended by a publisher who learnt of Nagayama’s poetry journal and convinced him to have it published. It was, in 1971, under the title Muchi no Namida (Tears of Ignorance) and became a best-seller. Until then, the “class struggle” was often written about as an idea or concept, Otani explains. Nagayama wrote about it specifically, from lived experience and with the sensibility of a young boy. “It impressed many people,” says Otani and Nagayama became famous.

In 1979, 10 years after his arrest, Nagayama was sentenced to death by the Tokyo District Court. Two years later this was successfully appealed and commuted to life imprisonment, primarily on the grounds that Nagayama had only just turned 19 when he committed his crimes, and should have been treated as a minor (18 or younger), for whom the death penalty was not applicable.

“Considering his history of being abandoned in a desolate place, growing up in extreme poverty and let down by the welfare services, it was deemed [by the High Court] that his mental maturity was not developed in an age-appropriate matter,” says Otani. “It was also well-known that he had got married in prison and tried to [achieve some form of] consolation for victims’ families,” she adds. “It was judged that he should live and atone.”

Nagayama had always shown remorse for his actions, publishing his work on the condition that the royalties were donated to his victims’ families. But he also wished to be seen as an example of what can happen to an individual when extreme poverty and neglect pushes them to the very outskirts of society, and he used his writing to do this. After Tears of Ignorance, Nagayama wrote eight more novels, one of which – Kibashi (Wooden Bridge), based on the delivery job he held as a young child – won Japan’s New Literature Award in 1983.

Nagayama had always shown remorse for his actions ... he also wished to be seen as an example of what can happen to an individual when extreme poverty and neglect pushes them to the very outskirts of society

However, nine years after the reduction in Nagayama’s sentence, case prosecutors argued that life imprisonment was too light a punishment for four murders and that the case should be brought back to the Supreme Court. They were successful, and Nagayama’s sentence was changed once more to death by execution.

He was “tossed about by society to the end of his life,” says Otani and after the ruling his mental health plummeted, his marriage ended and he spent the rest of his life in near isolation, not knowing which day would be his last. (Still today, death row inmates in Japan are kept in solitary confinement for years on end, told when they will be executed only on the morning itself.)

That morning arrived for Nagayama on 1 August 1997, seven years after his final sentencing, aged 48. Japanese executions are carried out in secret. There is no opportunity to say goodbye and nobody, including Nagayama’s ex-wife or Otani, discovered he had been hanged until it was leaked to the press days later.

That particular time had been chosen, speculates Otani, because it was around the time of a horrific murder, carried out by a juvenile, in which the body was amputated. To execute a convicted murderer then – even one who was as famous, and whose death sentence was as contentious as Nagayama’s – “would not have drawn much public criticism”.

Otani was given the task of collecting his remains – which included a metre-high manuscript of “novels that would never be read” – and carrying out his final wish, declared directly before his execution: that this future royalties were given to “the poor children in the world, especially those in Peru”.

During his time on death row, Nagayama continued to educate himself, and in doing so came across a news story about an organisation called MNNATSOP (the national movement for working children in Peru), which was working to improve the lives of child labourers in Peru. Learning about the plight of these children who, like him, lived in extreme poverty with a childhood often defined by neglect, violence and malnourishment, moved him deeply. He empathised with their struggles for recognition and resolved to help how he could. Six months later, he was dead.

Otani was part of a team of Japanese representatives who travelled to Peru in 1997 to meet with MNNATSOP and carry out Nagayama’s final wish. By the autumn of that year The Nagayama Children Fund was created and used to help found Infant Peru – the working children’s training institute – donating enough money for the organisation to purchase a house to use as both an office and temporary accommodation for young people in need.

Today, Peru is thought to have the highest level of child labourers in South America (21 per cent of children over five) and since 2004 the fund has been used to finance the organisation’s higher education scholarship, donating around 24 million Japanese Yen (£157,000) to date.

By offering higher education to those who would not otherwise be able to afford it, more young people have more options than simply working “in whatever [jobs] are available in vulnerable circumstances,” says Esther Dìaz, director of Infant Peru. “It also endows them with a level of social and political conscience, [to be] fighters for the rights of children and teenagers in decision-making positions of the state.”

The fund has so far enabled more than 300 children to receive a higher education, such as Jesus Fernandez, who was able to resume the engineering studies he had been forced to quit due to economic hardship. The fund, he says, has enabled not just economic but psychological support; something he hopes will continue for generations to come.

Annie Olivares, 20, was also granted a scholarship to attend Lima College and achieve her goal of becoming an English teacher. Today she promises to “return what I have received by providing support to others in the future”.

While Nagayama and his work was not always well-received – the Japanese Writers Association, for instance, rejected his request to join in 1989, “given his status as a convicted killer” – this has not been the case at Infant Peru, where his framed photograph hangs on the wall, and his ink pot and pen is preserved in a glass display case.

“Despite a life defined by poverty and marginalisation,” says Dìaz, “Nagayama put himself at the service of the most underprivileged young people of Peru. Today, he lives on with dignity, in each of them.”

Nagayama has a legacy in Japan also, with organisers behind the fund holding commemorative events on the anniversary of his execution every year, including forums and panel discussions on how to move the abolition movement forward.

While these events receive some media coverage, and two new groups (led by former government ministers) have recently joined the movement, Otani admits she is still pessimistic about any progress in the immediate future. It’s unlikely that Japan will abolish the death penalty unless the US does first, she says, and Japan is thereby “forced to by rising international pressure. And this is true of Japan's human rights policy in general,” she adds.

Dr Mai Sato, associate professor at Monash University and director of Eleos Justice, also agrees that capital punishment will likely be retained in Japan unless doing so puts a genuine strain on the country’s international relations. “Japan and Australia are currently negotiating a ‘reciprocal access agreement’, allowing military operations in each other's territory,” Sato explains. “But they haven’t managed to reach an agreement for the last six years because of the Japanese death penalty.

“This is an opportunity for the JFBA to send a strong message to the Japanese government,” says Sato; that by retaining the death penalty, they are jeopardising diplomacy and military agreements. But to date, “they have not been willing to do that”.

I’m a little ashamed to admit that until I was a student in the UK, I had never paid attention to the death penalty…

The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) is the official body for all practicing lawyers in Japan; in 2016 it voted to become an abolitionist organisation, which – considering its status – was thought to be a huge step forward in the movement. But in the four years since taking this stance, says Sato, they seem to have done little more than hold discussions, rather than taking real action. If more middle-level organisations with some power – for instance official bodies in the medical and academic realms – came together to voice opposition to the death penalty, she adds, there might be more hope for the movement to progress.

But with Japan being the only major industrialised democracy alongside the US to retain capital punishment, and with the ongoing Iwao Hakamada case demonstrating the huge scope for miscarriages of justice that it entails, why is there not more opposition from the public?

“Because it’s simply not something Japanese people think about on an everyday basis,” says Sato. “I'm a little ashamed to admit that until I was a student in the UK, I had never paid attention to the death penalty… if I never left Japan, I’m pretty sure I would have been one of those survey respondents who said, ‘Yeah, I guess the death penalty is unavoidable’.”

The survey Sato refers to is the government’s public opinion poll, which canvases opinion on capital punishment every five years. The most recent one, in 2019, showed that 80 per cent of respondents felt the death penalty was unavoidable. In 2014, the figure was exactly the same.

This is a huge barrier to the abolition movement, explains Sato: “When the Japanese government reports to the UN Human Rights Committee on why they haven't abolished the death penalty, they cite ‘public support’, as well as the continual existence of heinous crimes.”

Through her films Sagakami also tries to encourage viewers to question not just the death penalty, but the social factors that contribute to crime itself

However, in her 2015 report, The Public Opinion Myth: Why Japan retains the death penalty (written along with Dr Paul Bacon), Sato’s research demonstrated that public support may not be as overwhelming as it seems.

Yes, 80 per cent did agree with the statement, “the death penalty is unavoidable”, but further analysis of respondents’ opinions revealed that only 34 per cent could be considered what Sato calls “committed retentionists”, ie those who felt capital punishment was unavoidable, and also did not agree with replacing it with life imprisonment without parole, and also would not accept the possibility of future abolition.

This, Sato argues, is a far lower number than the “80 per cent” that gets so frequently touted, and strongly calls into question the government’s claim that abolition would undermine the criminal justice system’s legitimacy.

The continual existence of heinous crimes is questionable. “Japan’s murder rate is actually very low,” says Hirohiko Katayama, a volunteer at Amnesty International – around 0.3 victims per 100,000. Nonetheles, citing research by David Johnson, Katayama claims that the Japanese media tends to sensationalise and exaggerate the frequency of serious crimes, while playing down its low homicide rate, creating a sense that Japan is perhaps “not so safe after all” and the death penalty is needed, as a deterrent. (Almost half of the 2019 poll respondents felt violent crimes would increase if the death penalty was abolished).

Documentary maker and lecturer on the death penalty, Kaori Sagakami, agrees that the media represents a skewed image of criminals. “There are about 100 death row inmates, very few of which get any media attention,” she says. “The ones that do are demonised, and there’s a general sense that the others must be the same,” she adds, citing the example of one death row inmate she befriended, who has recently been executed.

There was “no truth” in the media portrayals of him as a “monster”, says Sagakami. Even the particulars of the crime he was convicted of (while a minor) were inaccurate. At least Nagayama was able to tell his story, she adds. Her friend, “never had a chance”.

This lack of transparency around who is on death row, and why, is accompanied by a general lack of knowledge around what the system entails. Sato’s research, in which she conducted a survey parallel to the government’s, revealed that only 51 per cent of the public knew that inmates are executed by hanging.

Add to this that very few people in Japan are directly impacted by prison life (there are less than 50,000 prisoners in Japan today in comparison to the US’s 2.1 million) and you also have a sense of apathy towards criminals, says Sagakami. “They are ‘other’. It is us and them.”

And this is perhaps the main factor behind retention: until much more of Japan’s society starts to see their country’s penal system as something deserving of critical attention, there is little hope for any real change. Key to this, say all three abolitionists, is education.

“That’s one reason why at CrimeInfo [an NGO promoting the abolition of Japan’s death penalty, co-directed by Sato] we’ve developed a textbook on the death penalty, to provide [teaching] guidance for high school, junior high school and even university lecturers,” says Sato, adding that there has been a steady stream of requests from teachers to download the death penalty materials. “So there’s definitely some appetite [to know more] there,” she says. “And when the schools do contact us, we get good feedback that it's something that students have never thought about before.”

Through her films Sagakami also tries to encourage viewers to question not just the death penalty, but the social factors that contribute to crime itself. Her latest film, Prison Circle, is the first theatrical documentary film to be made behind prison walls, and in the year since its release has received more attention, positive feedback and sparked more debate than any of her previous films (which are based in the US).

So while the abolition movement may not have moved on much in the three decades she has been a part of it, she says, this reaction at least suggests that Japan’s younger generation want to “question things more. And that,” she adds, “is a very good sign.”

Translation by Hirohiko Katayama and Ed Neidhardt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments