A lightning strike fried her nerves and melted her skin – the damage will last years

The 950 million volts fried Amber Escudero-Kontostathis’s nerves, melted her skin and stopped her heart. But the lone survivor tells herself, ‘I’m the lucky one’, writes William Wan

She wakes up, like most mornings, in pain.

As Amber Escudero-Kontostathis lies in bed, it feels like someone is taking a razor-thin scalpel and delicately slicing into her legs.

The 28-year-old fundraiser eases into her fuzzy black-and-white slippers to get ready for a doctor’s appointment, and with each step, her feet feel like giant blisters threatening to pop under pressure.

“Sometimes, the slightest thing will set them off,” she says, gingerly tapping her foot.

It has been 174 days since lightning struck a tree across from the White House, where Amber and three others were sheltering from the 4 August storm.

She was the only one who lived. Her doctors called it a miracle that she survived the millions of volts of electrical current that coursed through her body.

The lightning strike blew up her electronic tablet. It made her watch so hot, it melted flesh on her wrist. Surging up through her foot, it fried her nervous system, stopped her heart and burned gaping holes in her body. For days, she couldn’t move. She had to relearn how to walk.

Her emotional recovery from the trauma has been equally daunting. She has been plagued with guilt for surviving when the others – a couple celebrating their 56th wedding anniversary and a young banker from California – did not. Guilt for not thinking of them as soon as she woke up every morning in her Washington DC apartment. For not being anything other than grateful on days when she felt angry and exhausted.

She has worked through so much in the months since. But the pain remains. In the middle of the night, she startles her husband, Achilles, yelping in her sleep and grabbing at her feet.

A doctor specialising in nerves told her that six months would be an important milestone. After six months, it can be harder for some nerves to recover, he said. For some patients, the pain becomes a chronic, permanent condition.

“That was scary to hear. To imagine living with this the rest of my life...” her voice trails off as she arrived that morning at the nerve expert’s office in the Maryland suburbs.

She is now five months and three weeks into her recovery, and she is worried what the doctor will say.

Sitting in the waiting room, her body is still going haywire. Her right leg feels cold and wet, like someone pouring a bowl of cold water over it.

“How are you doing?” the nerve specialist, Alexander Kiefer, asks as Amber walked into the exam room.

“Good,” she answers reflexively.

But when Kiefer presses her on what she had been feeling lately, Amber lists a slew of bewildering sensations.

There is the grinding pain, like sand grains trying to squeeze through the pores of her skin. Burning and freezing sensations that strike at random. Itching in her wrist. Piercing needles in her toenails and bruising bone aches. And the strangest one of all, a twisting in her right foot – where the lightning entered her body – like a mechanical gear constantly spinning inside her ankle.

“Everyone’s been optimistic,” she says. “But I just want to know if any of my nerves are, like, dead-dead. Like not coming back. Is there any way to test that?”

“It’s still early,” the doctor says gently.

The six-month marker, he says, was not a hard-and-fast rule – more of a checkpoint. Some recoveries take longer. He mentioned soldiers he had treated with bullet-riddled spinal cords who were still recovering new feeling and function years later.

“There’s still a lot of hope that you can continue to improve,” he says.

As Amber slowly walks back to the car, where her husband is waiting, she is determined not to let the disappointment consume her.

“How’d it go?” Achilles asks. He had seen her nervousness going in.

“Fine,” Amber says. “He thinks I’m making progress.”

She tells him about the soldiers still recovering years later. “I know he was trying to make me feel better, but it did the opposite,” she says.

How much more pain and uncertainty could she endure? She didn’t know.

The earrings she was wearing that day – charred black – lay in a plastic container near her bed. Her tablet sat in the closet, jagged cracks on its screen. Nearby was a frayed lanyard from her work badge that paramedics cut off her body. All reminders of a day she still can’t remember.

It happened on her 28th birthday.

She can recall her co-workers surprising her that morning with vegan doughnuts as they prepared for another day of fundraising for the International Rescue Committee.

Amber was one of the non-profit’s most successful canvassers, securing donations for Syrian refugees from strangers on the street with her sunny personality and insistent belief that people genuinely care for others. She often stationed herself at Lafayette Square, the historic park across from the White House – an area rich with internationally-minded government workers and tourists from all over.

It had been hot and humid that August day, but toward the end of her shift, the sky began thickening with clouds. In her last text that afternoon, she sent a picture to her sister-in-law of the approaching storm.

“Went from feeling like 105F [41C] all day,” she wrote at 5.44pm “Now here comes thunder.”

When she tries to remember what happened next, her mind goes blank.

Witnesses would later compare the crashing boom to an exploding bomb. Scientists would record six distinct bolts of lightning hammering a single spot in the space of half a second.

Their instruments would measure an electrical current of roughly 950 million volts. All surging into the tree, down through the ground and back up the bodies of the four bystanders.

When lightning strikes, the current’s path is random. A negative charge built up in the clouds reaches down, searching for a corresponding positive charge on the ground. The giant spark that unfolds is the meeting of those two forces – so powerful it turns rain and sweat to steam.

Experts estimate that the chances of an individual being struck by lightning during his or her lifetime at roughly one in 19,000. One out of every 10 people struck die, with about 22 US fatalities a year.

For those who survive, the most devastating injuries are often internal, says Mary Ann Cooper, a physician at the University of Illinois at Chicago who has researched lightning injuries for four decades.

“The electricity can go in and out without leaving a mark,” she says. “But the damage to their nerves and brain can be extensive.”

Amid the pain that follows, some lightning survivors fall into despair.

“I’ve talked more than 20 people out of suicide,” says Steve Mashburn, 78, who runs an international support group for lightning survivors. In 1969, lightning struck his bank teller window in North Carolina. The electricity coursed through the speaker system into his body and broke his back, resulting in 49 surgeries.

Like many survivors, Mashburn suffered inexplicable symptoms: migraines, insomnia, kidney problems, panic attacks and seizures. Even now, five decades later, Mashburn says, “I’m thirsty all the time. I can never get enough to drink.”

Some people lose their jobs, health insurance, marriages, says Mashburn, whose group includes more than 1,800 members worldwide. “You try to explain what you’re experiencing, but people don’t understand or they think you’re crazy.”

After the Lafayette Square strike, Amber woke up at MedStar Washington Hospital with no idea why she was there.

Her family shielded her at first from what had happened. But as she regained her ability to talk, she began piecing it together. On an iPad, she read every account she could find of the lightning strike.

Eventually, she found a video of paramedics giving her chest compressions as they wheeled her into an ambulance. “They were putting so much force on me. They were practically jumping on my chest,” she says.

The Secret Service agents who reached Amber first said her skin was dark purple and grey, and her mouth strangely locked open. They had small defibrillators but couldn’t get them to work in the rain. A doctor from the White House and two passing tourists who work as ER nurses kept her alive with CPR.

The first time they resuscitated her in the park, Amber recovered just long enough to squeeze one nurse’s hand and lock eyes with an agent. Then her heart stopped again for 13 minutes. But because of that squeeze, they told her later when she met with them, they didn’t give up.

She talked, as well, to the families of those who died.

“It felt important to know who they were and what they meant to the people who loved them,” she says. “So that I can carry them with me.”

Amber spoke for more than an hour with the boss of Brooks Lambertson, 29, a bank vice president from Los Angeles. She was also struggling with survivor’s guilt, for arranging the business trip that had brought her and Lambertson to Washington, for deciding with him to walk past the White House on their way to dinner, for escaping unscathed while Lambertson was killed.

The rescue workers reassured Amber that they had tried just as hard to save the others – that it wasn’t because of their focus on her that the other three had died. But she couldn’t help feeling responsible.

She talked to the children of Donna Mueller, 75, a retired teacher, and her husband, James Mueller, 76, who had come to Washington from Wisconsin for their wedding anniversary. Seeing their photos, Amber realised she had met them earlier that day, before the storm. She remembered telling Donna that her mum was a teacher, as well. Amber had taught them how to stick their hands through the White House fence to get an unobstructed photo of the mansion.

“They were such a sweet couple,” she says.

Their children told her how James often brought Donna coffee in bed, so Amber made a point of thinking about them whenever her husband made her a cup of coffee. They loved the colour red, so Amber surrounded herself with comfy red cushions as she recovered.

“Whatever I’m experiencing that day, however much pain I’m in, I try to hold on to the fact that I’m the lucky one,” she says. “The one who gets to feel anything at all.”

She received bizarre emails from strangers, implying there was some bigger reason she had survived – the intervention of some supernatural power, of fate or destiny.

But as time passed, Amber came to see it differently.

“I didn’t survive because of a miracle,” she says. “I survived because good people, complete strangers, ran toward danger in the middle of a storm to save me.”

On some days, that realisation was a source of inspiration, a calling to keep recovering so she could do the same with her own life. On other days – when she was in so much pain she fell asleep sobbing – it felt impossible.

When she left the hospital a week after the strike, the doctors sent her home with a thick metal walker and instructions not to practice walking more than 10 minutes twice a day.

Amber struggled with the uneven sidewalks around her apartment. So she convinced her husband and her mum to take her and her dog, Astro, to the smooth walkways by the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial near the Tidal Basin.

It was a gorgeous autumn day, not a cloud in sight.

Amber felt great, so she kept walking – 30 minutes passed, then 45, then 90. Suddenly, recovery seemed not just possible but actually happening.

By the time she arrived home that night, however, it felt like someone was repeatedly setting her feet on fire then plunging them into a mountain of snow.

For the next two days, she couldn’t move. To get her to the bathroom, Achilles and her mom had to cover the floor with pillows, stand on either side of her and delicately slide her back and forth.

The lightning left intricate red ferning marks on her chest, like the roots of a tree.

The worst burns were on her stomach and thigh, where her tablet had been pressed up against her body. There were gaping white wounds in her skin. To prevent infection, she had to sit in the shower for three hours every day, scrubbing deep into the oozing holes so they could be dressed with ointment and gauze. She watched with disgust and fascination as the holes slowly filled back up with skin, pores and hair.

At the request of her doctors, she began measuring her pain on a scale from one to 10. Even on her worst days, she refused to call it a 10. “Ten means I can’t handle it,” she says. “I told myself I can get through anything as long as it’s not 100 per cent of the time.”

Her suffering, at first, was so intense she spent hours simply screaming. She taught herself to follow each scream with a whisper, “But I’m grateful”.

She came to see gratitude as an antidote to her agony, as well as the depression and the fleeting suicidal thoughts she experienced early on.

She realised that the pain existed primarily in the mind. Yes, there were physical components to it. Electrical signals running from her skin, up her spine to her brain. But there was an emotional aspect as well, that depended on her perspective.

The doctors initially had her taking so many medications that her husband started calling the pill organiser they lugged around “the pharmacy.” Lyrica, oxycodone, nadolol, hydroxyzine, Cymbalta, gabapentin. He wrote out an hourly schedule to keep them all straight.

It was harrowing to see her struggling, says Achilles, 29, who works as a data analyst for a digital start-up.

When they met at Pepperdine University in California, it was Amber’s bubbly personality and her passion for helping others that drew him in.

“I was a typical frat guy,” he says, “focused on party mixers, rugby and finance.” Amber opened his eyes to the people suffering in other parts of the world. They got married right after college, moved to the Middle East and started a non-profit organisation together, working with children and refugees.

Now, as Amber’s nerves healed, the only way they could judge her progress was by periodically taking her off the painkillers and measuring how she felt. On three occasions, Amber’s doctors operated on her – a nerve-block procedure that injected lidocaine into her spine to temporarily numb her nerves. They hoped it would act as a reset for her nervous system, like unplugging a computer and plugging it back in.

In preparation for her third nerve-block operation this past winter, she weaned herself off all medication – a hard-won victory that took weeks. She cried after the procedure, amazed to find herself completely pain-free.

“I thought, ‘This is it. It’s finally over,’” she says. “Then, the pain came rushing back, and we realised it was just the anaesthesia wearing off.”

Her heart now beats faster when it rains. She checks the weather app on her phone constantly. This winter, on a trip to New York with her parents, she was in line at the 9/11 Memorial Museum when thunder rumbled across the sky.

“I started gasping for air and broke down into a full-on panic,” she says.

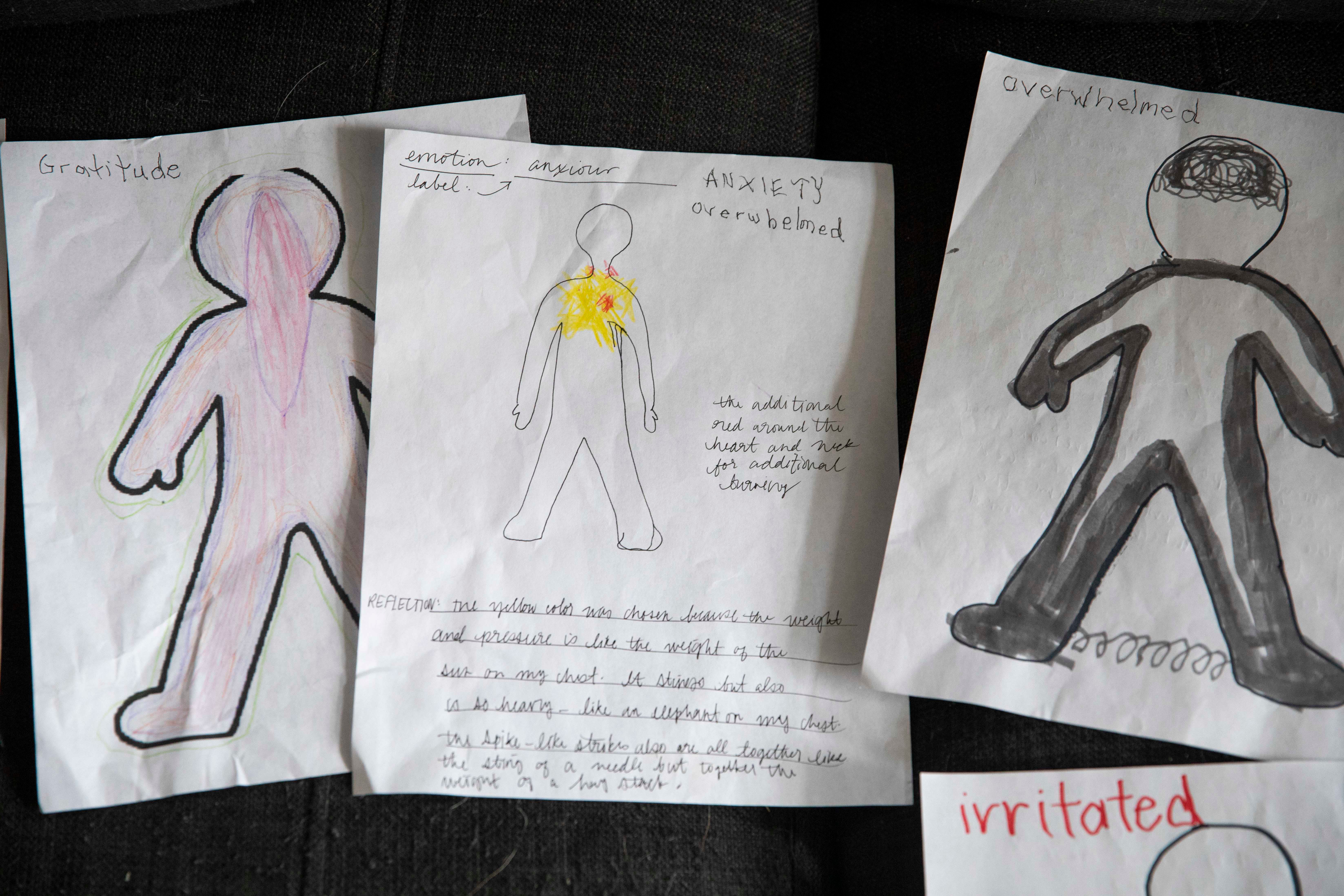

She was still meeting once a week with a psychologist from MedStar’s burn unit. The therapist told her to draw her feelings on paper. So Amber filled in a cartoon outline of her body with heavy grey marker and shackles around her legs. “My body feels like it’s weighed down by metal,” she told him.

Ever since she watched that video of paramedics doing CPR on her, she had been experiencing asthma attacks. With little warning, she would feel like an elephant was sitting on her chest.

But the hardest thing about her new life wasn’t physical.

“I just need so much from Achilles, from my parents,” she says. “All I do now is take, when the thing I’ve wanted to do my whole life is give to others.”

It’s why, at age six, Amber’s mum found her crying late at night after she saw a TV ad about children starving in Africa. It’s why she majored in international studies and moved to the Middle East to teach refugee children. It’s how she came to be a fundraiser, convincing people to give money to others a world away.

It was brutal work. For every 100 strangers she approached, usually only 10 stopped to talk. Of those 10, only one would donate.

“People are always in a rush to get to work or home or into their routines,” she says. “But if you can break through that, you see that they do care. Every ‘yes’ I get restores my faith in humanity and washes out the 100 ‘nos’.”

In her first year of fundraising, the canvassing team she led became one of the International Rescue Committee’s most successful, signing up 3,400 monthly donors for a total of more than $1m a year.

After the lightning strike, she could no longer stay on her feet long enough to canvass, but she returned to work in November, to manage her non-profit’s regional team of fundraisers.

On days when she wasn’t tied up with work or doctor appointments, she was taking classes. For seven years, she had dreamed of attending the graduate programme at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. She hoped to earn a Masters degree, become proficient in Arabic and somehow contribute to peace in the Middle East.

Last summer, before the lightning strike, she found out she was accepted.

So when the first semester began – three weeks after her release from the hospital – she begged her doctors and family to let her attend as a part-time student.

“I think they realised that in the face of my depression and anxiety,” she says, “it was better that I had something to do, as crazy as it seemed.”

She hobbled to class on her walker. She was still on so many painkillers that she struggled to take notes. She bought medical-grade sunglasses because the fluorescent lights caused massive headaches.

She finished her two classes, but she hated the constant questions and fascination brought on by her gear and ailments. Every time she had to explain to a classmate how she had been struck by lightning, she felt it all over again. The elephant on her chest. The pain that left her screaming at night.

“I don’t want to be known as the lightning girl anymore,” she says. “I just want to be me again.”

On the night before her second semester started in January, she lay awake in bed until 3am – nervous and excited. This time, she would be able to attend class without her walker. No one would know what had happened to her.

That morning, she kissed Achilles as he dropped her off at a corner of the campus and hurried to her first class: “Conflict in the African Great Lakes”.

She can walk quickly now, even jog at times, but it remains an exercise in trust.

“I still have no feeling from the lower part of my back to my upper thigh, so I can’t sense where my legs are going,” she says. “It’s like I’m floating on a box on my tailbone. I feel pressure pushing up on the box, but nothing else.”

She sits down near the back and introduces herself to classmates in her row. She talks about the refugees she wants to help, her goal of contributing to a peaceful two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She doesn’t say anything about the lightning.

“It went so well,” she says afterward, laughing with relief. “Like I’m normal, just any other student.”

To do the coursework with a sharp mind, she was staying completely off painkillers. But it meant living in a constant state of low-grade agony.

Later that week, at a rehab appointment at MedStar, Amber told her physical therapist that the strange sensations were still there. The twisting gear in her right ankle. The non-existent cold water running down her right thigh.

Her physical therapist, Lisa Saladino, brought out a full-length mirror and told Amber to sit with her legs straddling it. From the mirror’s left side, Amber watched as Lisa ran fingers up and down both legs.

“We’re retraining your brain to feel the same thing in the right leg as the left,” Lisa asks. “You feeling that?”

Amber nods and laughs. “It’s so weird that this helps.”

Her pain level on most days, she says, still ranges from two to five, but her relationship with it has changed. Pain now means she’s getting better. It means her nerves are alive and trying their best to speak to her again.

She doesn’t know if she will ever be pain-free, but the prospect no longer sends her into despair. “It’s not going to stop me from what I’m supposed to do,” she says.

At the end of their rehab session, Lisa has Amber stand on a balance board to see how long she can last without falling over.

“Now try it with your eyes closed,” Lisa says.

“Augh!” Amber says, tipping over.

She takes a breath. “Wait, I can do it. Just lemme try again.”

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments