‘Joker’ reveals a lot about censorship in 2019, but Joaquin Phoenix’s character almost didn’t exist at all

Over 60 years ago, a book claimed Batman and Robin were lovers, Wonder Woman was a lesbian and Superman gave children unrealistic expectations. It almost killed the superhero industry, writes David Barnett

Todd Phillips’ movie Joker, with Joaquin Phoenix in the starring role, has become the most profitable comic book movie in history. Some people said the violence was too graphic. Others were concerned that the story of a powerless, battered, rejected white man who solves his problems with a gun was not the sort of story that we needed in 2019.

And then there were those who called for the film to just be banned. Of course, people say a lot of things, especially on social media.

But moral panics, whether born out of liberal discomfort or conservative rage, are nothing new, and many forms of popular culture have indeed been banned, or withdrawn, due to public pressure, disquiet on the part of the creators about how those pieces of art are being viewed, or from various bodies and authorities charged with being the arbiters of good taste.

Sometimes movies are banned because of regional considerations… 60 years ago Ben Hur was not shown in many Arab states because actress Haya Harareet was an Israeli. More generally, 1974’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was banned in several countries because of its graphic violence, and The Last Temptation of Christ in 1987 was withdrawn in many territories on grounds of blasphemy.

It’s not just movies, of course. Last month saw the annual Banned Books Week, which highlights cases suppressed literature around the world and which is described as an awareness campaign “for radical readers and rebellious writers of all ages to celebrate the freedom to read”.

It was launched in the US in 1982 by the American Library Association (ALA) and Amnesty International, and, according to the ALA, 11,000 books in the US have been banned, withdrawn or “challenged”, many from school or college libraries after complaints from concerned parents.

In recent years they’ve included Cecily von Ziegesar’s Gossip Girl series, Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight, Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, and John Green’s The Fault In Our Stars… all of which have been made into successful TV series or movies.

Censorship and banning is a complex business in the 21st century, and whether it is a good or bad thing often depends on your politics. The right often leads righteous campaigns to ban subversive art, which is attacked as censorship by the left. The left is prone to “no-platforming” public speakers of an idealogical bent with which they disagree, leading to calls from the right of over-sensitive snowflakes bent on curtailing free speech.

The Joker movie probably has the dubious privilege of upsetting everybody at the same time – too much violence, too much excusing of the behaviour of a white, alienated incel-type.

However, it’s something of a miracle Joker was made at all, or that we’ve even heard of the character. It could easily have been that we’d never had a Joaquin Phoenix Joker, nor a Heath Ledger, nor a Jack Nicholson, not even a comical Cesar Romero Clown Prince of Crime from the 1960s Batman series. Not if a psychologist named Fredric Wertham had got his way 65 years ago, when he published a book called Seduction of the Innocent… a book which nearly killed the entire comic book industry.

Wertham was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1895, and moved to America, becoming a US citizen, in 1922. He worked at a hospital in New York where many of those accused of violent crimes were assessed, and he often gave evidence in trials. After the Second World War, he opened a clinic in Harlem that specialised in the psychiatric treatment of poor black teenagers.

During this time it came to Wertham’s attention that comic books were incredibly popular with children. He categorised them all as “crime comics”, whether they were indeed the big-selling crime stories, or horror, which was having a renaissance in the 1950s, or, indeed, superheroes.

And what he saw, he didn’t like. In fact, Wertham was convinced that comics were having a detrimental effect on the collective psyche of America’s youth. So he wrote Seduction of the Innocent, which was published in 1954.

Chief among the publishers targeted by Wertham was EC Comics, which put out anthology horror comics such as Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, and Haunt of Fear, each with a “horror host” such as the Old Witch or Crypt Keeper introducing short, punchy tales with a twist and usually copious amounts of gore.

The Scottish comic book writer Grant Morrison, in his treatise on the history of comics Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero, writes: “However, it wasn’t just EC’s often tasteless horror stories that fired Dr Wertham’s rage; almost inexplicably it was the innocent, floundering superhero titles that really got him foaming. Like any good predator, he could sense their weakness and knew that no articulate voice was likely to speak up as comic books’ advocate.

“If an ‘expert’ like Wertham said they were pornography, then they were pornography. With little to offend anyone in the content of these comics, Wertham was forced to dig deep into an ever-fertile loam of subtext in order to justify a fevered one-handed attack that was conducted with the same brutish, ignorant disregard for the truth that was said to characterise America’s enemies.”

A child can accept all kinds of weird-looking creatures and bizarre occurrences in a story because the child understands that stories have different rules that allow for pretty much anything to happen. Adults, on the other hand, struggle desperately with fiction, demanding constantly that it conforms to the rules of everyday life

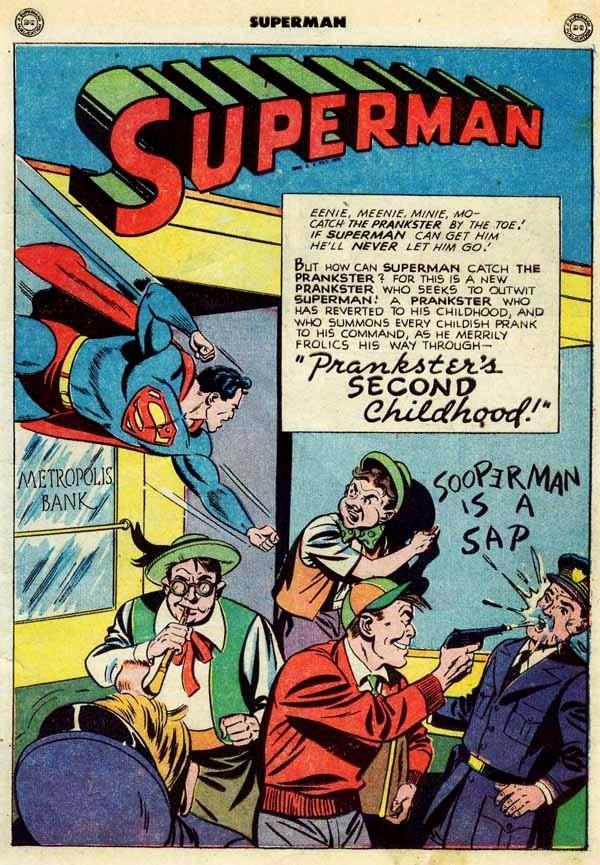

Morrison calls superhero comics floundering because they were; in the early to mid-1950s they were in one of their slump periods, that would not really lift until the early 1960s. However, the main vanguard of characters such as Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman, published by what we know today as DC Comics but was then called National, had enduring popularity… and all fell into Wertham’s sights.

Essentially, Wertham’s arguments about the unsuitability of superhero comics amounted to his assertions that Batman was a paedophile, with sidekick Robin the under-age focus of the Dark Knight’s attentions, that Wonder Woman was a lesbian, and that Superman gave children an unrealistic view of what adults could actually achieve.

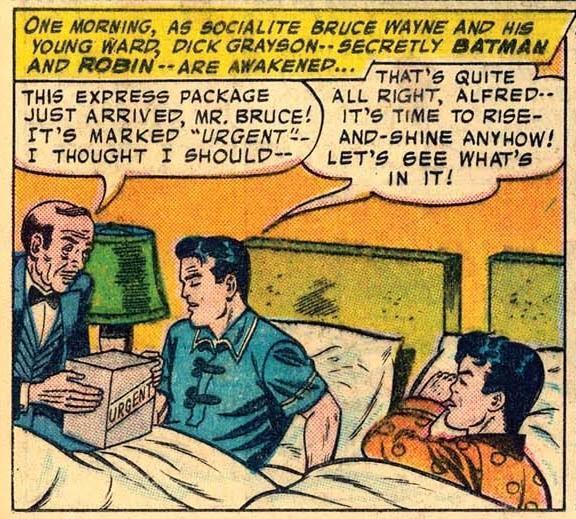

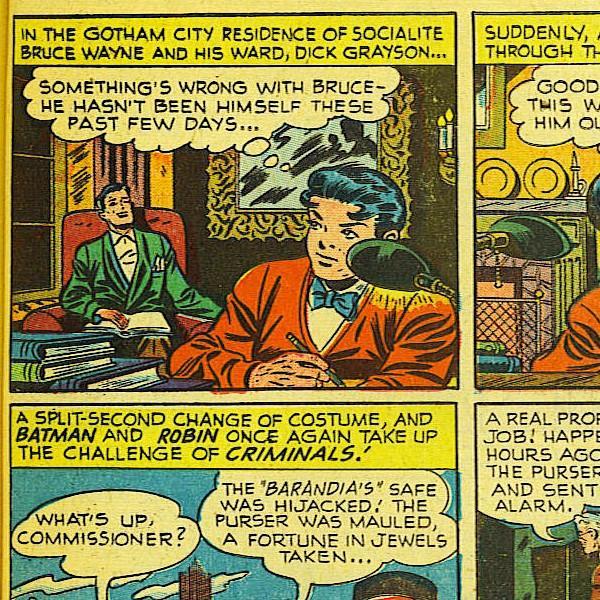

In his own words: “Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and the psychopathology of sex can fail to realise a subtle atmosphere of homoeroticism which pervades the adventures of the mature Batman and his young friend Robin… Sometimes Batman ends up in bed injured and young Robin is shown sitting next to him. At home they lead an idyllic life. They are Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson. Bruce Wayne is described as a ‘socialite’ and the official explanation is that Dick is Bruce’s ward. They live in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases, and have a butler, Alfred. Batman is sometimes shown in a dressing gown… it is like a wish-dream of two homosexuals living together.”

He voices similar misgivings about Wonder Woman, living on her all-female Paradise Island. Wertham writes that Wonder Woman and the idea of female superheroes “is always a horror type. She is physically very powerful, tortures men, has her own female following, is the cruel, ‘phallic’ woman. While she is a frightening figure for boys, she is an undesirable ideal for girls, being the exact opposite of what girls are supposed to want to be.”

As for Superman, the Nietzschean fascistic overtones are obvious, as is the sense of inadequacy Krypton’s most famous son might encourage among parents whose kids read the adventures of Clark Kent’s alter ego. Wertham writes: “How can they respect the hard-working father or teacher who is so pedestrian, trying to teach the common rules of conduct, wanting you to keep your feet on the ground and unable to even figuratively fly through the air?”

The Comic Book Legal Defence Fund (CBLDF) was set up to help comic book creators in America fight court cases where their work was deemed unsuitable and withdrawn or even seized by authorities, and to challenge graphic novel banning. The CBLDF is in little doubt what they think about Wertham and his book: “Seduction of the Innocent was a work of junk science that vilified horror, crime, jungle and superhero comics. Wertham asserted that comics were a corrupting influence on youth and a leading cause of juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s ‘science’ was based around the habits of at-risk youth, lacked a control group, and did not account for the habits of adult comic readers.

With little to offend anyone in the content of these comics, Wertham was forced to dig deep into an ever-fertile loam of subtext in order to justify a fevered one-handed attack that was conducted with the same brutish, ignorant disregard for the truth that was said to characterise America’s enemies

“Chock-full of specious claims and unscientific conclusions, Seduction remains infamous for the assertions that Batman and Robin were involved romantically, Superman was an anti-American fascist, and most egregiously, the conclusion that crime comics were teaching children how to commit violent and evil acts.

“Wertham’s assertions against the medium prompted brutal censorship and lasting stigma against comics.”

That’s because Seduction of the Innocent wasn’t just some dry child psychology textbook that was only of interest to the psychiatric community. It became a national bestseller, and terrified parents who believed their children were enmeshed in a fantasy world that they couldn’t distinguish from real life.

Morrison says: “I tend to believe the reverse is true, that it’s adults who have the most trouble separating fact from fiction. A child knows that real crabs on the beach do not sing or talk like the cartoon crabs in The Little Mermaid. A child can accept all kinds of weird-looking creatures and bizarre occurrences in a story because the child understands that stories have different rules that allow for pretty much anything to happen.

“Adults, on the other hand, struggle desperately with fiction, demanding constantly that it conforms to the rules of everyday life. Adults foolishly demand to know how Superman can fly or how Batman can possibly run a multibillion-dollar business empire during the day and fight crime at night, when the answer is obvious to even the smallest child: because it’s not real.”

But as a response to Wertham’s book, the US government convened the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, and over two days in 1954 put comics on trial. Wertham was the chief witness for the prosecution.

Telling lurid tales of guns, rape and torture, Wertham told the committee: “It is my conviction that if these comic books go to as many millions of children as they go to, that among all these people who have these fantasies, there are some of them who carry that out in action.”

The result was that the committee told the comics industry to get its house in order, or it would do the job for them. The CBLDF says: “Faced with an angry public and the threat of regulation by the government or self-regulation, the comics industry was backed into a corner. They responded by establishing the Comic Magazine Association of America, which instituted the Comics Code Authority, a censorship code that thoroughly sanitised the content of comics for years to come.

“Almost overnight, comics were brought down to a level appropriate only for the youngest or dimmest of readers. Horror, crime, science fiction and other genres appealing to older and more sophisticated readers were wiped out for a generation.”

The superhero comics endured, of course, but the publishers trod carefully. National/DC survived, and paved the way for Marvel in the 1960s. EC Comics all but killed its entire line, save for the humour comic Mad (which, this year, ended its run in print for good).

It’s easy to guess what Fredric Wertham would have made of the Joker movie. Censorship is always a messy debate, with knee-jerk reactions on all sides. It’s understandable that many people think Joker, while starkly reflecting the toxic masculinity of our times, might also encourage or enable it. But Grant Morrison’s thoughts on the matter are telling here… when it comes to comic book heroes and their impact on our society, the kids are generally all right. It’s the grownups you have to watch out for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments