Banned Books Week: How censorship through the decades cracked down on literary sex, drugs... and poo poo head

It’s Banned Books Week, and this year the UK is taking a bigger role in fighting censorship, writes David Barnett

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Consider suppressed books and what do you think of? Someone carefully measuring out the ingredients for a bomb in their mother’s cellar, poring over The Anarchist’s Cookbook? A 1980s Britain supposedly blissfully unaware of the revelations in Peter Wright’s banned MI5 memoir Spycatcher, while the rest of the world laps up his allegations? Well-thumbed copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover being passed surreptitiously between filth-hungry readers?

Or do you perhaps think of the Great Poo Poo Head Incident of 2011?

Allow me to remind you of that one. Back then, Tammy and Randy Harris’s son was six-years-old. He was given a one-day suspension from his school in Texas for deploying with wild abandon the phrase “poo poo head”.

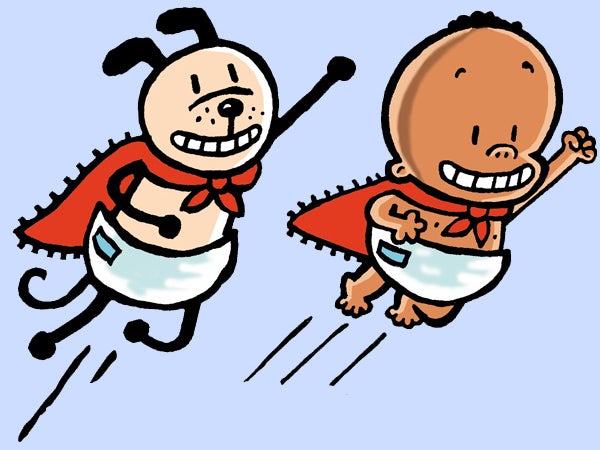

Which might seem a bit harsh. But then Tammy discovered that the self-same epithet uttered by her son was also to be found in a book kept in the school library, to wit The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby, a graphic novel from the same creators behind the hugely popular Captain Underpants series of prose books.

Was it fair that her son was sent home from school for saying “poo poo head” when those exact words were in a book on the school library shelf? So Tammy Harris demanded that the book be removed from the school.

Her demand was rejected at first, but following an appeal and a fresh investigation into the incident, an education committee upheld her complaint and The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby was duly banned from that Texas school.

So when we talk about book bannings, we’re not necessarily discussing Nazi-style bonfires of books… though that still happens. A couple of years ago ISIS torched Mosul library and everything in it. But what is more common are incidents such as the Poo Poo Head one, in which parents take exception to something found in a book their child has procured from school, and immediately try to get it withdrawn from circulation.

It happens a lot in America, of course, and that is why Banned Books Week, which begins on 24 September, has been an annual event since 1982. A loose coalition of anti-censorship organisations band together for the awareness-raising event, and each year the American Library Association releases a list of the “most challenged” books across the States.

By far the biggest reason given for complaining about books is that they have characters who are lesbian, gay, transgender or bisexual, or stories which deal with these themes. And the complaints are not because LGBT characters or issues are dealt with poorly; it’s because they’re there at all.

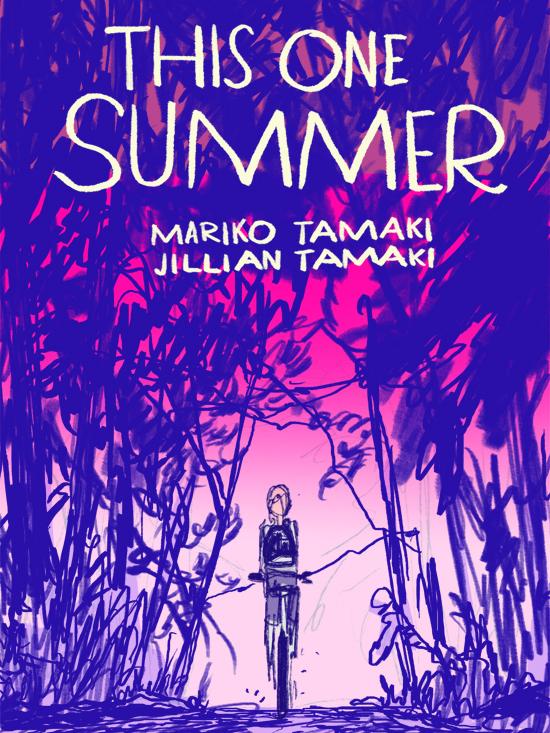

The most-complained about book in 2016 was This One Summer, a graphic novel written by Mark Tamaki and illustrated by her cousin Jillian Tamaki. It’s a coming-of-age story that was frequently challenged, according to the ALA, because of its “LGBT characters, drug use and profanity, and it was considered sexually explicit with mature themes”.

Alex Gino’s 2015 novel George, which features a transgender lead character, was wanted off the shelves because “sexuality was not appropriate at elementary levels”, while The Fault In Our Stars author John Green’s Looking For Alaska was challenged for a sexually explicit scene that may lead a student to “sexual experimentation”.

It isn’t all redneck outrage against non-heterosexual relationships of course, though it mainly is. In the top ten of last year’s most complained about books was the Little Bill series written by Bill Cosby, by dint of the high-profile sexual assault allegations surrounding him.

Banned Books Week takes a Voltairean stance on book bannings; you don’t have to like what’s in the book to disagree with censorship. In 2015 someone wanted EL James’s 50 Shades of Grey banned because it was “poorly written”; well, a lot of people might think that, but it’s not really a reason for it to be suppressed, nor is the fact that it’s full of kinky sex. The good thing about books is that if what’s inside them is deemed offensive, you can’t see it until you open the covers.

We might expect that book bannings are a particularly American thing, but this year Banned Books Week is a bigger thing in the UK than it ever has been before, largely due to the involvement of the non-profit campaign Index for Censorship.

“Censorship isn’t something that happens far away,” says Jodie Ginsberg, the campaign’s CEO. “It has happened in the UK. In every library there are books that British citizens have been blocked from reading at various times. As citizens and literature lovers we must be constantly vigilant to guard against the erosion of our freedom to read.

“Index is excited to be joining the coalition as the first non-US member. We have been publishing work by censored writers from around the world for 45 years and – given all that is happening on the global political stage – it feels more important than ever to be highlighting censorship and demonstrating just what it means when books are banned.”

Charles Brownsein, chair of the Banned Books Week Coalition and executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defence Fund, which finances comic book creators and retailers court cases against censorship actions, is delighted that the primarily US event now has a foothold in the UK. He says, “We are very excited to have the Index on Censorship join the coalition. Their work not only aligns with our mission, but will bring an international perspective and awareness to our annual celebration of the freedom to read.”

There are a series of events taking place this coming week, many of them at the British Library in London, including on Tuesday a talk by Katherine Inglis and Matthew Fellion, authors of a new book on suppressed literature; an investigation into the Salman Rushdie Satanic Verses affair which saw the author go into hiding as his book was burned in Bradford (Thursday) and on Saturday 30 September a look at the controversial novel by JG Ballard, Crash, with Will Self and Chris Beckett, followed by a screening of David Cronenberg’s movie adaptation.

The events show the breadth of work that has been banned, suppressed or called for removal from shops, libraries and schools. According to Lisa Appignanesi, chair of the Royal Society of Literature, “It’s an irony that the list of books banned over the last centuries, whether by religious or political authorities jealous of their power, constitutes the very best of our literatures.

“From the Bible to Thomas Paine, Flaubert, GB Shaw to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, some of the greatest of our books have been banned somewhere. Luckily humans have a way of valuing the prohibited and cherishing liberty; and this as George Orwell reminded us, ‘means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear’.”

So if you’re going to celebrate Banned Books Week, what should you be reading to show your support? Penguin Books has put together a handy list of the books they tried to ban (and in some cases did), and some of them might seem surprising.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by DH Lawrence we’ve already mentioned, and its publication in 1960 led to one of the most famous obscenity law trials in history. But what about George Orwell’s Animal Farm, banned in the Soviet Republic in the 1980s because of its portrayal of a brutal dictatorship. Well, if the cap fits… And then there’s Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the earthy wit and saucy humour of which found it out of favour in 19th-century America.

Pretty much any Roald Dahl book has come under the censors’ spotlights at some point, especially in the States. The BFG was once accused of “promoting cannabilsm”, but it’s The Witches that has proven especially notorious, with complaints levelled at it including that it contains Satanic themes, turns children towards the occult, and doesn’t do a very good job of upholding moral values.

Or maybe you could just track down a copy of George Beard and Harold Hutchins’ The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby, and spend the week shouting “poo poo head” at the top of your voice.

Because as anyone knows, and as Texan parents Tammy and Randy Harris learned swiftly, the moment you call for something to be banned, interest in it rockets. Back in the 1980s, more people were determined to get their hands on Spycatcher than ever bothered reading it just because they’d been told by the British government they weren’t allowed to have it.

As Randy Harris said, appearing somewhat mystified, when the couple were interviewed by US TV channel ABC13 on their successful bid to get Diaper Baby cleared from the school shelves, “Every kid in that school knows about that book. And every kid wants to check that book out.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments