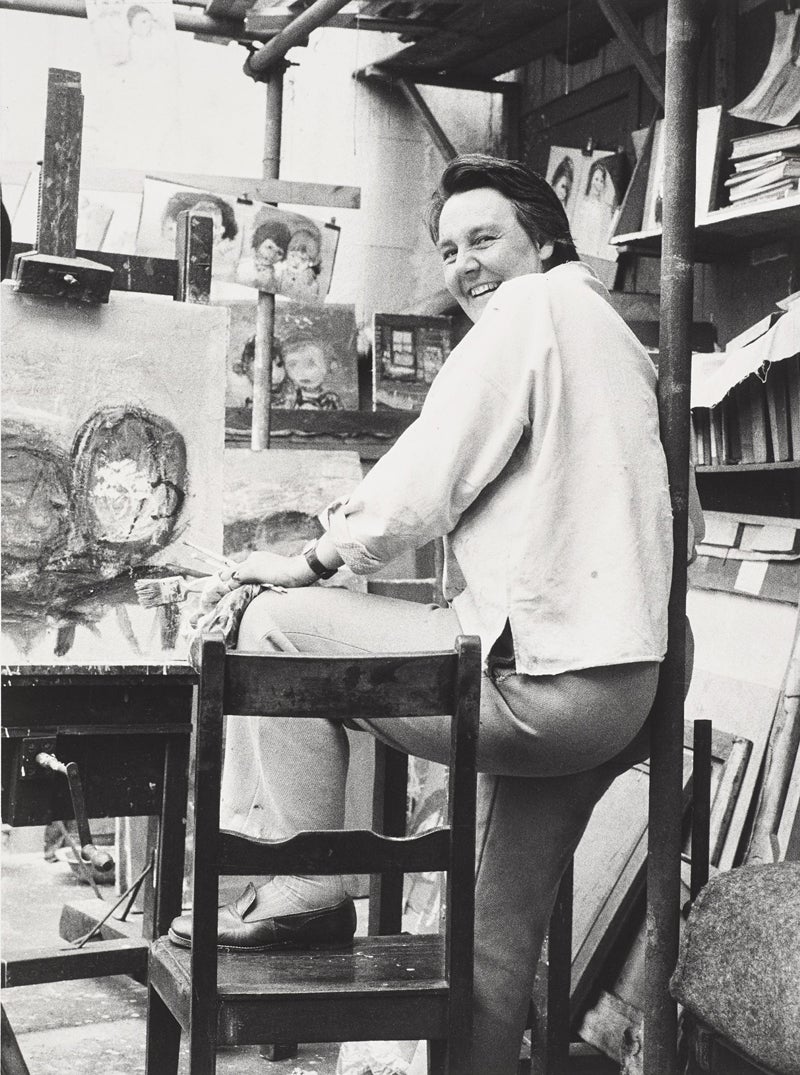

‘In Scotland, she’s huge’: Why was Joan Eardley forgotten by England?

On the 100th anniversary of her birth, William Cook examines Joan Eardley’s huge contribution to the arts, and asks why she isn’t as celebrated in the country where she was born and raised

This summer, art galleries all over Scotland are celebrating the centenary of one of Scotland’s favourite artists, a woman who captured the essence of urban and rural life in her powerful, unsentimental paintings. In Scotland, Joan Eardley is that rare and precious thing – an artist who cuts through. Art historians revere her, but she’s also adored by folk who rarely go to galleries. She’s equally popular with the cognoscenti and the hoi polloi.

“In Scotland, she’s huge,” says Patrick Elliott, senior curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, and the author of an absorbing new book about Joan Eardley. And yet south of the border, it’s a different story. In England, where she was born and raised, it’s hard to find anyone who’s heard of her. You might meet the odd artist or curator who knows (and loves) her work but to most “Sassenachs”, even art-lovers, her name means nothing. It’s the same story overseas. So why do Scots feel such a close connection with her gutsy paintings? And why is she virtually unknown elsewhere?

Joan Eardley was born in Sussex on 18 May 1921. Her father, William, was English, and her mother, Irene, was Scot. William was a farmer and had fought in the First World War on the Western Front. This ordeal left him with severe shell shock and he suffered from depression and when the farm failed he turned to drink. In 1926, William went to Lincoln, to work for the Ministry of Agriculture, and Irene took Joan and her younger sister Pat to London, to live with Joan’s maternal grandmother in Blackheath. Then, in 1929, William took his own life. It wasn’t until she was in her late teens that Joan learned that her father’s death had been suicide.

Joan’s mother wasn’t wealthy, but there was enough family money for Joan and Pat to attend a local private school, where Joan showed a flair for art. In 1939 the Eardleys left London for Scotland, to escape the Blitz. The family ended up in Bearsden, a leafy Glasgow suburb, far enough from the Clydeside docks to avoid the attention of Hitler’s Luftwaffe. In 1940, Joan enrolled at the internationally renowned Glasgow School of Art.

Joan shone at the Glasgow School of Art, winning the prestigious Guthrie Prize for an unusually mature self-portrait. After graduating she went to teacher training college, but she hated it and left after a single term. After two years working as a labourer in a boatyard, she returned to Glasgow School of Art as a postgraduate. This time she won a travel scholarship, which she used to go to Italy, and on her return, Glasgow School of Art exhibited the drawings she’d done abroad. In a roundabout way, it was this exhibition which led her to the rugged location which inspired her greatest paintings.

An art teacher from Aberdeen called Annette Soper saw the show, and invited Joan to exhibit in a makeshift gallery above Aberdeen’s Gaumont cinema. The two women became close friends and toured the surrounding countryside together. They ended up in a little fishing village called Catterline. A cluster of weathered cottages, huddled on a clifftop above the wild North Sea, there was nothing cute or cosy about this windswept outpost, but both women fell in love with it. When they discovered that one of these cottages was empty, Annette bought it for £40. This was the first of several cottages that Joan lived in there in Catterline. From the early Fifties to the early Sixties, she spent much of her time there. It became the forum for her most arresting artworks. She painted it in every kind of weather – in storm and sunshine, rain and snow. “This is a strange, strange place,” she confided in a letter to a friend. “It always excites me.” This excitement runs through all her work.

A lot of artists are only just getting started in their early Forties. We can only guess at all the paintings within her which were left undone

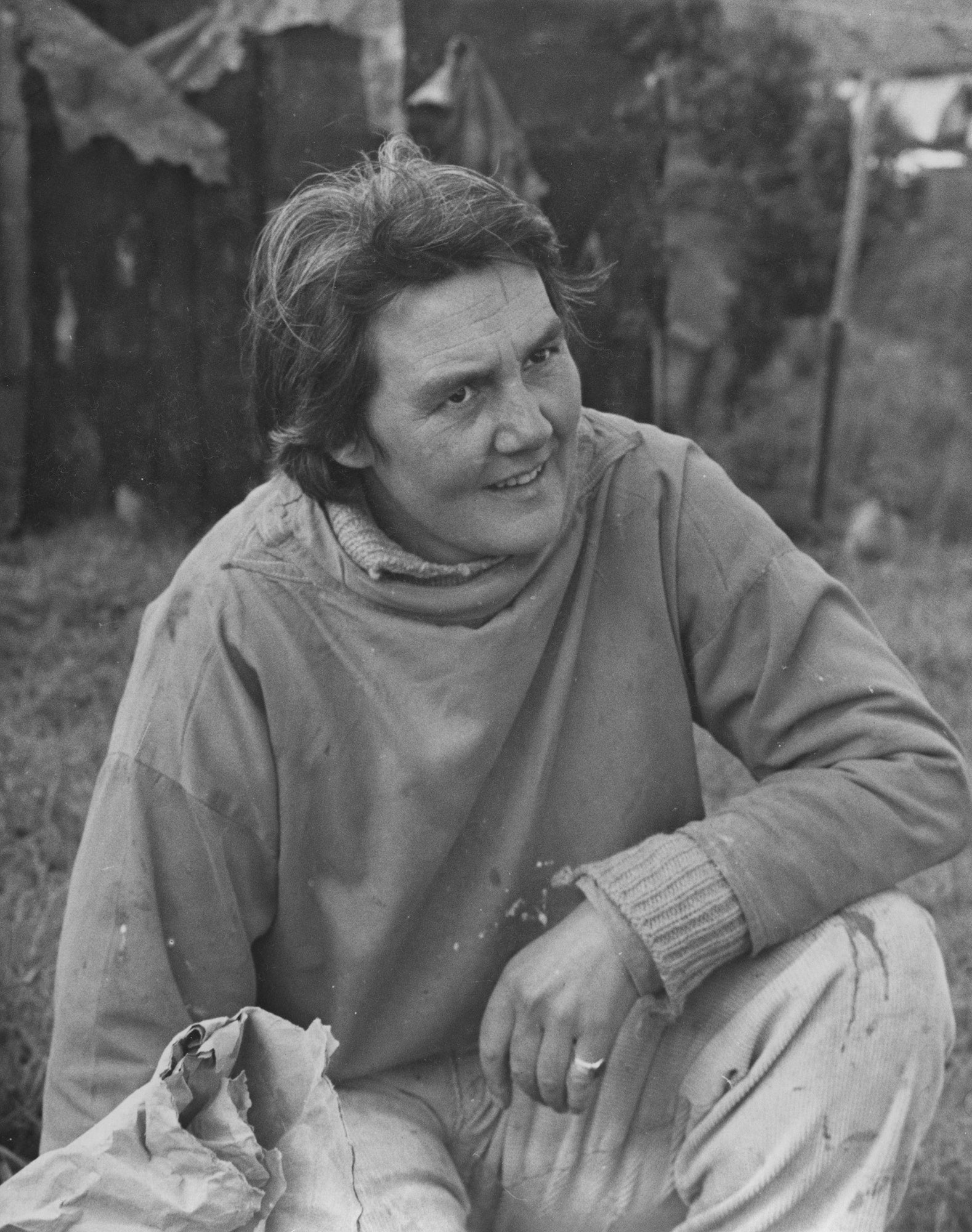

In Catterline, I met a man called Ron Stephen who grew up there, and knew Eardley when he was a child. He told me how his father drove him to Stonehaven, a few miles away, to collect “a young lassie” from the train station. “There’s no lassie here,” said his father when they got there. Then they spotted an androgynous figure in a tweed jacket and corduroy trousers. It was Joan.

Joan painted outdoors, whatever the weather, and Ron often used to stand and watch her. “She always had a wee bag of sweeties on her easel,” he recalled, but these sweets weren’t an enticement to stick around. She used to hand them out to kids – like him – to make them go away.

Even today, Catterline feels remote and spartan. When the sun shines it’s glorious, but when the sky darkens and the wind picks up it can seem very isolated indeed. Living there in the 1950s was a lot tougher than living there today. When Joan arrived, there was no mains electricity or waterworks. You collected your water from a spring – you had to boil it before you drank it. In winter, people lived by candlelight and gathered driftwood for the fire. In summer they arose at dawn and went to bed at dusk.

In 1954, Joan moved into another house in the village, but this was just as basic – a bare earth floor, an outdoor privy (no plumbing) and water from a communal pump. There was no electricity and no telephone. The rent was £1 a year. Joan adored this “great wee house” and the life that went with it, but she wasn’t just a posh girl slumming it. She worked hard and lived simply. She was happy to muck in, but mostly she kept her head down. The villagers admired her work ethic. They liked her and accepted her. She became one of them.

This acceptance was all the more remarkable because it wasn’t just Joan’s art that set her apart. She was also a lesbian in an era when such things were strictly taboo. Homosexuality was a criminal offence, punishable by imprisonment, and although lesbianism wasn’t illegal it was unmentionable in polite society. Yet Joan never had any trouble. These villagers didn’t have time for petty prejudice. Life was tough enough already and they were too busy getting by.

Joan had a series of relationships with women – some physical, some platonic. It seems prurient (and rather spurious) to try and work out which was which. Judging from her letters, her platonic relationships were just as intimate. Quietly, discreetly, she lived her life the way she wanted to. “Being a lesbian in itself isn’t a thing to worry me,” she confided to a friend, “but the trouble is that life hasn’t worked out well at all.” She eventually found fulfilment, but there was no way she could live openly as a lesbian, not in the way you can do today. Her family and close friends knew about it, but although some other people may have guessed, it never became public – not until a long time after she died.

Is her sexuality important? Yes, to some extent. It didn’t affect her work directly, but it was central to her identity. To call her a lesbian artist would be crude, but not to mention it would be remiss. “I think it was a very important part of her life – it’s what she felt, who she was,” says her niece, Anne Morrison-Hudson, who knew Joan as a child. “It wasn’t talked about because you just didn’t talk about that sort of thing.”

Yet the work is what matters most of all and the work she did in Catterline was astonishing – some of the finest landscapes and seascapes ever painted in the British Isles. “Whilst Eardley is often compared with JMW Turner, she has a more profound connection with John Constable,” observes Patrick Elliott, in his new book, Joan Eardley & Catterline. Yet although she bears comparison with both these artists, her palette is quite different – not the soft and subtle hues of southern England but the starker colours you find further north.

Her muscular paintings inhabit an extraordinary middle ground midway between figuration and abstraction. There is a raw intensity about her work which is rare in British art, more reminiscent of German Expressionists like Emil Nolde – a bold urgency about the brushwork, fierce and fiery, a dramatic use of light and shade. “Catterline has such terrific clarity and terrific light,” she said. “It’s a great place for skies here – clouds grow out of the sea, and almost as much out of the land, and seem to go on forever.” The fields behind her house and the sea below gave her the perfect arena for her painting. Everything she painted was within a few hundred yards of her front door. “It’s like an auditorium,” says Patrick Elliott. “The cottages hug the edge of the bay.” This bay forms a perfect semi-circle, like an outdoor theatre. No wonder Eardley liked it best in stormy weather, when the sea became a stage.

If Eardley had only painted Catterline, she’d still be remembered as a great artist, but this was only one side of her work. She divided her time between Catterline and Glasgow, and the paintings she did in Glasgow were just as good. Rather than staying with her family, in their comfortable house in Bearsden, Eardley rented a rundown studio in Townhead, one of Glasgow’s poorest districts. “I like the friendliness of the backstreets,” she explained. “Life is at its most uninhibited there.” The scenes she painted in these slum tenements were positively Dickensian, but though she never shied away from depicting the poverty and squalor of the place, nor did she indulge in mawkish pity. She portrayed Townhead just as it was – no better, no worse – and treated its inhabitants with proper dignity. “She has forged her own hard language,” reported the Glasgow Herald. “Within it can be found tenderness and delicacy as well as sheer strength and power.”

The big difference between her work in Catterline and Townhead is that while her Catterline landscapes were uninhabited, her Townhead cityscapes were full of life. She depicted the architecture, but she focused mainly on people – especially children, and one group of children in particular – 12 siblings called the Samsons, who lived with their parents in a two-bedroom tenement: all the boys in one bedroom; all the girls in the other. Living in such cramped conditions, they spent a lot of time out and about, and they were happy to pose for Eardley in her attic studio. She’d give them a cheese and syrup sandwich and a mug of tea. She’d give them a few pennies for the sweetshop, for Caramel Toffees and Irn Bru. She bought their parents clothes and coal. What makes these portraits so dynamic is their ruthless candour. Unlike most portraits of children, there’s nothing coy or cuddly about them. Eardley knows these children – she understands them. She cares about them, yet she pulls no punches. The deprivation implicit in these pictures is shocking, but their honesty gives them a heroic quality. Eardley paints the truth. These are pictures of children as they really are.

It’s a strange experience to meet the Samsons nowadays, as I did a few years ago, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, and see them in their sixties and seventies, standing alongside these paintings of them as children, preserved forever on a gallery wall. What’s even stranger is that the backdrop to these portraits has completely disappeared. Within a decade the grim tenements of Townhead had been demolished, to make way for a sociologist’s paradise of high-rise tower blocks. The sanitation was better, but the community Eardley had painted was destroyed.

Eardley didn’t live to see the destruction of Townhead. She died of breast cancer in 1963, aged just 42. “If you want experience and understanding of beauty then envy me now – but if you want happiness then don’t envy me because these things don’t bring happiness,” she wrote years before. She was talking about her art, and the depression that haunted her (“She found life a big struggle, I think,” says Morrison-Hudson) but it also said some-thing about the austere life she chose, in Catterline and Townhead. “Eardley was instinctively drawn to poor communities who lived on the margins, to people whose way of life was under threat,” writes Patrick Elliott. As she said herself, “You really have to be tough for this game.”

By the time she died, she was already a successful artist with a substantial body of work behind her, but it’s maddening to think what else she might have done if she’d had another 20 or 30 years. Even a few more years would have enabled her to build an international reputation. A lot of artists are only just getting started in their early Forties. We can only guess at all the paintings within her which were left undone. People in Townhead and Catterline used to ask her why she was always up so early. She told them it was because she felt there was never enough time. The other women in her family all lived into their nineties. Her sister outlived her by 50 years.

Eardley’s untimely death explains why she isn’t widely known abroad, but it still doesn’t entirely explain why she’s so little known in England. “I think there’s probably a greater tendency to look over the Atlantic and south to the Continent,” says Patrick Elliott. Yet when they’re actually given a chance to see it, English audiences lap up her work. In the last year of her life, Eardley had a solo show in a smart commercial gallery in London’s Bond Street. It got rave reviews in the Guardian, the Telegraph and the Times. All the paintings sold.

Eardley was too ill to attend the Bond Street show. She died a few months later, in August 1963, leaving £20,000 – a small fortune in those days – all of it from her paintings. Not that money ever meant much to her. It was all about the art. In a heartfelt tribute her close friend Audrey Walker, who probably knew her best of all, said she was two people – a quiet, shy individual, and a wild, courageous, compulsive artist. “I always identify Joan with the sea,” said Audrey. Joan’s ashes were scattered on the beach at Catterline. Sixty years since she died, the village still looks much the same. You can recognise all the places she painted. The only difference is now the fishermen are all gone. When I went there, I saw a seal bobbing in the bay.

Read More:

A few months after Eardley’s death, there was a major retrospective of her artworks at Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow. “For many of us, this memorial exhibition of Joan Eardley’s work is surely one of the saddest yet most significant experiences of our lives,” reflected her old tutor from Glasgow School of Art, Hugh Adam Crawford. He’d always told his pupils to follow their artistic conscience, even if the whole world was against them. Joan had taken him at his word and repaid the wisdom of his instruction. The show ran for three weeks. Thirty thousand people came. “We were there at the opening,” says Anne Morrison-Hudson. “It was a sad and difficult time.” Yet Eardley’s art has outlived her, and this year’s centenary celebrations will further enhance her reputation in her adopted Scotland. Here’s hoping it also helps to spread the word south of Hadrian’s Wall.

‘Joan Eardley & Catterline’ is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (nationalgalleries.org) from 16 May. Admission free, advance booking required. For more information about Joan Eardley centenary events throughout Scotland, visit joaneardley.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments