Do we really need humanoid robots after all?

Industrial robots have virtually eliminated the human workforce from the car assembly line, but could they realistically replace all human jobs? It’s unlikely, thinks Steven Cutts

For many years, Japan has led the world in attempts to build a robot which looks and acts like a human being. Something with arms and legs and a reasonably convincing face and mouth. As long ago as the 1970s, they began showing off their designs at a global tech meetings and managed to spread confusion among the European and North American delegates alike. While the concept of an android servant was both recognisable and attractive, it was still the stuff of science fiction. Basically, we were miles away from being able to build one.

Then, during the 1980s, it was widely rumoured that Japan would soon replace America as the world’s largest economy. Japanese engineers were doing so well that it was hard to see the future in any other terms. This is an event that never happened. Reports of a future in which Japan became the world’s number one economy were greatly exaggerated. Not only do they now suffer from a rapidly ageing population but they have fallen behind in the race to increase work efficiency.

A quarter of the Japanese population is over the age of 65 and there is now massive investment in devices that would help staff in a hospital or elderly care homes perform such basic tasks as transferring a patient to the shower and back again. For a human, this sort of work is fairly easy but for a machine, the manual dexterity required to move an invalid without causing harm is still impossible. In 2020, 47 per cent of all robots were manufactured in Japan so for this nation, more than any other, automating care is surely a straightforward task?

Apparently not. While the environment of a car assembly line lends itself well to industrial robots, the environment of a modern nursing home does not. The technical challenges associated with sorting cutlery or changing bed sheets wildly exceed the difficulties associated with industrial welding.

Meanwhile, having been economically humiliated by their former adversaries in the 1970s and 80s, the Americans did what Americans have always done: they incorporated new technology into the production process to increase their output per hour worked. In a society where population growth is relatively modest, prosperity can only be achieved by increasing productivity. Therefore, productivity was improved. To put this statement in perspective, the average GDP per person in California is almost double that of the United Kingdom.

Even in the service sector, Japan has a 40 per cent productivity gap with the United States and from a Japanese perspective, this gap might yet be addressed by the increased use of industrial robots. More than that, the realm of the robot might be extended beyond the shop floor and into the service sector or, perhaps even our everyday homes. For a country that produces nearly half of all the robots in the world – this is not an idle fantasy.

Most science fiction visions of a useful robot focus on a machine that resembles a human being. In essence it is a mechanical servant. When I was an undergraduate at Imperial College, I was persuaded to sit through a lunchtime lecture where someone tried to explain the technical challenges associated with trying to walk on two legs. It’s much harder than you ever imagined and I was pretty much convinced that we wouldn’t see two legged robots in our life times. I was wrong.

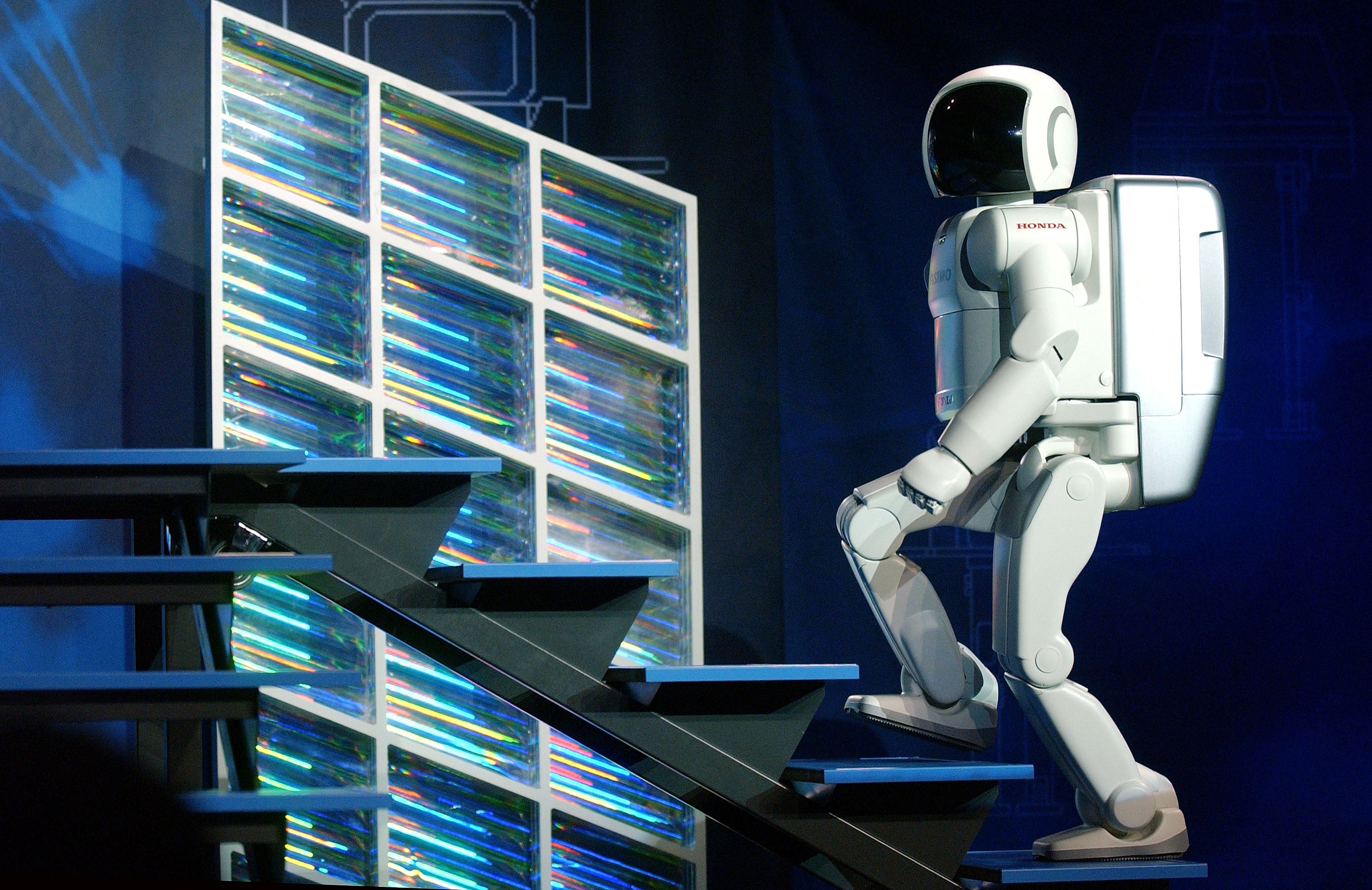

A number of design teams have now produced an entirely convincing two legged robot including the Japanese company, Honda. For some years now, Honda has flaunted its technology demonstrator “Asimo” at one tech conference after another and, in its final incarnation, Asimo could stand on one leg, run, climb stairs and pour a glass of water. All of these tasks represent basic level functions that would have to be performed in the hospitality industry in a future where human-like robots attempted to support human beings.

Background advances in software might also help with such a future. Advances in face recognition technology means that soon – very soon – a human-like robot would be able to look you in the face and tell you your name before you had chance to speak. They could probably infer your first language, occupation and home address in much the same instant.

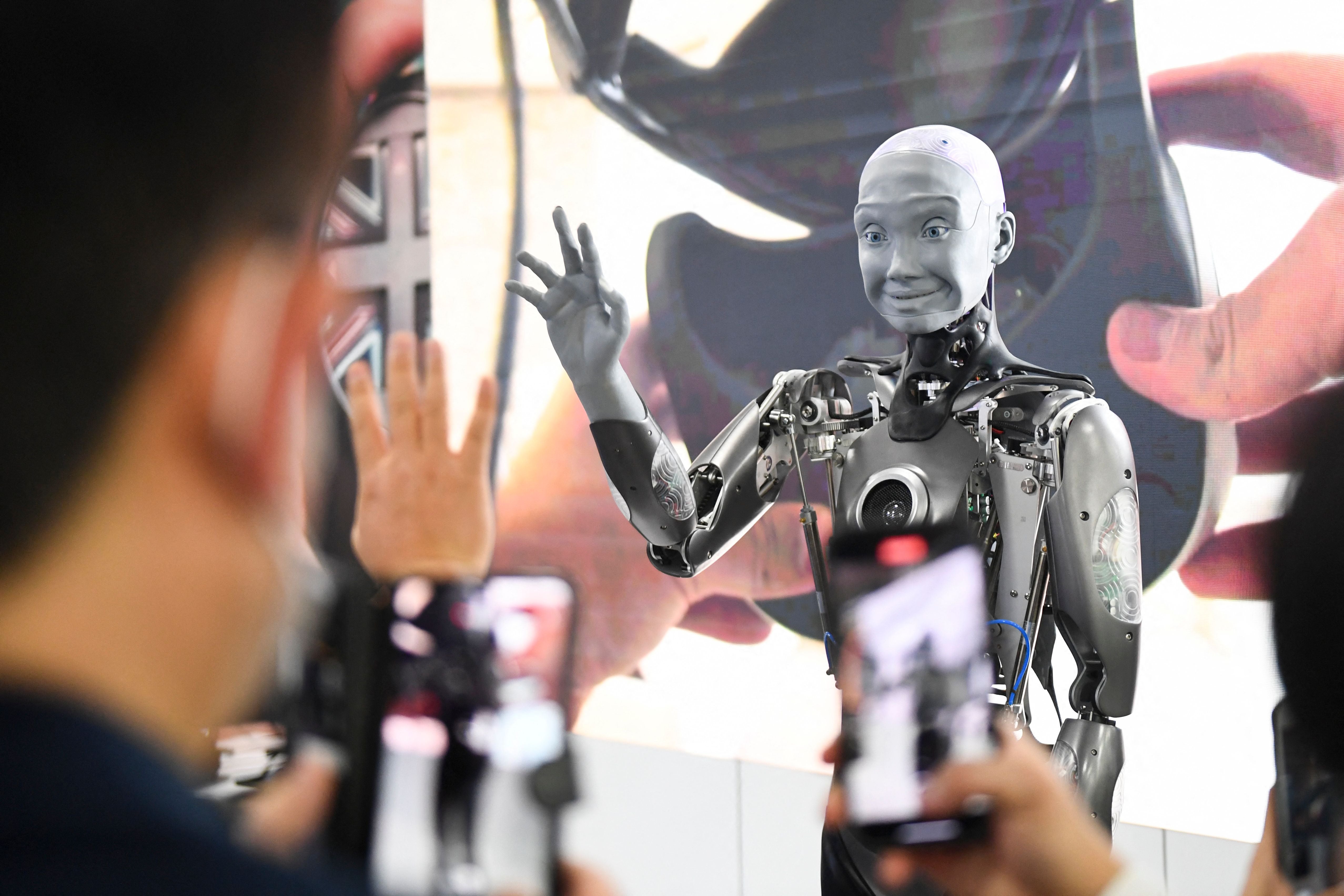

The machine reacts if a person intrudes into its personal space, leaning backwards and trying to waft his intruder away. It’s uncanny and it’s forcing us to consider a near-future reality

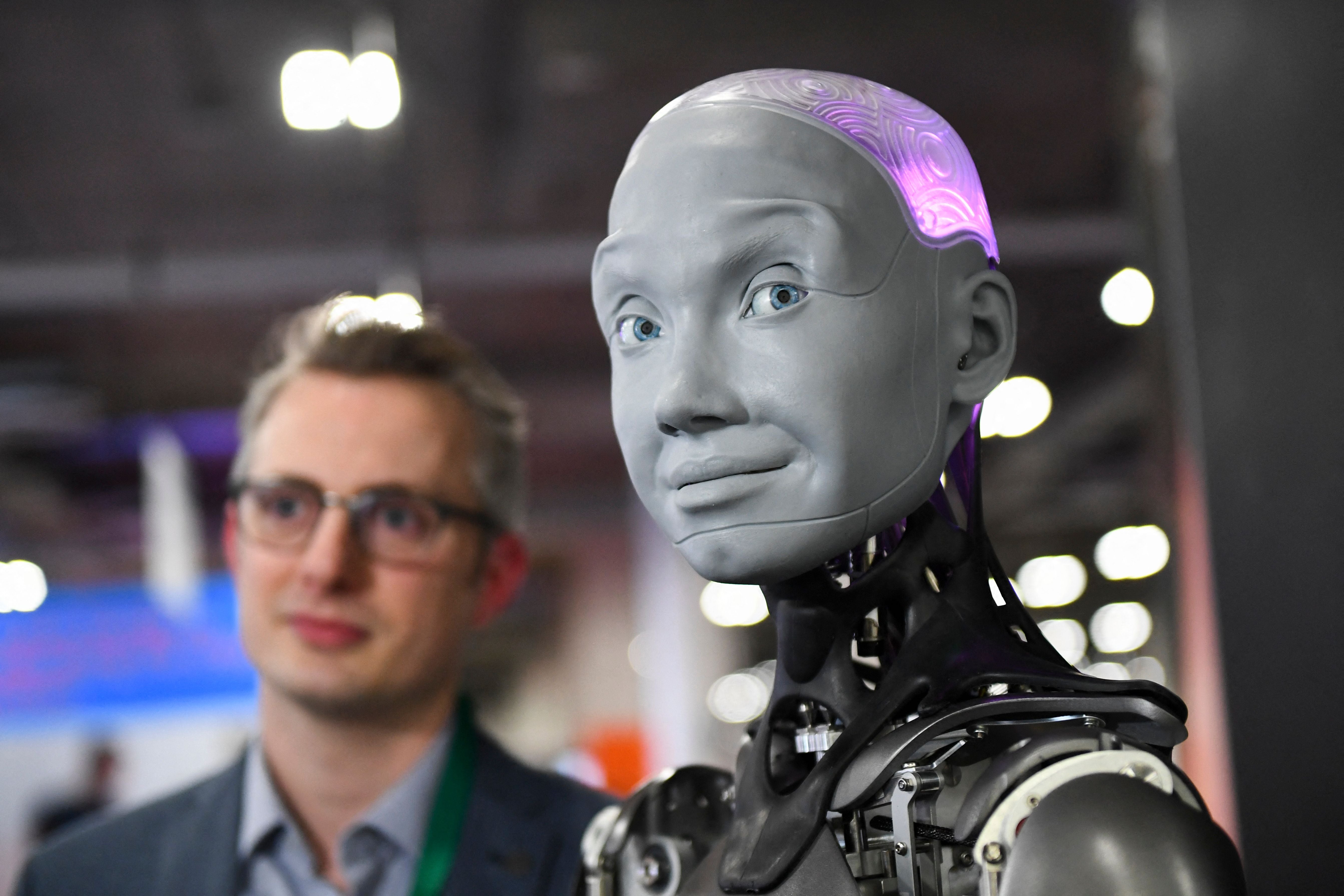

Honda has shut down the Asimo project and, right now, the machine everyone is talking about is “Ameca” a visually impressive humanoid robot with limited function and which bears more than a passing resemblance to the synthetic character in the Will Smith movie I, Robot. A British company by the name of Engineered Arts is building about three a month and they sell for between £200,000 and £500,000.

Engineered Arts is based in Cornwall and led by Will Jackson, who founded the company in 2005. “Robotics is a slow burn thing,” he says. “Boston Dynamics took 30 years to come up with a commercially viable product.” The voice we hear on Ameca is derived from an open source AI/chatbox system called GPT3, which uses deep learning to produce human-like text. On display in the entertainments industry, it can also be controlled by a human being and in the right circumstances it can pass for human, albeit for a very short period of time.

Like many British tech people, Jackson complains about the difficulty he has found in obtaining financial support. “All the people who ever gave us any investment came from overseas. Mostly North America.” Jackson is frank about the difficulties still faced by the industry. “The human hand is compressible. If you take hold of a glass, the contact area is enormous and the skin conforms to the shape of the glass. Now try to pick up two spoons and hold the glass using those. It’s harder. The contact area is tiny. In short, humanoid robots are a long way from being mainstream.”

These robots brought out as tech demos look better on YouTube than they do in life and the extent to which any of this tech is going to turn up in a nursing home anytime soon is limited.

Ameca is a technology demonstrator, an augment to the entertainment industry and – almost uniquely – a stand out success for the British robotics industry. As things stand many aspects of robotics and artificial intelligence are misleading. There are a few manoeuvres that a human like robot can do to create an exaggerated impression of realism. They’re distracting, but they’re misleading too. No current day computer-like brain has any insight of any kind into what a person is really saying to them although some of them are able to give you the impression that they have, albeit for a relatively short period of time.

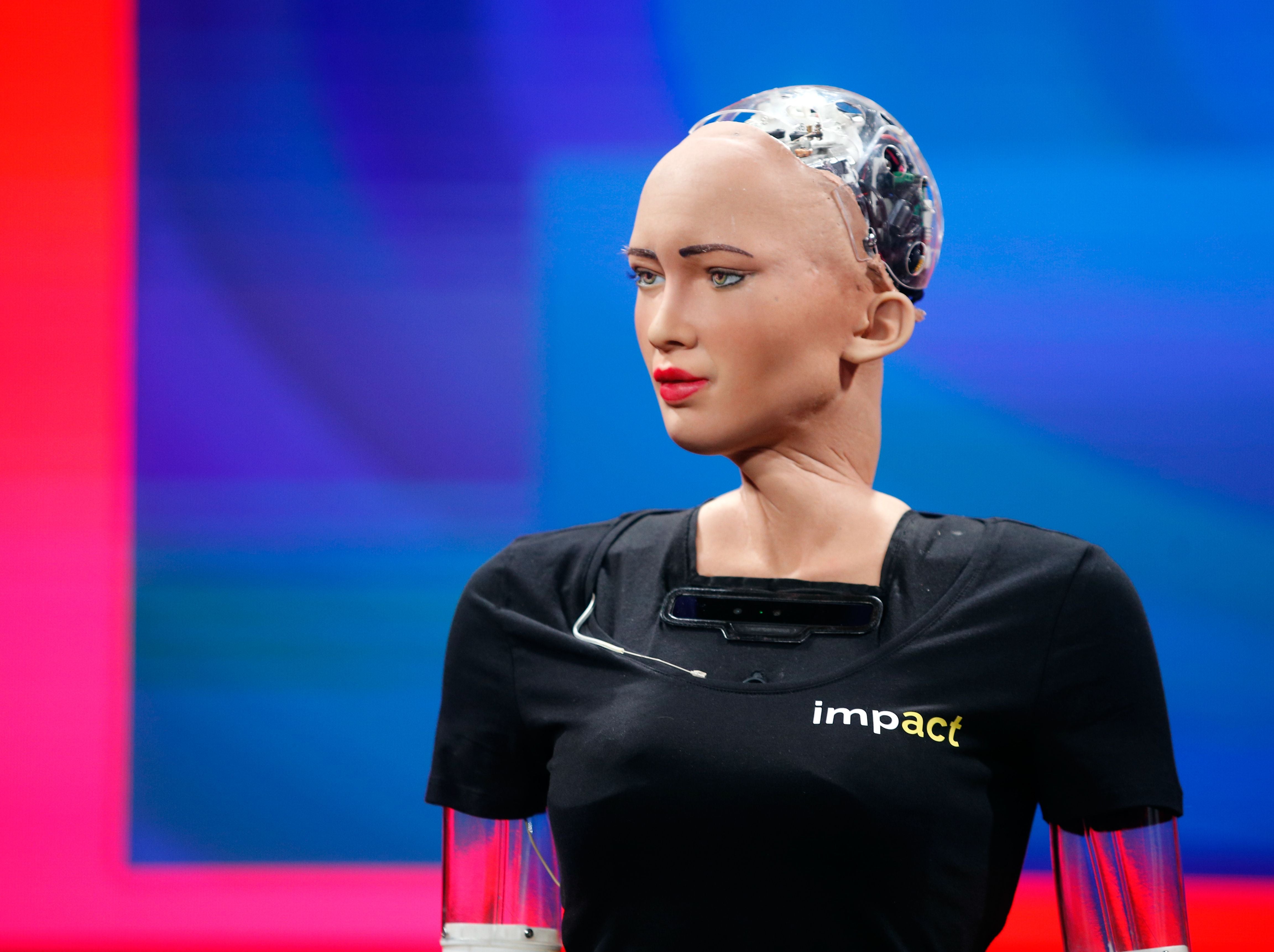

Hanson Robotics in Hong Kong has produced what appears to be a front-runner product in this field. It is the female, hair-free android-like creature, Sophia. Sophia has a similar image and presence in the current tech scene. Sophia’s main skill is the relative realism of the face and its apparent ability to respond to verbal questions and instructions. Just as Honda’s Asimo attempted to focus on walking on two legs, Sophia attempts to project a human-like presence to a living audience. (It should be added that like Ameca, Sophia also uses GPT3.)

In comparison to what is still to come in the future, all of these machines are primitive and in some respects, they have merely riveted together technologies that were already established. Speech recognition software is still improving but it has been commonplace for many years. A deeper cognitive understanding about what has been said or even more importantly what has been implied by a real human being remains wildly outside the intellect of even the best computers. In spite of this, a number of groups are still attempting to develop humanoid robots of the kind that have become familiar to us from the world of science fiction.

It doesn’t matter which jobs you manage to eliminate with machines. Once they have been eliminated, the indignant workforce can simply be shunted into another avenue of work

For its part, Ameca has learnt how to simulate some basic human-like movements and facial expressions. The machine reacts if a person intrudes into its personal space, leaning backwards and trying to waft its intruder away. It’s uncanny and it forces us to consider a near-future reality in which robots and humans interact on a regular basis and in a manner that we have not yet entertained. If they follow us into a toilet, will we care if they stand there and watch while we use the facilities? If we argue with a loved one, will it bother us that they are still in the room?

Given that these are machines without any real insight of any kind into the events that are occurring around them, we probably shouldn’t care but there are already individuals who are looking at how humans and robots will interact in what may well be a very near-term future. In the language of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, will these be the Epsilon Semi Morons of the social fabric? Freeing us from any sense of guilt about their professional position, since they are only a machine and needn’t show up on the Richter Scale for self effacement.

Jackson, in particular, is sceptical of the speed at which humanoid robots will appear on our streets. “When you design a two-legged robot you’re up against 7.5 billion human beings, all of whom are still light years ahead of the best robots.”

In some respects, it doesn’t matter which human roles you are able to replace with machines or indeed what the machine looks like. Virtual assistants or chat boxes may be more efficient in this purpose.

Think about it. You go to a bank – it’s closed. Banks are old hat. There was a time when they had a physical presence on the high street. There used to be a row of people behind glass screens, separated from their clients by security measures that already seem antique. That’s all gone now, most physical banks have been eliminated and nowadays they encourage their customers to use the ATM machine.

But what if we didn’t have an ATM machine? What if we encountered a synthetic person behind a glass screen and that same synthetic person attempted to hold a conversation with their client and responded like a human being? Would this work any better than a modern ATM machine? Probably not. There’s something quite attractive about the anonymity that comes with liquid crystal. With an ATM machine, nobody around you has any insight into what you are doing.

How then should we view the obsession with human-like robots? Japanese scientists have designed a machine that can roll a patient out of a bed that partly resembles a teddy bear. It doesn’t look like a health care assistant but it replaces one part of their job.

On the other hand, there may yet be some roles that just about anyone would gladly hand over to a machine. In the aftermath of the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant, the Japanese government realised that any attempt to inspect or repair the plant would expose human workers to high levels of radioactivity. Given that Japan is a world leader in robotics, it seemed reasonable to suggest that somebody somewhere would have a robot that was capable of climbing through the wreckage. Incredibly, no such machine existed.

Since then, enthusiastic further investment has provided machines that claim to be able to perform this task. At the same time, it should be remembered that the technical challenges of marching around a derelict nuclear reactor are as nothing in comparison to the challenge of working in an elderly care home. A robot is – for example – pretty much impervious to ionising radiation and the layout of a nuclear reactor is relatively static.

Industrial robots have virtually eliminated the human workforce from the car assembly line. They sit stationary and don’t attempt to move. There are no pension issues, no shift system and they do not participate in industrial disputes. The Japanese have 150,000 already and this number is expected to triple in the next 15 years. For the Japanese, in particular, robots have become a form of justification for an incredibly low level of immigration in a society with a low birth rate.

It doesn’t matter which jobs you manage to eliminate with machines. Once they have been eliminated, the indignant workforce can simply be shunted into another avenue of work that still requires the human touch.

People like Elon Musk had been predicting a self-driving car as the norm for Tesla a few years ago. He was wrong, we’re not there yet but there are prototypes on the road that can do exactly that and we’re skirting on the edge of a future in which hundreds of thousands of drivers might suddenly disappear from the workforce. Like many other changes in human history, the change might not come from the direction we expect but the disruption will still occur.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments