Years of scientific research between Russia and the west is lost in no man’s land

Russia has a talented scientific community, one that the west relies upon for many projects here on Earth and in space. So what happens now? Steven Cutts explains

Aside from the death and destruction seen on our television screens, the conflict in Ukraine has created havoc for scientists all around the planet. Men and women who have spent their entire careers trying to foster relations between Russia and the west are seeing their life’s work cancelled or delayed.

Although the Russian economy is smaller than that of Italy’s, it retains an impressive scientific community and has long punched above its weight on the international stage. In the aftermath of the recent invasion, most if not all of these projects are now on hold. For a project like the International Space Station (ISS), Russian participation is so intimate that a formal separation is almost inconceivable.

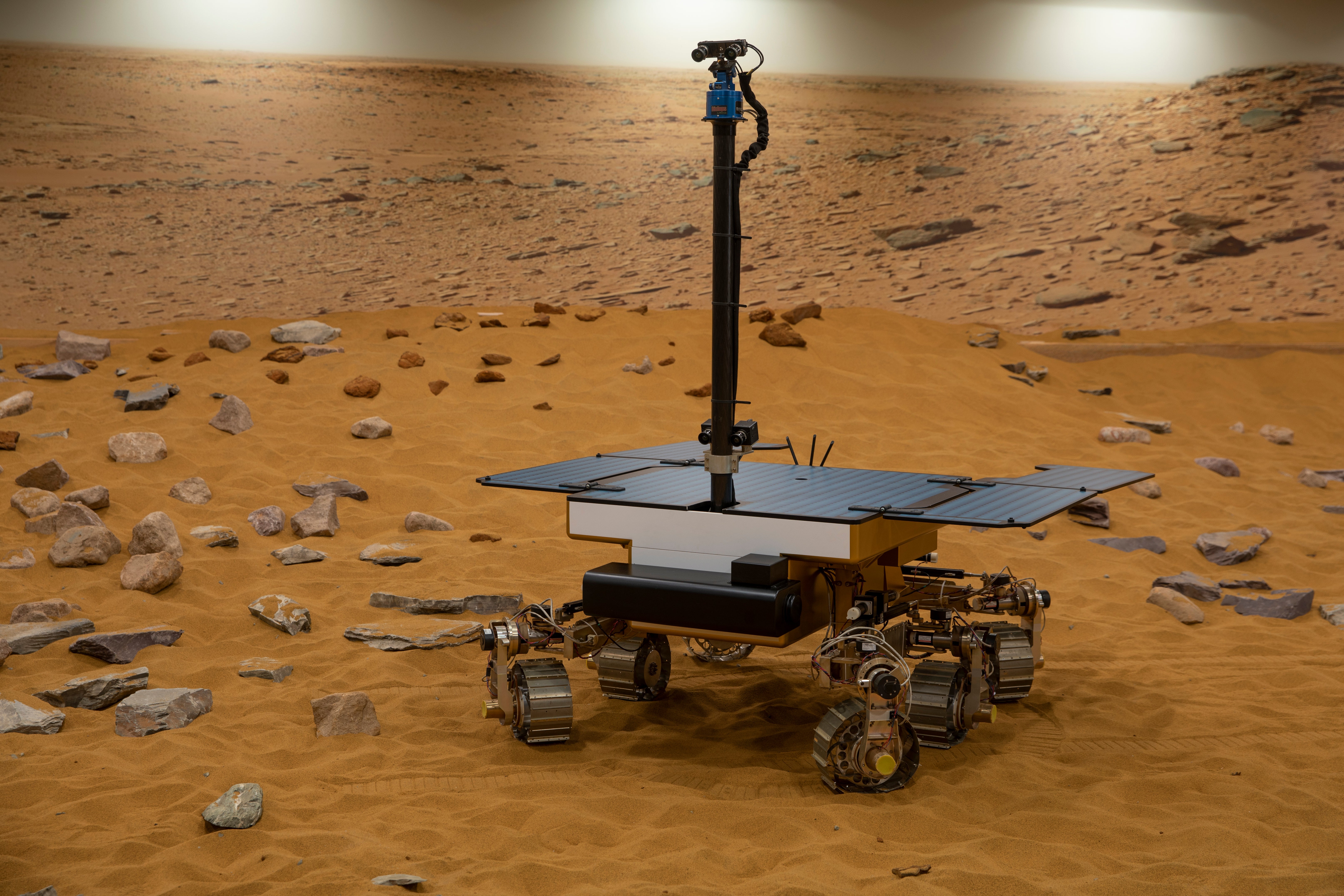

The impact on unmanned spaceflight is even worse. The Rosalind Franklin robotic probe is a joint attempt to send a European built rover to the Red Planet. Ironically, it was due to be launched a couple of years ago but managed to miss its launch window. All things seemed set for a launch in September of this year with a landing about six months later.

Unfortunately, Mars is a moving target and our two planets are only in the right position to launch for about two weeks every 26 months. If we miss the launch window, we have to wait another 26 months for the next one to arrive. Right now, the Rover is sitting optimistically in Stevenage, England, ready for a September blast off. However, since the actual landing system has been developed in Russia, the September launch is almost certainly going to be cancelled. Either the rover will end up in a museum or the European Space Agency will end up asking the Americans to develop an alternative bit of engineering.

The relationship gets even more complex for other projects. In the 1980s, the Soviet Space programme developed a new kind of rocket engine that burned kerosene and liquid oxygen. At first sight, this wasn’t a particularly exotic technology, but when western engineers were finally given free access to Soviet Space facilities, it dawned on them that the Soviets had found a way to significantly increase the thrust produced by a kerosene burning engine.

State-of-the-art American rockets used liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen and most of the engineers in Nasa had accepted that. Somehow, the Russians had found a way to milk an extra bit of thrust out of liquid oxygen and kerosene using a dual combustion chamber. With the Cold War over and the Soviet space programme collapsing, the order was given to destroy the engines but it was never obeyed and a whole row of them were left sitting in a warehouse.

In time the United Launch Alliance (an American consortium which builds rockets) managed to buy a few of them in bulk and use them – in their own launch vehicles. Today, the Russian built RD-180 engine is used for the first stage of the iconic Atlas V rocket and the discontinuity of supply is going to be a major headache for the Americans.

As a former member of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was given a major role in the construction of intercontinental ballistic missiles. With the Cold War over its Yuzhmash factory builds the first stage for the Antares rocket. Antares is used by the US-based company Northrop Grumman to resupply the ISS with unmanned cargo vehicles. It also represents a regular source of income and export for Ukraine. Since the factory is now occupied by Russian forces, it’s hard to know if this relationship will ever be restored.

Back on earth, the situation is just as bad. ITER, a futuristic project to develop nuclear fusion, is half-finished in France. The core reactor is basically a form of “Tokamak” – the word Tokamak being a Russian language acronym for a doughnut-shaped reactor dating back to the Soviet era. Not only have the Russians given the project its name, they’ve also invested resources in the construction and forthcoming operation of the spectacular new device. How will this one continue? As things stand, ITER has seven stakeholders including China, India, in addition to the US, Europe, Korea and Japan. Needless to say, keeping this particular collection of investors together isn’t going to be easy.

UK research and innovation is reviewing research projects with all Russian contacts although one can’t help but hope that at least some of these links could be reactivated

The irony here is that ITER was conceived by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev during the closing stages of the Cold War. ITER and the ISS were seen by some as a kind of diplomatic sanctuary where the rival powers would never get into conflict. Now, the emergence of a new hot war has brought the entire collaboration into question.

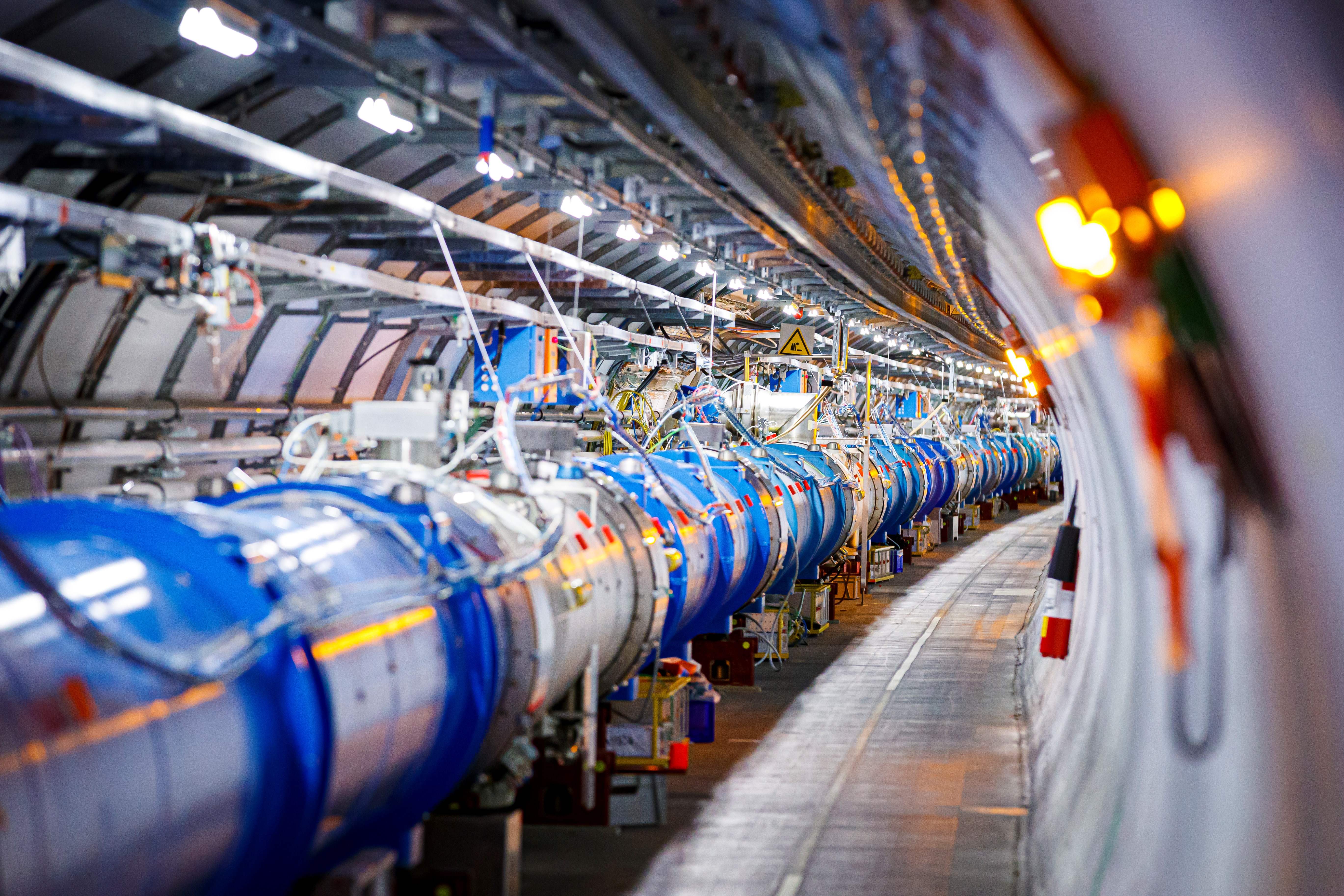

The European particle physics lab, CERN, has already suspended Russia from participation in its work. It’s probably worth noting that CERN did not expel Russian scientists when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968 or Afghanistan in 1979 and this may have been the sort of project where Putin just assumed that cooperation would continue.

The International Astronomical Union set up after the First World War to encourage cooperation in astronomy has yet to expel its Russian membership. Needless to say, the Ukrainian contingent is fuming. Pity the men and women who have spent their entire careers trying to foster friendship and cooperation between nations and who are now being asked to tear up everything they have worked for.

UK research and innovation is reviewing projects with all Russian contacts although one can’t help but hope that at least some of these links could be reactivated if and when some sort of settlement is achieved in Ukraine. A few days before the actual invasion, I asked a Russian financial analyst if Putin would really invade. No, she told me. It was all a bluff. But that didn’t matter. He had already won. Just by parking his tanks on the border with Ukraine, he had been able to increase the price of natural gas by 35 per cent. Putin’s entire economic strategy was based on the export of gas and oil. When those two prices plummet, his country goes into meltdown. When they go up, it starts to expand. She was wrong, Putin meant business and the attack on Ukraine has done a lot more than increase the price of oil.

In 2020, the British bought a major stake in the then bankrupt international satellite system “OneWeb”. OneWeb had planned to launch 600 small satellites into low earth orbit with the intention of providing broadband connection for people here on Earth. (About 400 of them are already up there.) The project was due to come to completion in 2022, but on 4 March the Russian space agency removed the Soyuz launch vehicle from the launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Unless something changes quite rapidly, it looks like OneWeb will have to find another launch vehicle in the next few months.

OneWeb might yet get there, albeit with the help of the British taxpayer, but for more ambitious projects, our own government may struggle to find the readies. The truth is that many major science projects are difficult for any one nation to fund. In effect, the British would have had to have thrown everything at fusion nuclear power while the French did the same for biotech and the Germans tried to come up with a new kind of very high energy particle accelerator. The chances of any one of these projects producing a commercially viable product are hard to determine and it’s not unreasonable to suggest that all of them will fail. But by interfacing the budgets and capabilities of several countries, it does become realistic for all of us to participate in a broad spectrum of high-risk projects that all of us would struggle to fund on our own.

Putin has campaigned for more scientific research in Russia, acknowledging the importance of such work to their own economic future

When the Cold War ended, the Russians – isolated by geography and by themselves – desperately needed to send their people to the west to understand how to translate their own talents into commercially viable products. Yes, the Russians have a lot of natural resources but their internal standard of living is far from impressive. Remember that the economy of Saudi Arabia is smaller than that of London. Even though we think of Saudi as a wealthy, resource-rich country, there’s only so far you can go by selling natural gas.

What’s sad about all this is that there was a time when the Russians never collaborated with the west on anything. There was a wall between East and West and if you tried to cross it without the right paperwork you could be shot. In the course of time, this situation came to an end and many people saw cooperation in science – especially “big science” – as a means of overcoming the divisions of the past. Think of the iconic imagery that stems from a Russian Soyuz capsule docking with the ISS. Suddenly, a group of Japanese, Russian and American scientists emerge into a hi-tech wonderland and the greetings that follow have become a symbol of international cooperation.

Less visible, although perhaps more important, were the attempts by universities to establish links with their former Soviet rivals. In the 21st century, many western academics were encouraged to get involved in new research at the University in Russia. The Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology was a new build English-language research University on the outskirts of Moscow. At first sight it sounds very promising, a definitive end to the global segregation that had been the basis of the Cold War. The Russians themselves were hoping to use it as a nucleus for their own version of Silicon Valley but for some years now there has been friction associated with the political position of the Russian government.

When a Russian-backed group shot down a Dutch airliner, one of the Dutch academics in stem cell research decided that he had enough. Obtaining an elite scientist like this isn’t easy and with an atypical behaviour pattern among your own government it becomes even more difficult to retain them. Amid the current wave of outrage about the situation in Ukraine, it’s hard not to feel sorry for the academics who have tried so hard to build professional links with global community, only to see their life’s work destroyed by a decision-making process that is so completely beyond their control.

The perversity of it only seems to increase when one looks at Putin’s performance on the domestic scene. Putin has campaigned for more scientific research in Russia, acknowledging the importance of such work for the country’s economic future. A couple of years ago Putin ceremonially opened a Mercedes-Benz factory in Russia, accompanied by the German economics minister. Now he’s demonstrated a willingness to turn his back on most or all of that for the gain he expects to obtain from one special military operation.

More recently, and in an absolutely bizarre development, three Russian cosmonauts flying to the ISS drifted into the zero-gravity interior wearing T-shirts in the colour of the Ukrainian flag. Had they smuggled the outfits aboard without the knowledge of higher authority? Were the ground crews complicit in this action? What sort of reception do they expect to receive when they return to Earth? Mission Control has dismissed the colour scheme as a coincidence.

Amid all this, it’s important to keep some kind of perspective. For many years the Berlin Wall seemed to be eternal, a permanent presence in the centre of a once great city and an absolute gift to thriller writers everywhere. From where we stand now, it was a very brief footnote in human history. Having been built in 1962, it was on its way down by 1989, a remarkably short period of time. Eventually, the fighting in Ukraine will end, but it will be many years before the international community feels relaxed enough to get involved in Russian science again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments