The world is grounded and the birds are making hay in the sky

The world’s airlines have been put to rest, at least for the time being. Deanne Stillman reflects on her relationship with flight and finds as much joy gazing up at the sky as she did looking down from it

When I saw the images of jets parked at the aircraft boneyard near Phoenix, I burst into tears. They had been flown there in the aftershock of news about the coronavirus outbreak, and now they were all lined up in the drylands, where so many of our dreams and vehicles are preserved forever. Seeing the planes in that regard was the first time I fully realised the plague was upon us. The nation that had invented flight, gone to the moon, broken the sound barrier, was now grounded. Our planes were mostly empty; there would be no reprised late-night jokes about who did or did not press the cabin crew call button, no singing flight attendants on Southwest Airlines to brighten our time on crowded flights; no pilots suggesting that we look out the windows on the left side of the plane if we wanted to see the Grand Canyon, or letting us know that we were coming in for an approach and we might encounter some headwinds, or that our estimated arrival time was in 10 minutes, right on schedule, maybe even a little ahead of it, and thanking us for flying on that airline. For the first time, our great American dream of escape was foreclosed.

But my sadness was tied up with something else. I had a strange riches-to-rags upbringing, and airports were a significant part of it. I was a little girl when my parents got divorced, and my mother, sister and I moved from a well-to-do part of town to a neighbourhood where people eked out a living at blue-collar jobs and were considered pariahs by those in our previous zip code. Suddenly, we couldn’t afford vacations – although we were fortunate to have relatives in New York who provided us with car trips and plane travel to the east coast during the summer or for special occasions. But we liked having our own getaways too, and it became a tradition for us to spend a long weekend every summer at the airport hotel. This was because we liked watching the planes take off, signifying the places we would go and the things we would do when we got there. We never said it like this, but the underlying theme was will we ever get out of Dodge? The reference is to Cleveland, Ohio, where my mother had become a “divorcee” (as in slut; as in Barbara Stanwyck movies), and I was heading for college to get an “MRS degree”.

As soon as it got warm enough, we would check into the Cleveland Hopkins Hotel – and go swimming. You see, it had a swimming pool, and we also liked to swim. My mother had been a lifeguard in high school, and was in fact quite an athlete. An equestrienne par excellence, she had gotten a job at Thistledown Racecourse after my parents split up, becoming one of the first women in the country to ride professionally as an “exercise boy”, the hardy souls who worked out thoroughbreds in the morning before their subsequent races. This job was a big deal at the time and she became something of a novelty, attracting the attention of the local paper – and the parents of some of my friends, whose perception that my mother was weird because of not having a husband was amplified by her choice of employment.

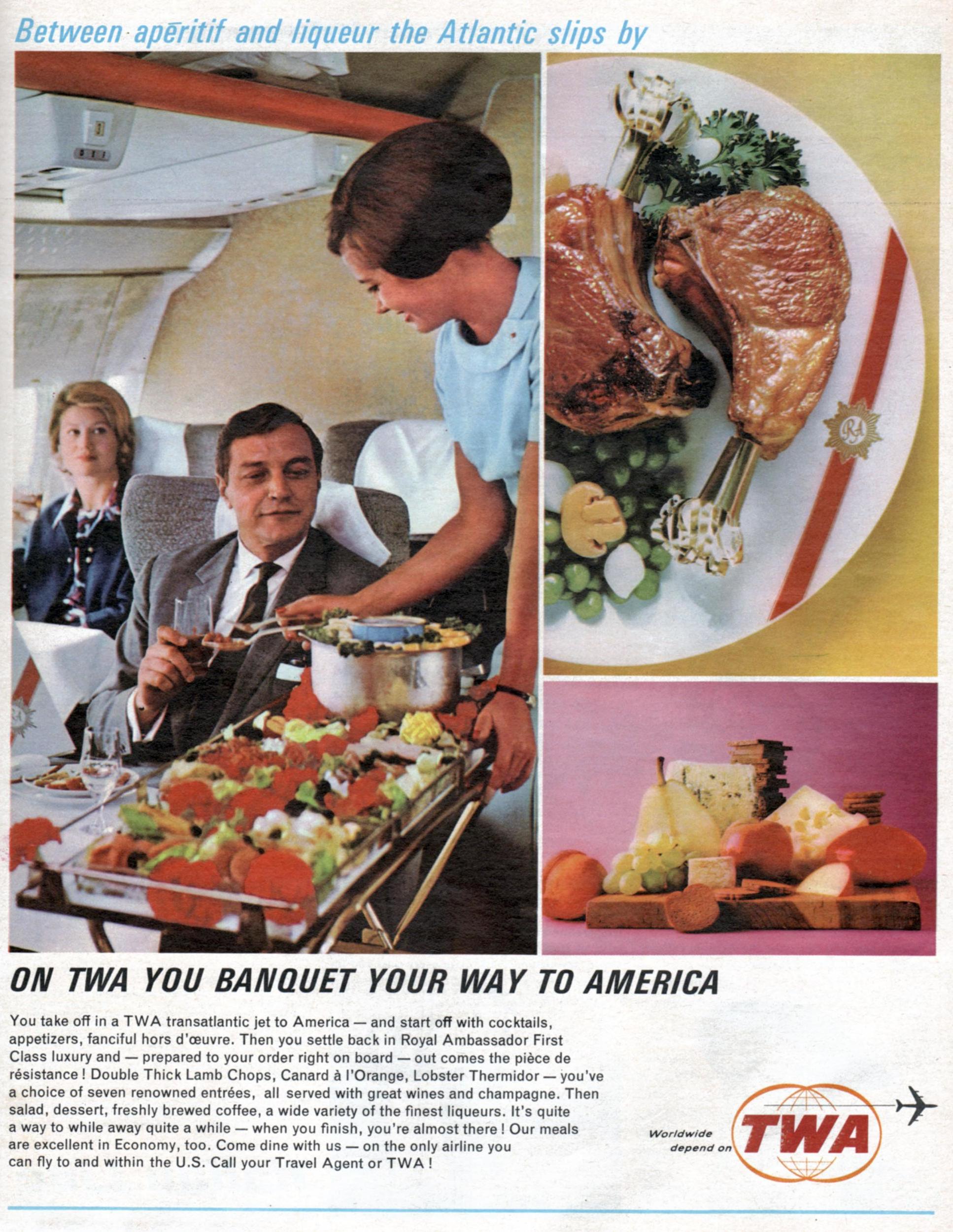

At the airport hotel, all of that fell away. It was easy to watch aeroplanes taking off then. There was no security; no mobs of people waiting to check in or coming off planes. There was simply the joy of possibility. I remember standing on the observation deck and watching jets coming in from… where? I would guess, according to the airline. There was TWA – probably from New York or beyond! There was United – from Denver, perhaps, or San Francisco or Seattle; there was a rhythm to the announcements which were flashing on a board and on the public address system, and there was a comfort in the departures too. The insignia on the wings were so close as the planes took off, and I was transfixed by all of them: there was the maple leaf on the Air Canada planes, suggesting forests and woods and trees forever; there was some sort of fierce bird that accompanied Eastern Airlines’ “fly the silver fleet” slogan and then there was the majestic eagle of American Airlines fame, both conjuring an ascent from the Earth to the heavens, suggesting what the planes were about to do any minute now.

These modern pictographs were accompanied by sound as well. Many of the planes I observed from the deck were not jets but had propellers, and watching and listening to each of the engines rev and the propellers turn and then turn faster until the plane was ready for take off was somehow enchanting. I guess the sound was part of the wonder and it signalled promise and a new life somewhere out there beyond the skyscraping Terminal Tower of downtown Cleveland (it was a rapid transit hub, not literally the end of all things, though of course my friends and I made jokes about that at the time), and then from the deck I followed each plane as it headed north, above the rides at the Euclid Beach amusement park that I knew so well. There was Over the Falls, a boat that carried people up a hill on a motorised track and then made a steep descent, heading around curves, then up and down again, now with water streaming down on the sides of pretend hills and diving right into a pool of water as everyone inside the boat ducked for cover and then lined up again for more when the ride was over.

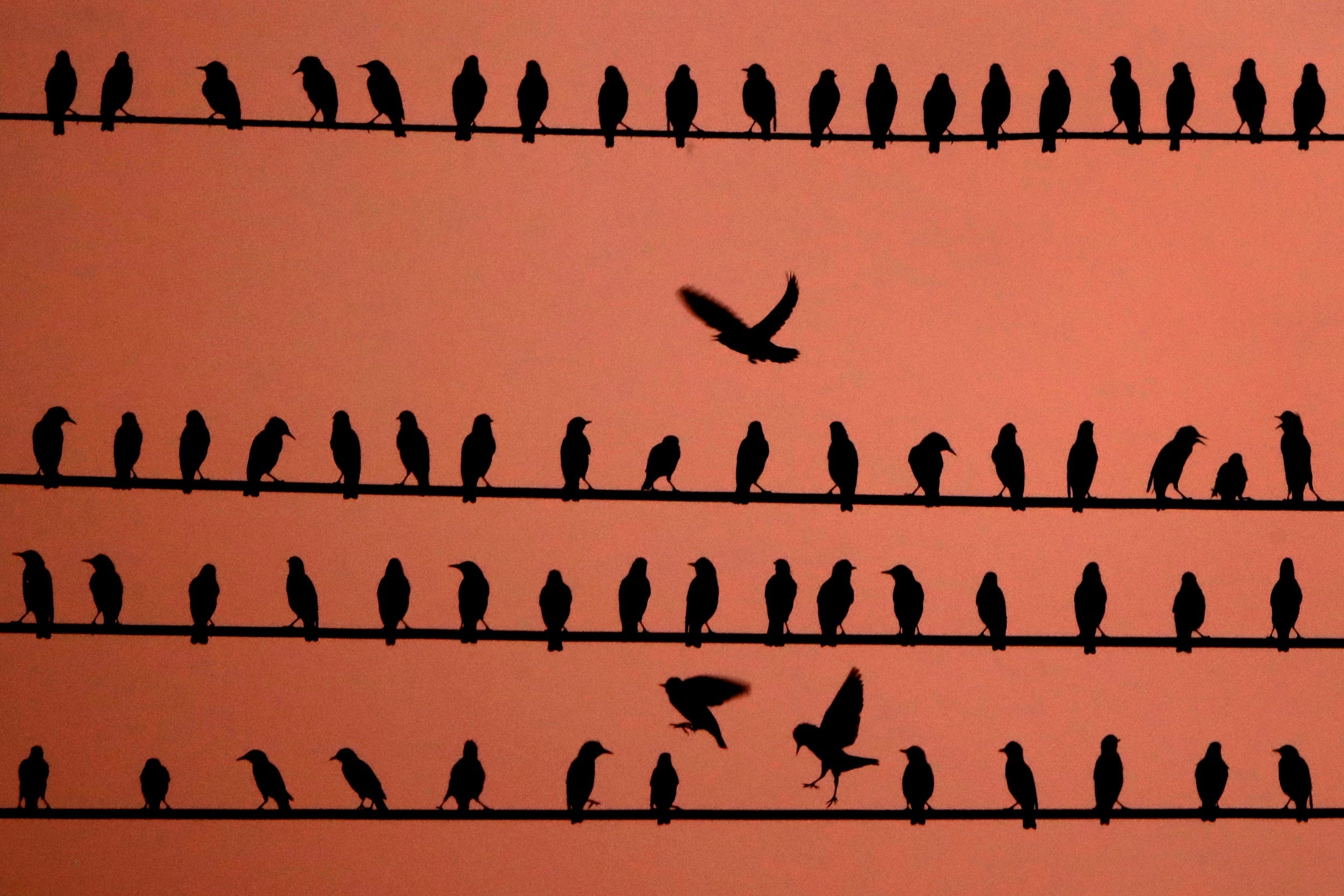

Nowadays, sitting in my yard in Los Angeles, I can’t think of a time when I have heard so much birdsong. Most cars are parked and there’s no traffic. The birds are singing all day long and I like it

There was another favourite, Rotor, the round room with rubber walls and the floor that dropped when the room started spinning but you would stick to the walls due to friction and laugh and scream, and come out of it feeling dizzy and elated. To those beloved thrills I bid farewell, staying with the flight path of each plane, heading ever northward – over Lake Erie and its endless chop, and then higher and higher, through a cloud bank, ever-present, and on to points across the land, and maybe some day I would be up there too, heading for a new place where I could start over, go home to a self that had been taken away.

At the end of an afternoon of sky-watching, we would head to the airport restaurant, the good one, and there we would order the best: steak – not just any steak, but filet mignon – and potatoes – not just any potatoes, but big, fat baked ones with fresh sour cream and chives. When our meals arrived, each steak had a little flag in it, saying how you had ordered it, and that too was a part of our yearly ritual that we awaited. I think it was the flags that made it so festive, like a holiday; “Look ma! Dinner has flags!” And then it was back to our suite and watching Ghoulardi (the local monster movie series so named after the host) or westerns or The Three Stooges (yes, we loved them, even my mom, and personally, I haven’t recovered from the replacement of Curly with Curly Joe or Moe for Shemp). The following day, we would watch the planes all over again, and I always planned a great escape to where it did not matter – though wide open space with cactus and red rock mesas were often part of the picture.

For my high school graduation present, I had requested a suitcase with my initials on it, and on that day, there it was – the travel-size blue Tourister I had dreamed of, emblazoned with “DS” on a badge. Soon after that, I flew away. I returned to the nest from time to time, but of course it was never the same. One day, my mother left too, flying away to Manhattan to join me, a place she had longed to live for many years. And later, my sister left too. We kind of all went our separate ways, coming together for special occasions and holidays and disasters, but for me at least, nothing could compare to those days at the airport hotel.

I like walking and hiking, and have hiked the trails of the desert west and southwest many times. I take great pleasure in communing with the flora and fauna, and the sights and sounds. If there’s a tortoise, I say hi, and if there’s a lizard, I say hey, and they return the greeting, though not all of the time. Sometimes Joshua trees dish out advice and baseball news; after all, the desert is the eternal ballpark, and if those trees can’t have the last word, what’s the point? One of the things I like listening to more than anything is birdsong. In the desert, you can count on the chittering of cactus wrens in the morning and the calls of other winged creatures throughout the day and into the night. Listen up, the ravens are talking! Did you hear that screech owl? Nowadays, sitting in my yard in Los Angeles, I can’t think of a time when I have heard so much birdsong. Most cars are parked and there’s no traffic. The birds are singing all day long and I like it. This is going on all over the country, and world, as many proclaim, delighted that we are returning to the land and the skies of the Before Time, not just before the virus, but before the embrace of ways that have severed us from the natural world.

Over the years the eagle has made a comeback, but now, if the rollback is approved, our American mascot may once again face darkness

Several years ago, I had a dream about a falcon. It swooped down low, right across my face, and I felt the air move and I could make out the design of its feathers as it slowed for a moment and then it ascended out of my sight line and sleep. I awoke startled and in wonderment. I had had other dreams of wild things in the past, but none that involved such close proximity. At the time, I had been weighing an important decision, involving a move from one city to another, a flight in every sense, and I received the visit from this raptor as a sign to swoop down and make the choice without hesitation, a departure and return of the heart. A few weeks ago, before the virus had fully made itself known in California, I dreamed of a falcon again. Whether it was the same one I do not know. It appeared this time at a slightly different angle, and the feeling of the dream was that an ally had returned. I wasn’t sure what to make of it in the days that followed, and I’m still not. But here’s what I know.

From birds we have learned to sing and to fly. We can all imagine our ancestors listening to their caws and whistles and deciding to copy them because it was pleasant and our own songs carried a message to others of our kind. Certainly, the human heart has long desired to soar, and when we were able, we copied the thing that winged creatures do. We studied their flight patterns, learned all about air circulation under and above their wings, came to understand the mechanics of feathers (and sometimes appreciate the beauty), and then, after we had designed our own versions of them, we joined them in the air for pleasure and for war, sometimes assigning our jets names such as “eagle” and “osprey” and “falcon”, and gathering to watch our very own sky warriors fly in formation during ceremonies and holidays and tributes.

There is now a move afoot to strip protections from birds. The Trump administration has proposed a rollback of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, one of the first environmental laws in the country. It protects over 1,000 species, and without it, for instance, Exxon would not have been held accountable for the “incidental take” – or loss of birds that occurred during an act of commerce – that was a result of the catastrophic Valdez oil spill in Alaska in 1989. At the moment, the administration is also acting under the mantra of “cutting red tape” by seeking modifications to the Endangered Species Act, the landmark legislation signed into law by Richard Nixon in 1973. “We need the tonic of wildness,” he said two years earlier when signing the bill protecting wild horses and burros, quoting Thoreau. It was a curious statement coming from a man whose downfall would come from his desire to control people, but even this paranoid president was stirred by creatures that galloped and took to the air in freedom. One of the first animals protected under the Endangered Species Act was the eagle, then at risk of extinction because of unchecked use of an insecticide. Over the years the eagle has made a comeback, but now, if the rollback is approved, our American mascot may once again face darkness.

It is said that during the Revolutionary War, on a morning of one of the first battles, a nest of sleeping eagles was woken by the noise. The eagles took flight and called out in response, shrieking for freedom and urging the soldiers on. The mighty and majestic raptor soon became the symbol of the struggle, and later, when the war was won, it became the national emblem, representing our greatest ideals, soaring high above land and sea, leaving the past behind and heading for a bright and unfettered future.

“If birds glide for long periods of time, then why can’t I?” said Orville Wright as he and his brother Wilbur toiled away on their invention of the first aeroplane. We can and we have, and now we have come in for a hard landing. As I listen to the birds in the trees around me, I try to understand what they are saying. I check out bird watching websites and visit archives where their songs are forever preserved. Did you know that their songs are a language, conveying messages regarding territory and what to watch out for and location of mates? Kind of like our own songs, I guess, but without crowds and amplifiers. I wish my mother were around to hear them, I think, for she too loved what was wild and free. On the other hand, I would not want her to experience this troublesome time of a modern plague and I’m sure it’s for the best that she passed away almost two years ago. And I hold ever closer those days at the airport hotel, when she made sure that I witnessed the path of escape, and gave me that suitcase so I could get out of Dodge.

Deanne Stillman is a widely published, critically acclaimed writer. Her books include Blood Brothers, Desert Reckoning and Mustang

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments