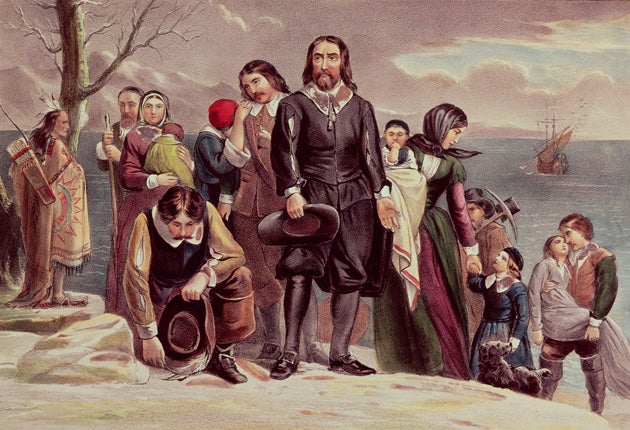

The American Dream? Not for all the pilgrims

Thousands returned within a few years of crossing the Atlantic, academic reveals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The American Dream was fading almost before it began, says a study which shows a quarter of all pilgrims gave up on the New World to return to Britain.

The harsh realities of life in 17th-century Massachusetts, where disease was rife, the climate unforgiving and the economy stagnant for long periods, forced thousands to make the treacherous three-month voyage back across the Atlantic within a few years of arriving.

Dr Susan Hardman Moore, of the University of Edinburgh's School of Divinity, has painstakingly researched the immigration records of ordinary people who fled religious persecution before the English Civil War, along with their wills, diaries and letters. Her book, Pilgrims: New World Settlers and the Call of Home, estimates that up to 20,000 people set sail across the Atlantic during the 1630s and 1640s as the country was torn apart by political and religious differences under Charles I.

Those who remained in America set about building a powerful national story which fuelled notions of Manifest Destiny and helped turn the country into the world's greatest superpower, but the vast numbers who quit have long been underplayed by historians. Among those to sail back to Britain were significant sections of the colony's elite, including a third of religious ministers and half of the graduates from the newly established Harvard University.

"This is a story that has been overlooked on the whole by Americans who prefer to focus attention on the onward march of United States' history," Dr Hardman Moore said. "My book, in a quiet way, undercuts some of the grand American mythology of a city on a hill that everyone is going to look up to as a beacon."

But it was not just conditions in their adopted home that fuelled the return exodus, Dr Harman Moore says. The execution of the fiercely anti-Puritan Archbishop Laud signalled a sea change in religious attitudes in the home country, and Oliver Cromwell's new regime offered new openings for adventurers, particularly those ideologically committed to the Puritan cause. Their presence helped reinforce garrisons of Cromwell's forces from Cornwall to Scotland at a time when English Presbyterians were less than keen to engage in the brutal business of suppression.

"Cromwell's new regime needed a huge number of people to run it so there were a lot of new opportunities in employment, at a time when in New England there aren't that many jobs because immigration and expansion has dried up," said Dr Hardman Moore. "England, Scotland and Ireland offered better opportunities."

Crossing the Atlantic was a major undertaking even for those who felt their actions were determined by God. Apart from the obvious dangers of shipwreck and prospect of long months of sea-sickness, many borrowed heavily to make the voyage, which cost the equivalent of a year's income for a craftsman.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments