Is anime finally breaking into the mainstream?

After three major exhibitions in London and the release of Studio Ghibli on Netflix, the beloved Japanese art form is finding a new audience. But there’s still a long way to go, writes James Moore

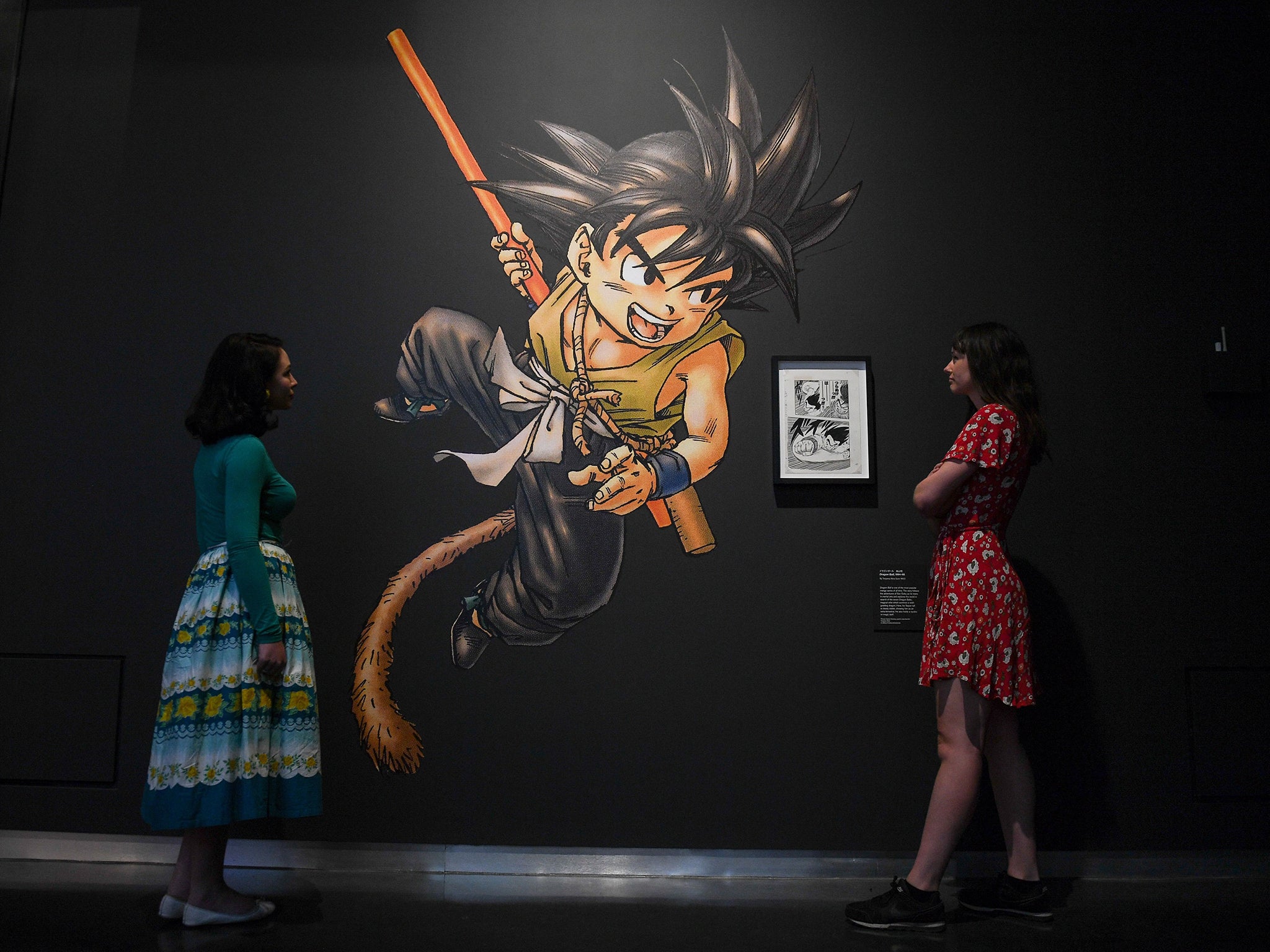

With his staff at home, cinemas shut and the progress of rights negotiations slowing to a crawl, anime evangelist Andrew Partridge faced the sort of challenge that would trouble even some of the medium’s fabled protagonists. The previous year was a banner one for Japanese pop culture. There were two major exhibitions in London devoted to manga (the source of some of anime’s biggest franchises), one at the British Museum, another at Japan House. The Barbican, meanwhile, devoted a season to classic anime movies.

The regular conventions, events such as Partridge’s own Scotland Loves Anime, continued to be wildly popular. Passionate fans could have been forgiven for thinking the long-anticipated breakthrough from cult to mainstream was in prospect, that they were in sight of the dawn of the Animeaissance. Netflix securing the rights to Studio Ghibli’s entire catalogue (with the notable exception of wartime weepie Grave of the Fireflies) only added to the sense of anticipation.

Then Covid-19 happened. From crisis, however, springs opportunity: Patridge’s company, Anime Ltd, has responded with the launch of Screen Anime, the medium’s first online film festival. He is very keen, however, to stress that this shouldn’t be seen as an attempt to capitalise on the pandemic.

“I asked my staff to come up with ideas, but the key point was they would have to work both during and after the pandemic, otherwise it’s just opportunism in the face of suffering. We think this can do that. It will provide fans and newcomers alike with an outlet at a time when cinema screens have gone dark. But it could serve a real purpose for the anime community afterwards.”

How? Patridge points out that audiences outside major cities often find it extremely difficult to see anime films when they appear, almost inevitably on limited release.

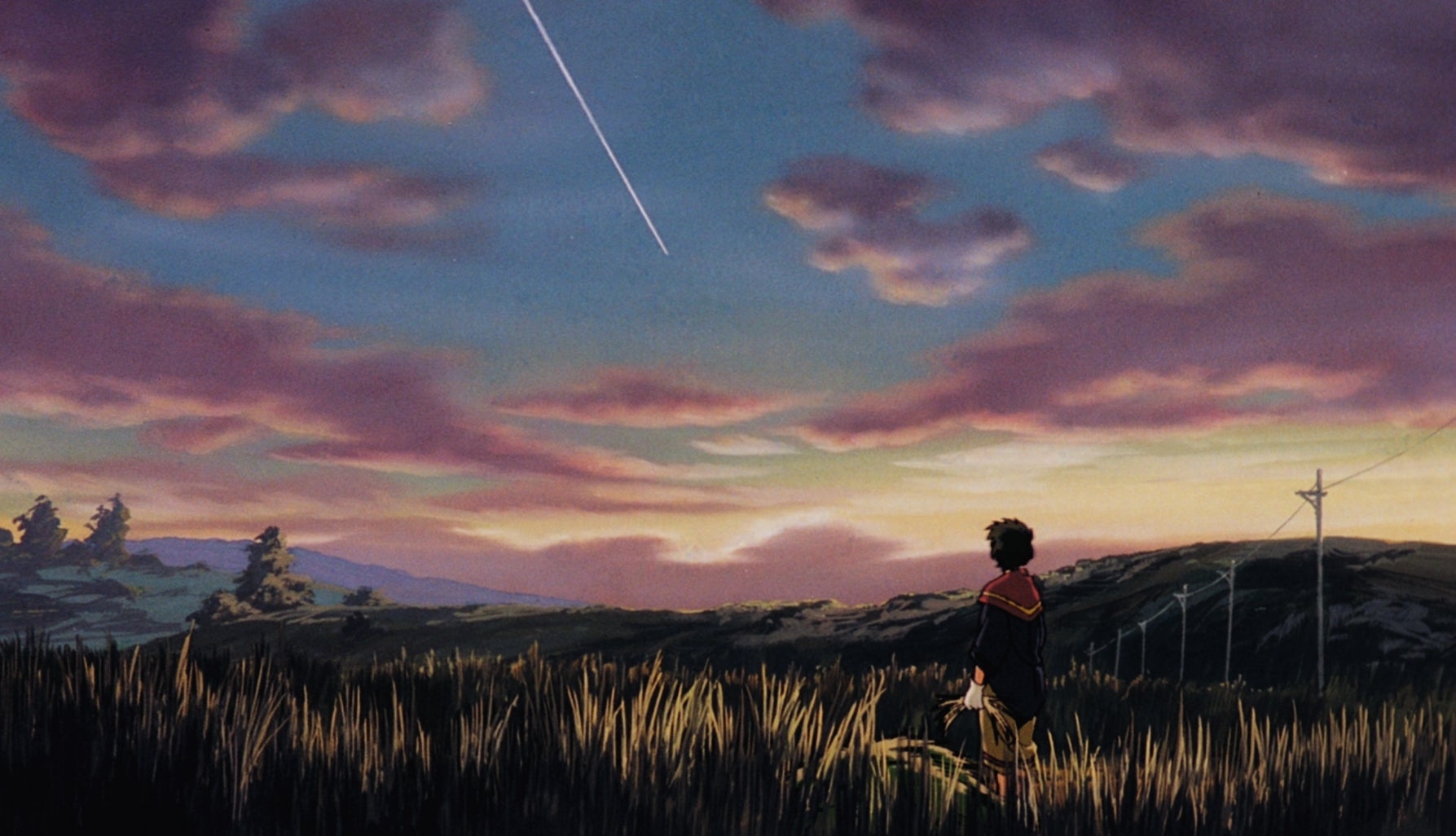

It’s changing. He had to beat off competition from major studios for the critically acclaimed Weathering With You. Their interest was piqued by the success of director Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name, a still relatively rare picture that can boast some name recognition outside anime’s committed fans.

Interested in anime adventure?

Here are five recommendations

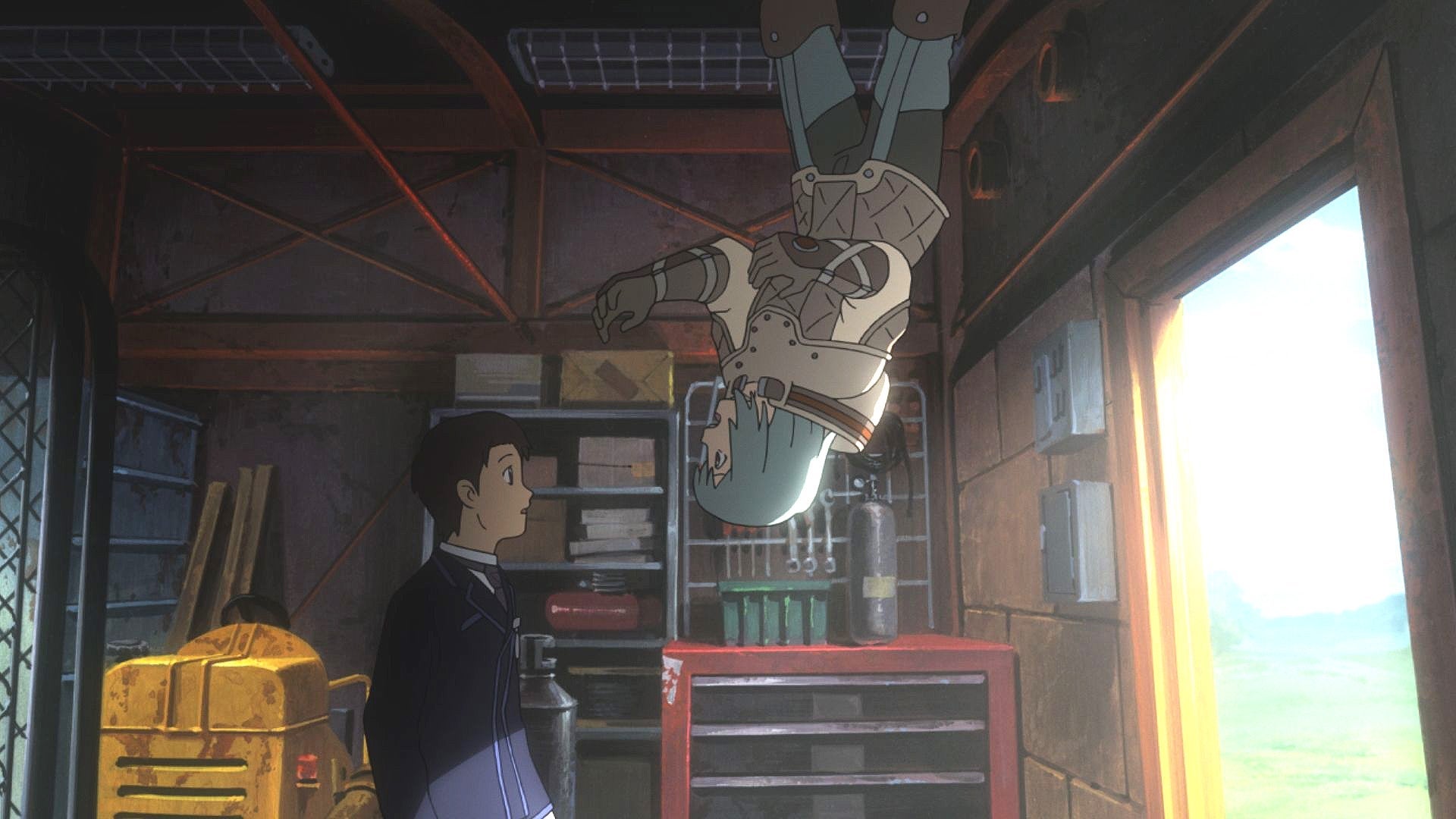

1 – Mirai: The first anime not produced by Studio Ghibli to receive a Best Animated Feature nomination at the Oscars, and deservedly so, Mamoru Hosada’s film depicts the struggles of a young boy whose busy parents have presented him with a baby sister. Mirai (named for the sister) proceeds to take the viewer on a visually stunning, time-tripping journey through the protagonist Kun’s family tree en route to a poignant and emotionally satisfying conclusion. It’s a family film that offers something very real to parents as well as children.

But it remains a battle to secure publicity and screenings for most of the medium’s large screen offerings, with the exception of Studio Ghibli, thanks to its partnership with Disney.

You might have thought the superhero-based My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising would have broken the mould, given, you know, Marvel, and that it was favourably reviewed by The New York Times. The latter picked up on the novelty of its unique selling point: heroes as public servants rather than vigilantes. However, most dismissed it as for hardcore fans only, where it even merited a mention.

“I grew up near Stranraer,” says Patridge. “The nearest cinema was in Ayr. To get to it you had an hour and a half over country roads dotted with speed cameras. With anime’s limited screenings, your chances of getting to see a new one if you’re at school or working and it’s, say, on a Thursday night, are slim. What we’re aiming to do is to make it more accessible.”

The festival also seeks to address the often lengthy gap between films’ cinematic releases and their debuts on home video, or streaming services. Complications with the rights mean this can be unusually long by comparison to western films. The momentum built up through a cinema screening is often lost through the film fading from consciousness.

“It does explain why anime often operates in a vacuum vs Hollywood studio in terms of timelines from theatrical to the next window,” he says.

This gap is all the more glaring at a time when the big Hollywood studios have made content available for early streaming, and art-house movies are making a splash through online releases via channels such as Curzon Home Cinema.

One intriguing development she’s noticed is that whereas once young people took up learning Japanese for the business opportunities it offered, now they’re as likely to be inspired by anime

The launch of the festival means those enchanted by Weathering With You’s sweet melancholy won’t have to wait as long as they might have feared. The festival will stream it from 22 June, in what counts as a notable coup. Priced at £3.95 a month, membership is cheaper than a typical premium Amazon rental, and below the monthly cost of most streaming services.

Rather than offering the sort of catalogue that Netlflix or Amazon Prime specialises in, content will be regularly refreshed and enhanced by commentaries, group screening sessions and the like. Ghibli’s arrival on Netflix can only help him if people who may have already seen Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro or one of the legendary studio’s other more famous releases dig deeper into the catalogue.

They will inevitably find other anime properties appearing when they log in, courtesy of Netflix’s notoriously capricious algorithm. It has a library of content produced in-house as well as non-Ghibli bought-in properties, ranging from sciifi, to slice of life, to coming of age, to ultra-violent martial arts pieces.

“There’s a manga for everyone,” the British Museum declared with its groundbreaking exhibition. The same is true of anime. Getting people to move beyond Ghibli’s admittedly outstanding catalogue remains the challenge for Partridge, and the medium’s other passionate advocates, who’ve been at the vanguard of its growth.

2 – Weathering With You

Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name is one of those still relatively rare animes to have been widely reviewed and relatively widely screened. Its follow up is, however, arguably the better, and braver film. Shinkai’s on familiar ground with adolescent romance, but there’s an element of gritty realism with his depiction of the struggle to survive faced by a young runaway on the streets of Tokyo, who is both aided and exploited by the main adult supporting characters. The grownups are, in general, more rounded and interesting in this film than in Your Name. Weathering shows the director is capable of challenging if not entirely leaving his comfort zone.

“Many people, when you ask what anime they like, they say Ghibli even now,” says Junko Takekawa, senior arts programme officer at the Japan Foundation in London. She’s keen to emphasise the world of content that exists beyond what the legendary studio has released. Justifiably so.

“There’s nothing wrong with Ghibli but there is room to push beyond Ghibli,” she says. “Anime is loved naturally by a younger audience and that is the way they get in, it’s a really huge gateway to get to know Japanese culture.”

One intriguing development she’s noticed is that whereas once young people used to take up learning Japanese for the business opportunities it offered, now they’re as likely to be inspired by anime, and manga, and the desire to appreciate them in their mother tongue.

But she says there’s more to be done.

Prior to the lockdown, the year’s first London Anime and Gaming Convention was a sellout. Among the cos-playing hordes, you were as likely to see Goku (Dragonball) gliding past with Sailor Moon as you were American pop culture icons like Deadpool (who nonetheless put in an appearance).

I think anime will arrive when people stop saying ‘I’m an anime fan’. Nobody says they are movie fan. Everyone just accepts that you like some form of movie

The wildly popular mystery boxes, a convention staple featuring merchandise from your chosen franchise, included offerings based on less well-known titles such as Cells at Work! in addition to the more obvious My Hero Academia, One Piece and Dragonball.

The knowledge base of fans committed enough to buy tickets would provide some comfort to Takekawa. It is both broad and deep. It’s been that way for a long time among western creatives, who have long mined anime’s rich seam with a view to providing inspiration for their own work. Without it, there would be no Matrix, which spawned an anime anthology that was of higher quality, and rather better received, than the sequels, especially the second.

Ditto Kill Bill. Quentin Tarantino even talked of an anime prequel to his pair of films, although nothing ever came of it.

Christopher Nolan’s mind-bending Inception was one of the most critically acclaimed action movies of the past decade. Some of the scenes in that film were very familiar to those who had already seen Paprika, the classic anime that predates it. It explores similar themes but is arguably bolder, braver and more thought-provoking.

3 – Sword of the Stranger

A wandering ronin with a dark past, a child pursued by ruthless enemies with a dark purpose, a brutal gaijin superman determined to test himself and defeat our hero? Tropes? Those familiar with samurai cinema will find this film overflows with them. It’s the execution that makes this anime a winner. The action sequences are superlatively executed, the artwork is gorgeous, the pacing pitch-perfect. It’s complemented by a superb score. If you’re looking for something to provide an escape, and who isn’t a the moment, Sword provides it.

Helen McCarthy, one of Britain’s foremost anime experts, made reference to this during the Barbican’s season, which sold out on five of the eight nights and saw its cinemas running at 84 per cent capacity during the course of the event. She expressed some frustration at the lack of attention, and credit, the film has received in the west.

McCarthy was there at the start, when the closest encounter most people had to the medium was seeing Battle of the Planets when they got home from school. Science Ninja Team Gatchaman was heavily edited for young western audiences. There were also several additions, including cutesy robot 7-Zark-7, who majored in exposition and comic relief. The resemblance he bore to Star Wars C3-PO was fairly obvious.

“I think anime will arrive when people stop saying ‘I’m an anime fan’. Nobody says they are movie fan. Everyone just accepts that you like some form of movie. I wonder if we’ll ever be there,” McCarthy says.

Her caution is understandable. She’s seen false dawns before; the enthusiasm generated by Akira, Manga Entertainment’s arrival and the outrage manufactured over what it was selling to mostly young, mostly male fans, which naturally only served to encourage them, the Best Animated Feature Oscar finally awarded to Ghibli after multiple nominations, courtesy of Spirited Away.

But progress has been made, and a lot of it is down to McCarthy’s determination.

There was massive ignorance. People were saying nobody would buy it. One thing about me is if you say something can’t be done I will never give up. So I just never gave up

“It was absolutely unknown when I started. I did it because nobody else was interested. The first time I saw anime I wanted the anime encyclopaedia (which she eventually wrote part of and edited). If I had been about to walk into Forbidden Planet and been able to take home the sort of haul you can get today, I wouldn’t have written an anime book. It was terrifically sloggy at first. I spent years calling publishers and was always told there was no interest.

“Nobody cared. I cared because back in 1981 I met a guy and he’s the guy I’m still with. I knew he was remarkable in many ways. He had not long returned with his friends from their graduation trip to Majorca. They went and they were overloaded by the sunshine, the colour, the food with that special Majorcan twist, and then one night they thought we’ll watch some TV and they sat around and watched an all-night giant robot cartoon marathon and their brains were blown apart.

“They had never seen anything like it. The didn’t know it was Japanese because it was dubbed but they rushed out and bought everything they could find, mostly toys and comics, because you couldn’t buy European video to play in UK. When I met him, he had masses of cool stuff and he said, ‘Look at this, it’s Japanese. You’ve never seen anything like it.’

“And I turned the pages of that Spanish book and even though I speak about six words of the language I could read the story from the pictures. I thought I have to find out some more about it.”

Hooked, McCarthy started looking for more, helped by the fact that she worked at the British Library, which had some books on world animation. “There was massive ignorance. People were saying nobody would buy it. One thing about me is if you say something can’t be done I will never give up. So I just never gave up.

4 – Paprika

Trippy visuals are par for the course with anime. Paprika’s are on a whole other level. Displayed to their best effect on a Barbican’s cinema screen last year, they still delight on home video. But Satoshi Kon’s picture, focusing on a psychologist who uses a device that allows her to enter her patients’ dreams, has much more than that going for it. Part speculative sci-fi, part psychological thriller, it’s a riot, brimful of big ideas, a clear and very obvious influence on Christopher Nolan’s Inception, which it mostly outshines.

“Ten years later we founded Anime UK magazine. That gave us a lift-off, a gathering point and some kind of credibility. Publishers were resistant when a complete stranger who had never written a book back then walked and said we’re going to break a new genre. Especially if you were female. The mag let us build the profile.”

Today, she’s wary of seeing a breakthrough, or an Animeaissance, despite the progress that’s been made and the growing number of people who prefer Japan’s great multimedia franchises to the ones America has spawned. “Last year was like a sugar rush, there was so much going on, you had mangakas (manga creators) whizzing in and out. It was great. But I’m not a great one for looking in crystal balls. I’ve seen too many tides come in and then go out,” she says. “I prefer to live in the present.”

That present has been made cloudy by Covid-19, let alone the future. Gali Gold, head of cinema at the Barbican, had planned to screen another rare anime film before the end of the year. That’s now, obviously, on hold, although she says the venue’s commitment to the medium remains.

I still don’t know if more people are accepting it or if it’s just that the same group that’s always accepted it is being more open about it

The exhibitions meant manga too, has been enjoying a notable upswing in popularity. But it had been showing notable growth before the British Museum gave it a shot in the arm.

There are reasons for thinking it may continue. The aforementioned Forbidden Planet, the cult entertainment chain, devotes a substantial amount of floorspace to it at its flagship London store. Currently closed, for obvious reasons, it nonetheless has one of the UK’s most comprehensive selections.

Jamie Beeching, head manga buyer, says he first started to notice a surge in increase back in 2016, with titles such as Tokyo Ghoul and Assassination Classroom in the vanguard. Today, My Hero Academia is regularly among not just the retailer’s top 10 mangas, but its top 10 sellers overall.

“The availability of anime has been a big help,” he says. “At first a lot of it was only available through illegal streams, with fan dubs and poor subtitling. But with sites like Crunchyroll, and especially Netflix, picking it up, it’s really helped out. My brother, for example, had not really been interested but then he picked up on One Punch Man and he was hooked.”

5 – Tokyo Godfathers

A Christmas story, focusing on a drunk, a transgender singer who loves him and a teenage runaway; there are so many ways Tokyo Godfathers could have gone wrong. As it is, Kon’s film manages to avoid most of them, notably the risk of descending into syrupy sentimentality. The most important supporting character is Tokyo itself, but it’s an entirely darker and grimier Tokyo than the one featured in Lost in Translation. In the midst of the characters chaotic, farcical, trip around Tokyo with an abandoned baby, it doesn’t shrink from depicting the harshness of homeless life in the midst of a wealthy city.

Manga fans traditionally cite popular titles’ immersive storytelling and accessibility as key to their appeal. Marvel and DC comics are part of huge, interconnected universes, with frequent crossover events. That can be daunting for the neophyte reader. Most mangas are unique unto themselves. Find one you like, jump in with the first tankōbon volume (independent volumes of a single manga), and away you go.

But Beeching thinks there may also be an economic motivator, which is of particular relevance at a time when Britain is staring down the barrel of a recession of historic proportions: manga offers value for money.

“Your average Marvel might be 150 pages for say £15. A manga can go for as little as £6.99 for 200 pages. It’s in black and white and the paper is cheaper but the price point is encouraging people in.”

Beeching also highlights another key strength: Manga does things, taps into markets, that western comics rarely approach.

“They cater to audiences that western comic books don’t. You have LGBT+ titles, romance mangas, and more besides.”

They also offer wildly imaginative storytelling that can prove attractive to people looking for something outside the big American mega-franchises.

Beeching cites Kodansha Comics’ Witch Hat Atelier, about a young girl who dreams of being a witch despite not being born with a gift for magic, and So I’m a Spider, So What, whose protagonist is reincarnated as a spider in a video world, as personal favourites. The latter, in particular, is a good example of the sort of story that isn’t easily found in comic books outside manga.

You look at the Academy Awards, there have been a couple of dubbed anime films that have been nominated for best animated feature

Takekawa is particularly keen to promote shojo (young teenage females) and josei (young adult) comics, which are aimed at female readers and which she thinks are underrepresented. The medium now even has a UK-produced magazine, the traditional way manga is consumed in Japan. Manga Big Bang was founded by Dr Vivian Wijaya, AKA Dr Vee, who abandoned a career in medicine to pursue her childhood dream of becoming a creator.

Voice actor Neil Kaplan is a veteran of numerous anime dubs. An Animeaissance, a boom in the popularity of Japanese pop culture generally, would surely benefit him. It’s been a reliable source of work.

“I still don’t know if more people are accepting it or if it’s just that the same group that’s always accepted it is being more open about it,” he says. “My father was born in 1938, the same year that Snow White came out, and I never understood, before he passed away, why there wasn’t any more adult dramatic animation.

“I don’t understand why that’s been accepted in the east but not so much in the west. Years ago when Universal was talking about rebooting their monster series I was one of those people who said I wish they would give us an R-rated digitally animated Wolfman. Something that could really play on the drama of the story and make use of the artwork.

“But I would say the art form seems to be gaining traction because you look at the Academy Awards, there have been a couple of dubbed anime films that have been nominated for best-animated feature, and there’s all the stuff on Netflix which wouldn’t be there if there wasn’t a demand for it.”

What’s certainly true is that the backdoor through which anime had been getting in is now open a lot wider. The market has expanded. Partridge, a skilled entrepreneur, readily admits that there are still many easier ways of making money than trying to sell anime. But he’s managed to do it, and he says he’s encouraged by the results from the festival’s marketing campaign.

“I’ve launched a few platforms. This is above those in focus and interest. Whether that converts… I don’t know. But we’re in this for the long haul,” he says.

The medium’s enthusiastic promoters all are. The Animeaissance may not be here yet, but it is coming.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments