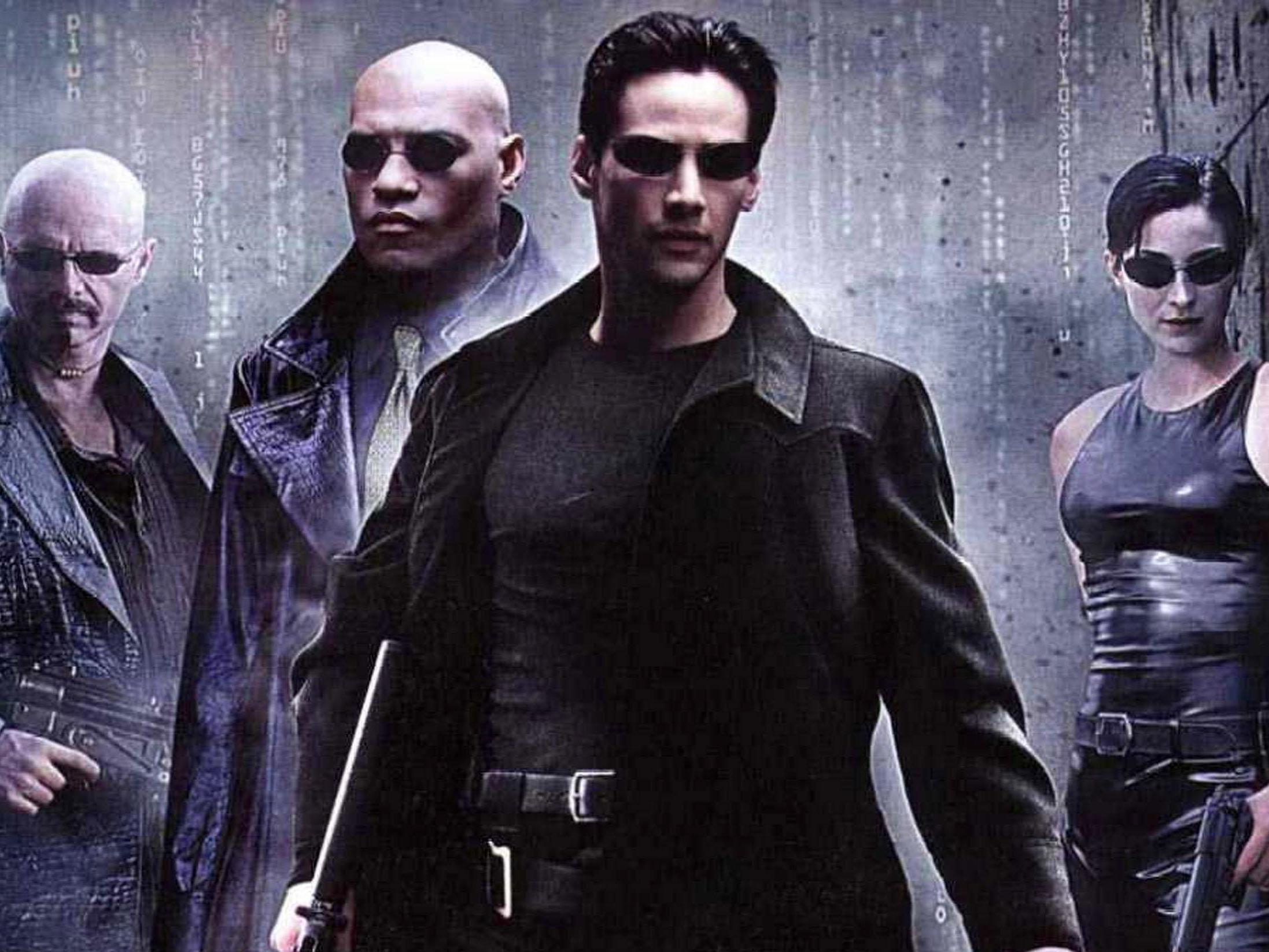

The Matrix at 20: How the Wachowskis' sci-fi masterpiece epitomises Nineties cinema

Jack Shepherd looks at a trend that proliferated some of 1999's biggest films

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Twenty years ago, The Matrix debuted in cinemas and broke our reality. The sci-fi action flick challenged us to question the nature of the world. Are we here? Or are we actually plugged into a computer mainframe that simulates the year 1999 – “the peak of civilisation,” as Hugo Weaving’s Agent Smith says – while an alien race uses our real bodies as organic Duracell batteries?

No film has had quite the same impact on pop culture since. “Red pill or blue pill?” is just one phrase that has become common parlance after the film popularised it. Cinematic techniques such as those slowed-down “bullet time” shots, and “wire fu” choreography, have become blockbuster staples. Leather jackets were never the same again.

The Matrix also spawned untold popcorn-munching debates about existence, with every viewer who saw Keanu Reeves’s Neo take that infamous red pill having something to add to the conversation. Strip away subtext, though, and the film becomes a different beast: a time capsule of Nineties cinema, where the most popular leading characters were desperate to escape the tedium of nine-to-five.

Before discovering the truth about The Matrix, Neo is an average computer programmer named Thomas Anderson who works a mundane desk job. The directors, the Wachowskis, make sure to show us the rows and rows of copy/paste cubicles that occupy his open plan office. It was a familiar setting to millions of Americans – the place where they spent their weekdays.

Through his side-hustle – hacking – Neo comes into contact with Lawrence Fishburne’s Morpheus. The ensuing scene sees Neo, at work, receiving a FedEx package with a phone inside. Morpheus, a prophet in mirror shades, is on the other end and reveals that Agent Smith is coming. The only way to escape is to climb down 30 storeys' worth of scaffolding. “This is insane,” Neo says. “Why is this happening to me?”

On a literal level, the scene shows a man, fed up with his monotonous life, getting an exciting call to adventure. It’s the setup to a thousand heroes journeys, but the Wachowskis very deliberately make Neo a white-collar worker, one who wears the same uniform – brown jacket, tie, top button undone – that, years later, Rickey Gervais’s David Brent would happily don on The Office.

The same archetypal everyman echoes through various other films released that year. Look at the Oscar Best Picture-winning American Beauty. Also released in 1999, the film is about an advertising executive called Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey) who despises his job. Instead of discovering a deceptive digital world created by intergalactic beings, Lester becomes infatuated with a young cheerleader. Their relationship soon breaks the uniformity of his life.

Then there’s Fight Club, another 1999 film regarded as a modern classic. Edward Norton plays an unnamed automobile recall specialist who finds a kindred spirit in Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) and the two start a fight club. They would rather beat the crap out of each other than continue their normal lives.

Neo; Lester; Norton’s unnamed car specialist: they’re three white Americans with steady jobs, disenchanted with their surroundings, and looking for somewhere, anywhere, to escape. This archetype remains absent from the vast majority of recent blockbusters, whose superheroes are more worried about the Earth’s safety than finding ways to spice up their lives. There are other examples from 1999, such as John Cusack's rundown puppeteer in Being John Malkovich. Perhaps the most obvious, though, is Office Space, the cult comedy that lampooned typical white-collar life.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

That desire to watch normal workers embark on tantalising adventures seems symptomatic of the time. In 1999, unemployment in the United States was at a near 30-year low. The Gulf War had finished almost eight years earlier, and the existential dread of another seemed far away. The biggest scandal the year before was Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. There was a general sense of ennui.

The events of 9/11, coinciding with the bursting dot-com bubble, changed attitudes to cinema. People no longer wanted bleak stories – the news was dark enough already – and people turned to light-hearted fantasy. The superhero boom started to take flight in 2002, with Spider-Man coming third at the box-office. Then, when the financial crash of 2007 happened, shows such as The Office US and, later, Parks and Recreation, were watched by millions of Americans. Both showed that having a job was no longer something to escape – but something to embrace.

Today, when sequels and reboot are blockbuster titans, reports have circulated that The Matrix could be coming back. Chances are, this time, whoever plays Neo will be looking to escape this reality for a whole host of other reasons – not just boredom.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments