Gottfried Leibniz: Is this the best of all possible worlds?

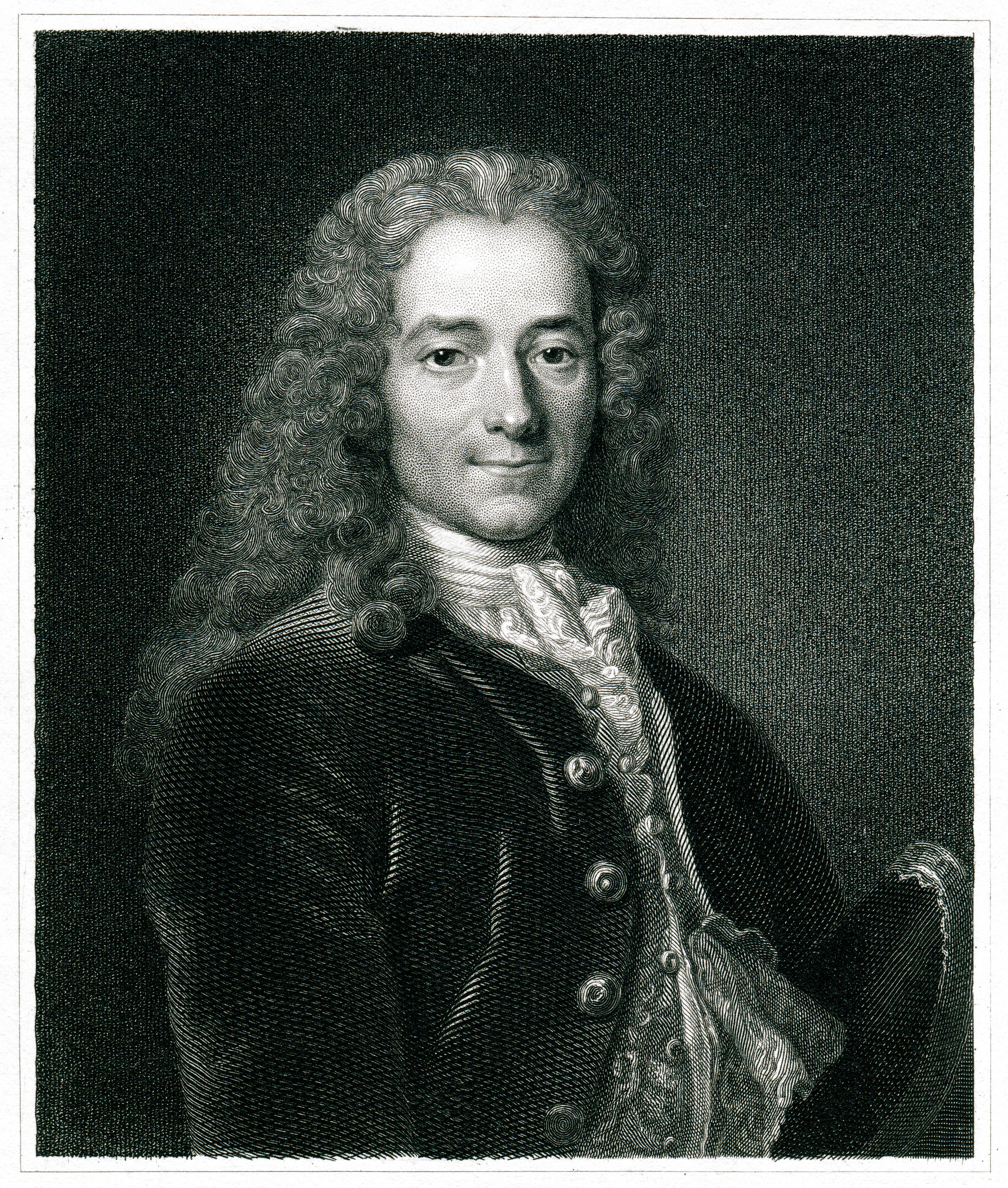

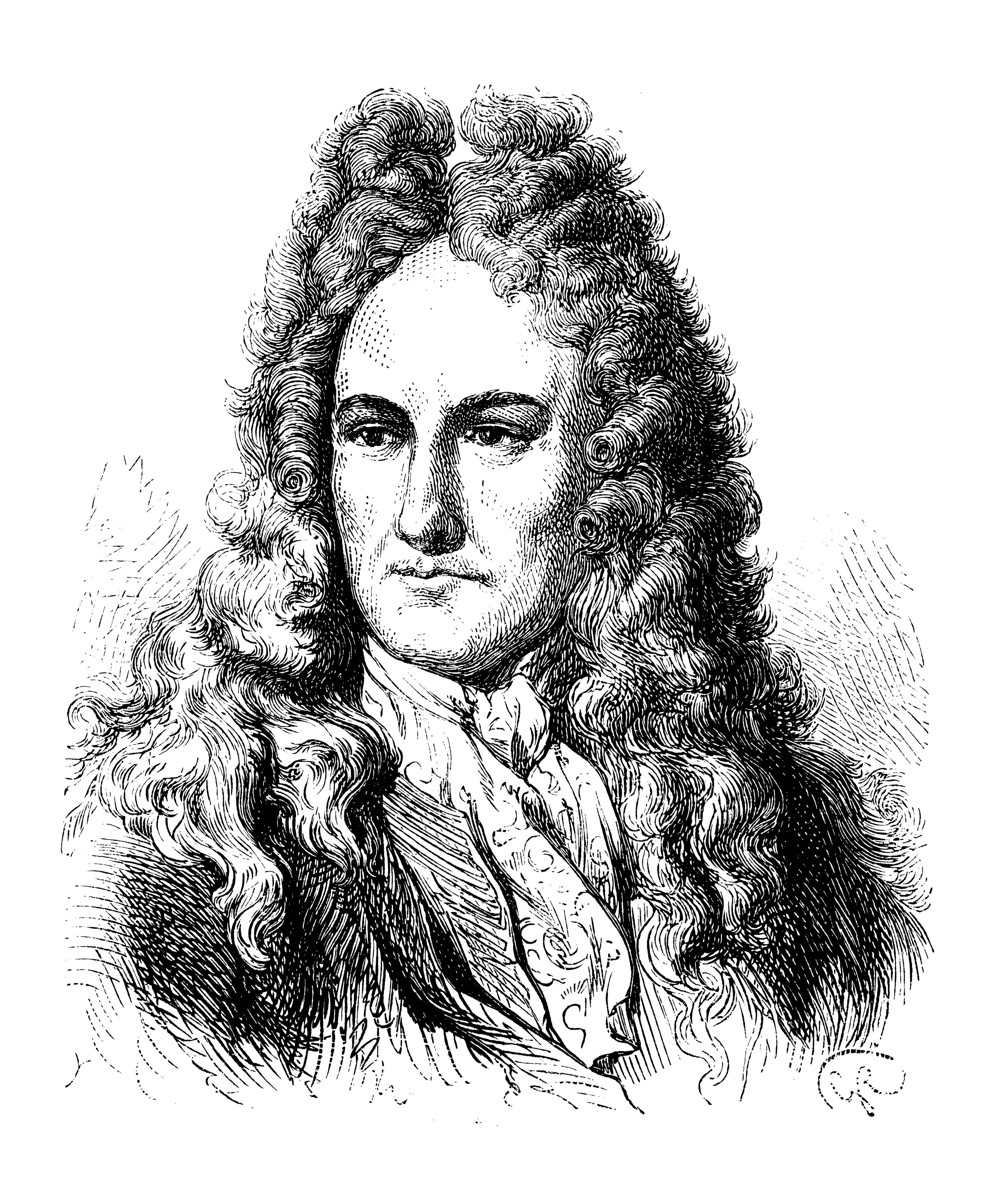

He was turned into a caricature by Voltaire but, far from being some sort of buffoon, he was in fact one of the leading intellectual figures of his age

Among his many achievements, Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) invented differential calculus independently of Isaac Newton; much of the notation and vocabulary used today comes from Leibniz, who possessed a flair for both symbolism and language. He was also a pioneer in the field of symbolic logic.

However, unhappily for Leibniz, he is probably best known as the inspiration for Voltaire’s satirical creation, Dr Pangloss, who spends his time in the novel Candide insisting that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds, despite the fact that he is confronted with disaster after disaster. There is an element of truth in this characterization of Leibniz’s philosophy – or his metaphysico-theologo-cosmolonigology, as Voltaire put it – but it would be a mistake to think that Leibniz was some sort of buffoon. He was one of the leading intellectual figures of his age.

He was born in Leipzig on 21 June 1646. His father, who taught moral philosophy at the University of Leipzig, died when he was only six years old, and he was raised mainly by his mother, who was careful to nurture and encourage his precocious intellectual talents. He taught himself Latin at an early age in order to read Livy, and then, having been given free run of his father’s library, worked his way systematically through the ancients – Cicero, Herodotus, Seneca and Plato.

Leibniz went off to university when he was only 15, first to Leipzig and then to Altdorf, graduating with degrees in law and philosophy. After receiving his doctorate in 1667, he was offered a professorship, but he declined it in favour of a diplomatic position at the Court of the Elector of Mainz. This decision was crucial to his intellectual development. In 1672, he was sent on diplomatic business to Paris, where he remained for four years, during which time he began to establish his reputation in European intellectual circles, meeting some of the leading thinkers of his day, including the mathematician Huygens, and the theologian and philosopher Malebranche.

During his time in Paris, Leibniz demonstrated his wide intellectual interests, laying down the foundations of differential calculus – independently of Newton – an achievement which would have recommended him to posterity even if he had done no important work in philosophy. He possessed prodigious ability in a number of separate fields. Like Blaise Pascal, he invented a calculating machine; he also designed various wind- and water-powered pumps, which were supposed to drain mines (unfortunately, they didn’t); and he did significant work in geology, physics and even history.

Possibly because of his wide range of interests, his philosophy was never laid down in systematic fashion. Indeed, he only published one book in his lifetime – The Theodicy – preferring instead to set down his philosophy across a series of short articles and in voluminous correspondence. It is, nevertheless, possible to identify a number of key themes in his work.

The best of all possible worlds

Perhaps the most important of these is the philosophical optimism which Voltaire satirizes in Candide. According to Leibniz, this world is the best of all possible worlds; to our modern minds – and, indeed, to Voltaire’s not-so-modern mind – this is a somewhat implausible idea, but Leibniz thought it could be deduced from the terms of a rationalist theology. Put simply, the ontological argument shows that God, the most perfect being, exists; since he is perfect, it is inconceivable that he might have made things better than he has; therefore, this world is the best of all possible worlds.

For to think that God acts in anything without having any reason for his willing, even if we overlook the fact that such action seems impossible, is an opinion which conforms little to God’s glory

Needless to say, this line of reasoning immediately raises a whole series of further issues. Even leaving aside questions about the ontological proof, there are problems with the argument. For example, it is possible that there is no best world, in which case God can only choose from an infinite series of worlds where each is better than the last. Leibniz rejects this criticism on the grounds that it compels God to make an arbitrary choice:

“For to think that God acts in anything without having any reason for his willing, even if we overlook the fact that such action seems impossible, is an opinion which conforms little to God’s glory. For example, let us suppose that God chooses between A and B, and that he takes A without any reason for preferring it to B. I say that this action on the part of God is at least not praiseworthy, for all praise ought to be founded upon reason which ex hypothesi is not present here. My opinion is that God does nothing for which he does not deserve to be glorified.” (Discourse on Metaphysics)

Perhaps more difficult for Leibniz’s optimism is the “problem of evil”. Stated very simply – though it has cropped up in various different forms – this holds that the evil which exists in the world rules out the existence of an all-powerful, loving God. The problem, then, for Leibniz is this: His argument is that a perfect God will create a perfect world; the trouble is that it is obvious that the world is not perfect; just consider the effects of the bubonic plague, for example; therefore, by his own lights, there cannot be a perfect God.

Leibniz was aware of this problem, and had a number of responses to it. For example, he argued that it is simply a mistake to suppose that it is possible to eradicate particular evils from the world and yet leave the rest of the world unchanged. Thus, for instance, whilst it might appear to us that the world would have been a better place without the Great Plague of 1665, we are actually in no position to make that judgement. He also questioned whether human happiness was necessarily the right measure for assessing the goodness of the world. As an alternative, he suggested that the best world is the one which is the “simplest in hypotheses and the richest in phenomena”; in other words, it is a parsimonious world.

Monads

“It is not only in the area of theodicy that Leibniz’s philosophical optimism makes its presence felt; it also makes an appearance in his famous metaphysical theory of substances. It was Leibniz’s view, certainly in the latter part of his life, that reality is constituted by an infinite number of unities, or monads. These are simple, non-divisible, soul-like entities which lack extension, spatial position, shape, or indeed, any physical characteristics. Leibniz puts it like this:

“The Monad … is nothing but a simple substance, which enters into compounds. By ‘simple’ is meant ‘without parts.’ And there must be simple substances, since there are compounds; for a compound is nothing but a collection or aggregate of simples … These Monads are the real atoms of nature and, in a word, the elements of things.” (The Monadology)

On the basis of this initial conception, Leibniz is able to deduce a number of other characteristics of monads. For example, he argued that they only exist and can only be destroyed by divine intervention; that they have no “windows” through which anything can come in or out, so they cannot be affected by the actions of other entities, which means that they must be the sole source of their own activity; and that they are endowed with perception and appetition (the principle by which their perceptual states change).

What then of inanimate objects such as computers, beds and books? Surely Leibniz didn’t think that these were built out of monads, which, after all, he thought were soul-like entities? The answer is that he did; but out of “bare monads”, rather than the self-aware monads, which are human minds. Liebniz’s view was that monads are arranged in an infinite hierarchy; God, as the supreme monad, is at the top; human minds do pretty well, as a result of their capacity for rational thought and self-awareness; bare monads, only marginally percipient at all, come in at the bottom.

No doubt this all sounds very bizarre, not least because there is the question of how things in the world interact with each other. Given that Leibniz believed that monads are unable to affect each other, how is it that bodies, which comprise aggregates of monads, seem to do just that? It is here that Leibniz’s philosophical optimism enters the picture. He argued that the regularities between monads were pre-established by a benevolent God; that monads were oriented towards each other in terms of a pre-existing harmony. To put this another way, it was Leibniz’s view that God had created the universe in such a way that the actions of any one monad will automatically be reflected in the actions of all others.

Leibniz’s standing as a philosopher took a while to grow. Partly, as has already been noted, he was damaged by Voltaire’s satirical treatment of his philosophical optimism in Candide; and partly the fact that his work was not published in a systematic way meant that it took a while for people to appreciate its full significance. However, with the publication of New Essays on Human Understanding, his book-length criticism of Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which was written at the turn of the 18th century but not published until after his death, his reputation began to grow. Today Leibniz is recognised as one of the greatest philosophers of the 17th century. Many of the concepts and ideas which are now a standard part of the philosophical armoury – for example, the principle of sufficient reason, the identity of indiscernibles, and possible worlds – were introduced or foreshadowed in his work.

In common with a number of other philosophers, the last few years of Leibniz’s life were not particularly good. In the aftermath of a row with the British scientific establishment over the originality of his differential calculus, he became embroiled in a bad-tempered correspondence with Samuel Clarke, a disciple of Newton, over the nature of space and time. Then, in 1714, his employer, Georg Ludwig, travelled to England to ascend the British throne but did not invite Leibniz to join him there, supposedly because he had not made sufficient progress in writing the history of the royal House of Brunswick. Two years later, on Sunday 14 November, Leibniz died in Hanover at the age of 70. He was buried a month later in an unmarked grave, which was hardly a fitting end for a man who had been celebrated in his lifetime as one of the 17th-century’s greatest intellectual figures, and who would come to be recognised as one of the world’s great philosophers.

Major works

Gottfried Leibniz only published one book in his lifetime, The Theodicy, preferring instead to set down his ideas in a series of short articles and voluminous correspondence. The Cambridge Companion to Leibniz is a good starting point to get a sense of this work; it also includes an essay by Roger Ariew, detailing Leibniz’s life and works.

The Theodicy (1710)

Subtitled Essays on the goodness of God, this work is primarily a defence of Leibniz’s philosophical optimism as it relates to God. In particular, it contains a sophisticated response to the “problem of evil”.

The Monadology (1714)

Not published until after his death, this is a short outline of Leibniz’s view that reality is constituted by infinite number of unities or monads. These are simple, non-divisible, soul-like entities, which lack extension, spatial position, shape, or indeed, any physical characteristics.

New Essays in Human Understanding (1765)

Written at the turn of the 18th century, but not published until some 50 years after Leibniz’s death, this work is a detailed, critical discussion of and response to John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments