The mirror effect: What happens when filmmakers tell their own most intimate stories on screen

As Steven Spielberg shoots ‘The Fabelmans’, a movie about his own childhood and adolescence, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the best autobiographical films and how successfully directors have distilled their innermost experiences

George Lucas did it with American Graffiti (1973), looking back at his teenage years, when he and other adolescent young bucks would cruise the streets of early 1960s Modesto, California, in their souped-up cars. They’d listen to rock and roll and try to pick up girls while fretting inwardly at what adult life might hold.

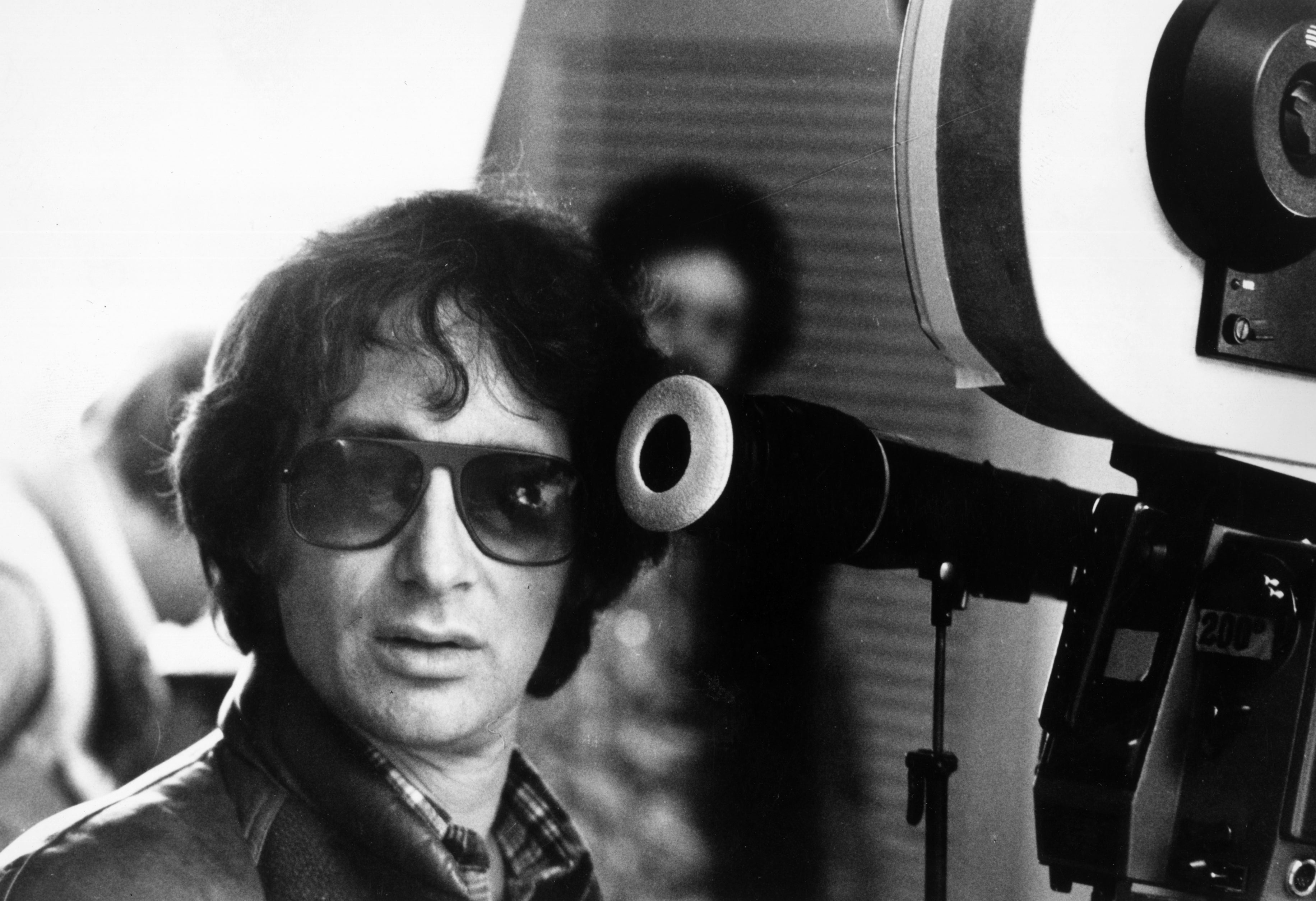

Now, towards the end of his career, as he approaches 75, Steven Spielberg is pulling the same trick, turning in on his own life for inspiration. This summer, Spielberg could have been directing the latest Indiana Jones movie. Instead, he has left that task to fellow director James Mangold while he begins work on The Fabelmans, based on his childhood and adolescence.

Books about him portray the young Spielberg as a Napoleon Dynamite-like kid, a mediocre student at his high school in Phoenix, Arizona. He didn’t excel either on the sports field or in the classroom. However, once he started making home movies, like his Second World War short Fighter Squad or his feature-length sci-fi adventure Firelight, his youthful genius and hustling skills were immediately apparent.

“It’s a wonderful story of this kid, this amateur filmmaker who teaches himself to make films from the age of 10,” says Spielberg’s biographer, Joseph McBride. “People don’t realise he has been making films for 64 years now, since 1957. By the time he made his first professional film, Amblin, in 1968, he had already been making films for 11 years.”

Spielberg’s parents were his willing accomplices. His father Arnold, a brilliant electrical engineer and computer pioneer who died last year at the age of 103, paid for the equipment and gave him technical tips. His high-spirited concert pianist mother Leah, who died in 2017 aged 97, helped him bunk off school by pretending he had a temperature. The young Spielberg shot scenes in the local hospital and persuaded American Airlines to lend him a plane for 10 minutes – not a favour they generally granted to teenagers bunking off.

In the new film, Michelle Williams is cast as the protagonist’s mother, Paul Dano as the father and Seth Rogen as a favourite uncle. Gabriel LaBelle plays the teenage hero.

It will be intriguing to see how Spielberg, who has co-written the screenplay with Tony Kushner, treats his growing pains on screen, whether he accentuates the comic aspects or portrays himself as a suffering young artist, taking on a hostile world. There is plenty of material in his backstory for both approaches.

Alongside his youthful feats as “Cecil B DeSpielberg”, as his mum nicknamed him, there was plenty of anguish, too. When the family moved to California, Spielberg endured some wretched times at Saratoga High School. This was when he was subjected to his worst antisemitic bullying. It was also when his parents broke up after his mother fell in love with his father’s best friend, Bernie Adler.

“I didn’t have a lot of high esteem for myself. Growing up, I was just a lonely guy,” Spielberg confessed in Susan Lacy’s 2017 HBO documentary about him.

“He was being persecuted for being Jewish and so he very cleverly turned the persecutors into collaborators on his films. There was a kid who was bullying him so he made him play Nazis and other heavies… Steven could boss him around,” McBride recalls of how Spielberg neutralised his enemies.

The biographer remembers interviewing one of Spielberg’s Phoenix classmates who marvelled at the young director’s authority on set. “This kid said, ‘Here’s this nerd whose head you would push into the toilet at school and he was commanding and in charge.’”

Autobiographical movies remain relatively rare, especially in Hollywood. Even the most egotistical directors seldom make movies based directly on their own lives. There is a long tradition of coming-of-age stories, which encompasses films such as This Boy’s Life (1993) and Stand By Me (1986). High school experiences have fuelled countless teen movies, while various features (invariably made by male directors) have looked at the antics of testosterone-driven pals on the cusp of adulthood and busy sowing wild oats. Barry Levinson’s semi-autobiographical Diner (1982) is one of the most celebrated.

Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous (2000) was inspired by his experiences as a young journalist writing for Rolling Stone while Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979) was based closely on the period in Fosse’s life when he was trying to stage an ambitious Broadway musical at the same time he was editing a big-budget movie – and was driving himself to distraction in the process.

Comedians often base their films around exaggerated comic versions of themselves. Amy Schumer claimed that Trainwreck (2015), which she scripted and Judd Apatow directed, was “pretty autobiographical”, even if her alter ego on screen, also called Amy, had more sex and drank more alcohol than the real-life version did.

However, Hollywood frowns on too much introspection. Directors who want to address their own demons or formative experiences in studio movies must do so in oblique and subtle fashion. Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and ET are packed with autobiographical elements – kids as lonely as he once was, families falling apart just as his own one did. He regarded his early TV movie Duel as an allegory about bullying and identified closely with the car that was being chased off the road by the monstrous truck. “The camera was my pen. I wrote my stories through the lens,” he once said, acknowledging the deeply personal nature of his work.

McBride suggests that “when he finally got around to doing Schindler’s List, it was a leap forward for him to deal with his Jewishness, which he had kind of avoided in his life and his work for a long time because he wanted to fit in.”

Spielberg’s entire career, then, can be seen as an exercise in closet autobiography. But openly autobiographical films are far more likely to be made by European art house directors. British filmmakers like Bill Douglas, with his trilogy beginning with My Childhood (1972), and Terence Davies, with works like Distant Voices Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992), have drawn directly on their tough working-class childhoods. More recently, Joanna Hogg, from a much more privileged background, has revisited her youthful experiences as a would-be filmmaker in The Souvenir and The Souvenir II.

François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), one of the films that launched the French New Wave, was “autobiographical down to the last detail” (in the words of Truffaut’s biographers Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana). That truculent boy Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Leaud), playing truant from school, was a near-replica of Truffaut, even if the director did try to pass his film off as fiction and set it in the 1950s instead of the Occupation years, when he had actually grown up. Truffaut realised that the more specific and authentic his approach, the more universal the film would become.

Autobiographical elements also seep into many of Federico Fellini’s films. Amarcord (1973) took a comic and surrealistic view of his childhood. I Vitelloni (1953), about the seediness and boredom as well as the pleasures of small-town provincial life, was partly inspired not only by Fellini’s experiences but those of his co-writers, Ennio Flaiano and Tullio Pinelli. Those writers also collaborated on the screenplay for Fellini’s most autobiographical film, 81/2 (1963), about a director very like Fellini (even if played by Marcello Mastroianni) struggling to make a film.

When the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky made Mirror (1975), he took a deliberately dreamlike and impressionistic approach. His poet father’s verse featured prominently on the soundtrack. The director was obsessive about recreating the countryside he remembered from his childhood. He planted buckwheat a year before shooting began so the fields would look just right, and recreated the old family bungalow so it looked exactly as he remembered. Mirror is arguably the most purely autobiographical film in cinema history. It is beautiful and very evocative, but also subjective, fractured and hard to follow. The director is treating his past experiences on screen in the way that a lyrical author might in some poetic stream-of-consciousness novel.

No Hollywood filmmaker would get away with such levels of indulgence. Instead, they have to smuggle personal elements into their movies through the side door. That’s why the surprise about the autobiographical nature of Spielberg’s next film is so misplaced. This isn’t really a new departure at all. In every film he makes, he is one director who has always held up the mirror to his own life.

Joseph McBride’s biography of Steven Spielberg is available from Faber & Faber. Susan Lacy’s HBO documentary ‘Spielberg’ is available on Amazon. Spielberg’s ‘West Side Story’ is due to be released on 10 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments