How Matt Damon and Ben Affleck conquered Hollywood

The power players used to sleep on each other’s sofas and couldn’t land a decent role between them. As they launch their own new $100m production company, Geoffrey Macnab looks at their meteoric rise, and says their indie credibility withered long ago

At the 70th Academy Awards in March 1998, craggy Hollywood old-timers Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau announced that a brand new double act, Ben Affleck and Matt Damon, had won the Best Screenplay Oscar. Affleck and Damon looked delighted but utterly terrified. “I just said to Matt that losing would suck but that winning would be really scary – and it’s really, really scary,” a bashful Affleck confessed on stage.

They were “just two young guys” who came from nowhere and had, all of a sudden, landed on top of the world. Even as Hollywood embraced them, they remained keen, though, to burnish their independent credentials.

“The mainstream sucks, and it always will, is the bottom line. Because they don’t understand how to make movies,” Damon is quoted as saying in Peter Biskind’s Down and Dirty Pictures, his 2004 book about Miramax, Sundance, and the rise of US independent cinema.

Those words seem a little rich now, after Damon and his childhood pal Affleck have just announced they’re going into business with a multi-millionaire financier, Gerry Cardinale of RedBird Capital Partners, to launch a new production company Artists Equity. It all sounds very white-collar corporate: Affleck will be chief executive with Damon as chief creative officer.

There was a very brief period in the 1990s when Damon and Affleck did indeed seem like the perfect indie movie brats. They were Cambridge, Massachusetts kids, not quite from the wrong side of the tracks – Damon went to Harvard – but they didn’t have it easy in their early days in the film business. The story of how they made their Oscar-winning breakthrough film Good Will Hunting (1997) has long since passed into movie myth. Like Sylvester Stallone in his pre-Rocky period, both were struggling actors who couldn’t land a decent role between them. They used to sleep on each other’s couches.

“The script was really born out of frustration at unemployment,” Damon admitted to the Today TV show at the time of the film’s release. “We wrote it pretty much out of desperation.”

The success of Good Will Hunting shunted them both into the mainstream where they’ve remained firmly lodged ever since. Their disgraced patron Harvey Weinstein, the former Miramax boss and the first name they acknowledged in their Oscar speech, is languishing in jail, convicted of rape and sexual assault.

The Miramax boss is a problematic figure in the rise of Damon and Affleck. It’s an uncomfortable coincidence that She Said, Maria Schrader’s dark and intense new drama about the two New York Times journalists Megan Twohey (Carey Mulligan) and Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan), whose investigative reporting toppled Weinstein, is hitting cinemas just as the two actors are announcing the new company.

Damon and Affleck became successful because of their own exceptional abilities, both as writers and actors, and because of their charisma – but nobody can deny that Weinstein’s early support turbo-charged their careers. In the mid-1990s, they were Weinstein’s golden boys. Just as they were emerging as stars, young female employees at Miramax like Zelda Perkins and Laura Madden, played by Samantha Morton and Jennifer Ehle in Schrader’s film, were having their lives ripped apart by their predatory boss. There are devastating scenes late on in She Said in which Perkins and Madden tell the reporters that “I feel completely broken” and “it was like he [Weinstein] took my voice”.

Weinstein had gambled on Damon and Affleck after rival company Castle Rock had put their Good Will Hunting screenplay into turnaround. They were his acolytes. As trade paper Variety put it in 1995, when he signed them up, they became part of the “Commedia del Weinstein” alongside other young filmmakers in the Miramax stable like Kevin Smith and Sean Penn. He had paid a fortune to acquire the script and allowed its writers to act in the film, in spite of them being unknowns. As Biskind wrote, everyone else wanted “Leo [DiCaprio} and Brad [Pitt]” to play the roles that Damon and Affleck eventually took.”

“Immediately, we loved him [Weinstein]. He pulled the trigger,” Affleck told Biskind about their delight when their movie was finally greenlit. Eventually, after failing to get Chris Columbus of Harry Potter fame, Weinstein agreed to Gus Van Sant directing the film. Thanks to Van Sant’s contacts, Robin Williams, then at the height of his fame, came on board. In spite of his reputation as Harvey “Scissorhands”, Weinstein is said not to have interfered in the editing.

Around this time, Damon had been cast in a leading role in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rainmaker (1997). Affleck was a former child actor who had already done movies with Richard Linklater and Kevin Smith. They were both on an upward curve anyway. Nonetheless, Weinstein was the Svengali behind the rapid rise of the two young hopefuls. By allowing them to make Good Will Hunting, he gave them the keys to the kingdom.

Their story about a janitor who turns out to have a genius for maths began as a one-act play that Damon wrote as a college assignment. The teacher liked it enough to urge him to keep on going. Affleck later weighed in as co-writer.

Damon excels as Will Hunting, the “boy genius from Southie [south Boston]”. He has both the youthful good looks and the abrasiveness needed for the part. Affleck is good value too in the supporting role as Chuckie Sullivan, his delinquent, doggedly loyal but dim-witted friend. Nonetheless, 25 years on, Good Will Hunting seems like a film with a soft centre and a very mainstream sensibility. The story combines scenes set on the mean streets of Boston with ideas that looked as if they have been taken from a sepia-tinted adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. Will is an orphan who acts tough around his pals in Boston’s bars and is in constant trouble with the cops, but he spends all his spare time reading books on maths, politics, and history. There are some maudlin moments involving Dr Sean Maguire, the therapist – Robin Williams at his most heartfelt – trying to help Will exorcise his demons.

No one is going to mistake Damon’s Will for James Dean’s Jim Stark in Rebel without a Cause (1955). Will is a clean-cut, level-headed, well-spoken figure who never really looks as if he is going to go off the rails. This wholesomeness is the secret of Damon’s lasting appeal, but also arguably what limits him. On screen, he is reliable and trustworthy, not someone you think of as neurotic or narcissistic. In his subsequent movies, he would very rarely be cast either as villains or as characters experiencing breakdowns. Whether stuck on Mars in 2015’s The Martian, playing Jason Bourne in The Bourne Identity movies, or confronting enemy fire on Omaha Beach in Saving Private Ryan (1998), he always seems ready to front up. Damon was so effective as the anti-hero in Patricia Highsmith adaptation The Talented Mr Ripley (1999) precisely because the casting was so unexpected. He could make even a serial killer seem like a boy-next-door type.

Since Good Will Hunting, the two actors’ careers have run in parallel. They’ve only occasionally appeared on screen together again, but both have shown extraordinary durability and resilience. They worked several times subsequently with Weinstein, on films from Rounders (1998) and Reindeer Games (2000) to Dogma (1999) and Bounce (2000). It was noticeable that Weinstein was far less supportive of Minnie Driver, their female co-star in Good Will Hunting. She received an Oscar nomination for her role as Skylar, the sharp-witted Harvard student who Will falls in love with. The producer, though, tried to have her replaced on the grounds she wasn’t “sexy” enough.

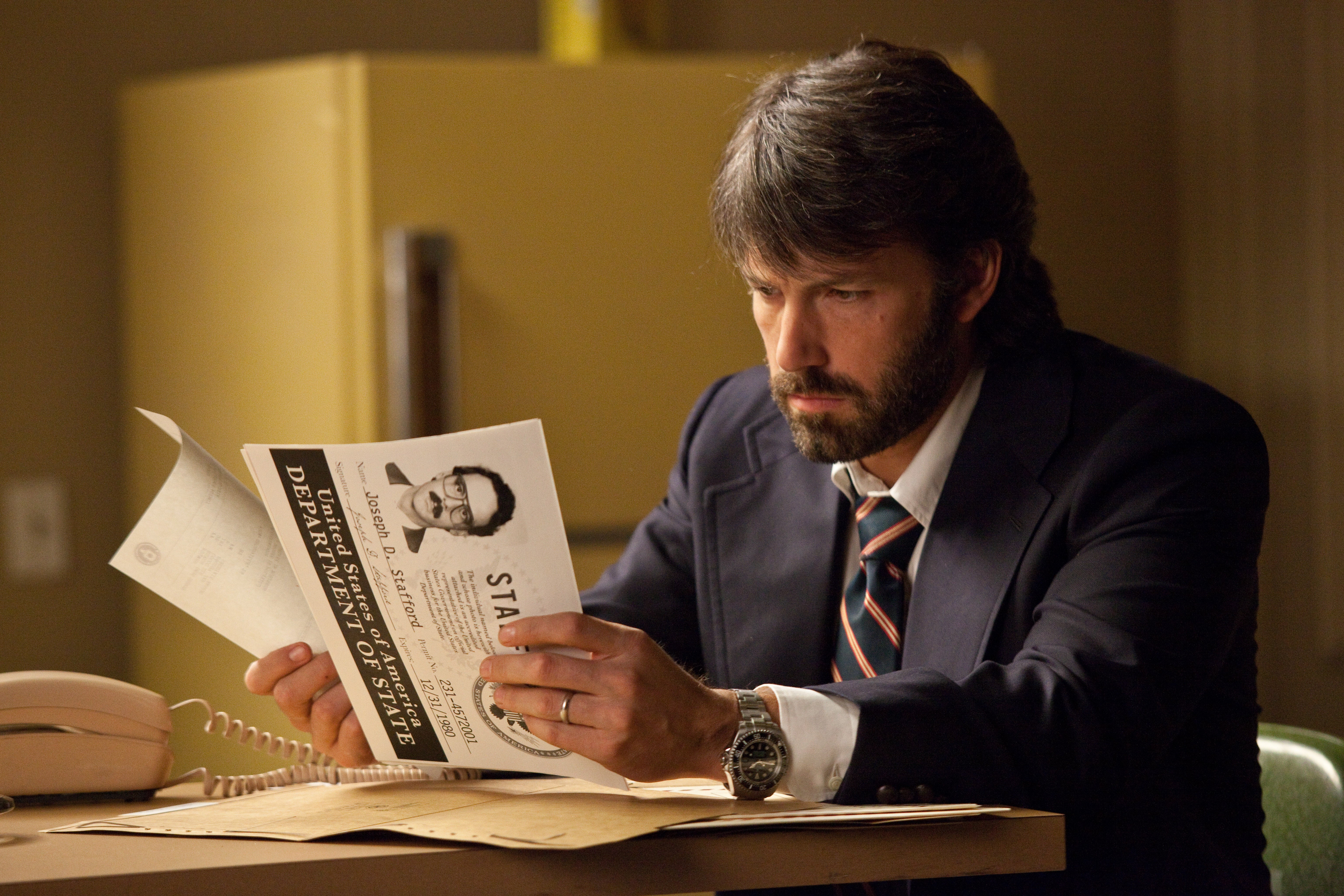

Affleck has survived regular brushes with scandal in his private life – affairs, divorce, accusations of sexual harassment – and the occasional box office disaster. He has made multiple comebacks. There have been some debacles along the way, most notoriously Gigli (2003), his romcom with Jennifer Lopez, which is bracketed by many critics as among the worst movies ever made. Pearl Harbour (2001) didn’t help his reputation either. More recently, his handsomely made but very torpid period crime drama, Live By Night (2016) lost a fortune at the box office. Set against such catastrophes, which might have torpedoed the careers of other, lesser actors, he’s had huge successes: the Oscar-winning Argo (2012), which he produced, directed and starred in and Gone Girl (2014), in which he was well cast as the hapless husband accused of murdering his wife. Whether playing Batman in a huge-budget superhero movie or the recovering alcoholic who coaches a high school basketball team in Finding the Way Back (2020), Affleck still has that south Boston underdog mentality first seen in Good Will Hunting.

Meanwhile, Damon remains among the most reliable and versatile stars of his era, switching genres with ease and giving solid performances. He too has overcome everything from diversity rows to criticism of his close links with Weinstein.

Their new company Artists Equity is the latest in a very long line of schemes designed to wrestle the power away from studio accountants. The rhetoric about the initiative is very familiar. According to trade publication Deadline, this is yet another “artist-led studio that partners with filmmakers to empower creative vision and broaden access to profit participation”.

During the streamer era, it’s a familiar complaint that the big VOD companies seize intellectual property rights and reduce artists to the status of hired hands. With their now very deep pockets, Affleck and Damon will be able to help their filmmaker partners hold onto their rights and thereby share in the profits when they make hit movies or series.

As the New York Times reports of the Good Will Hunting duo, together their films have generated “$10.7bn at the global box office” and they have three Oscars between them. That’s an impressive haul but it underlines what mainstream figures they have become. Any indie credibility they had withered long ago when they first joined the Miramax stable. They can’t be blamed for Weinstein’s misdeeds but nor can they ignore his role in their success. Now they’re the ones pulling the purse strings. Their new business-oriented priorities are reflected in their choice of material. According to the New York Times, Affleck and Damon, alongside Alex Convery, have co-written the screenplay for a new drama about the salesman who signed basketball legend Michael Jordan to a Nike sneaker deal. Now that’s not a movie that James Dean would ever have wanted to star in.

‘She Said’ is out on 25 Nov

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

3Comments