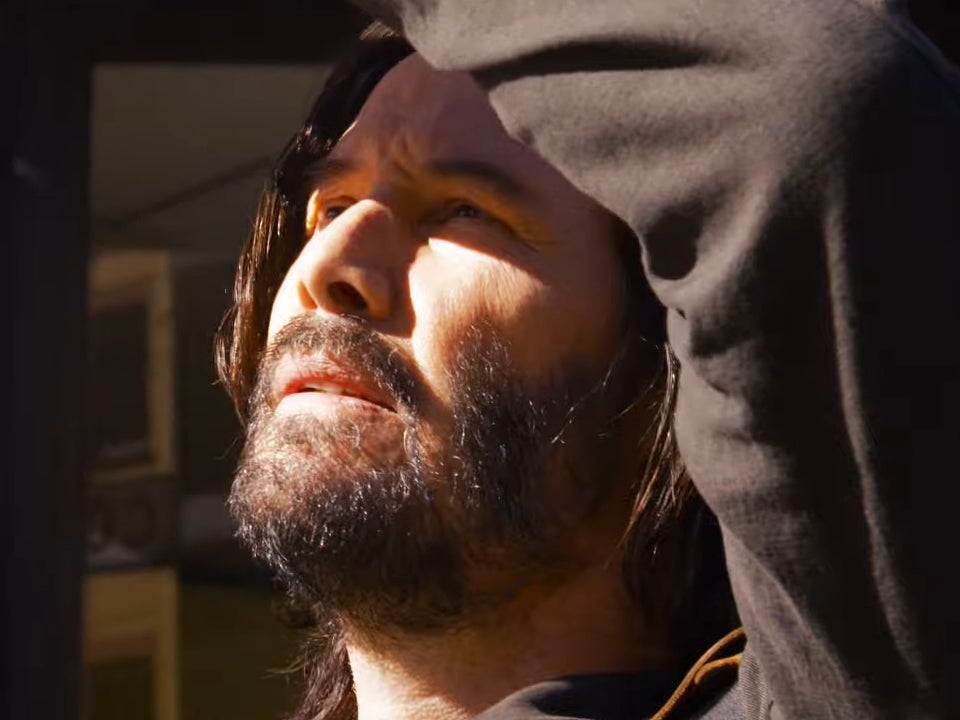

Why Keanu Reeves shouldn’t be underestimated

The star, who is reprising his role as Neo in Lana Wachowski’s ‘The Matrix Resurrections’, the fourth instalment of the Matrix franchise, is one of the most unfairly maligned stars of his era, says Geoffrey Macnab, who looks back over a 30-year career

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is 30 years since the moment in Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break (1991) when a senior FBI detective expresses his contempt for the young special agent Johnny Utah, played by Keanu Reeves. “You’re a real blue flame special, aren’t you, son,” the detective sneers. “Young, dumb and full of cum.”

The line stuck to Reeves. The Canadian was held in low esteem by many movie critics. Early in his career, he racked up Golden Raspberry nominations for the “worst performance” of the year.

Nonetheless, a strong argument can be made that Reeves is actually one of the most unfairly maligned stars of his era, an actor with a flair for both action and comedy, and with a far wider range than his detractors have claimed. He proved early in his career that he could move easily from the comic schtick of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) to playing existential loners and questing heroes in films like Point Break and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha (1993).

“His type of acting has always been a little bit awkward,” Jan de Bont, who directed him in the bomb-on- a-bus box office hit, Speed, once said of him – but meant it as a compliment. Reeves isn’t the fast-talking, self-assured macho character typical of other Nineties action films. He had a halting, introspective quality, even a shyness, which makes him far more appealing and intriguing.

Reeves has outlasted almost all his Nineties rivals. He’s now back on screen in Lana Wachowski’s The Matrix Resurrections, the fourth instalment of the Matrix franchise, again playing the mythical character Neo and again popping those very strange pills. He continues to strike box office gold in his John Wick thrillers. Now in his late fifties, he is accepted by a younger generation who don’t remember his action movies of the 1990s, while still being regarded with nostalgic affection by an older audience who saw him first time round surfing, robbing banks or at the wheel of a runaway bus.

Some of Reeves’s contemporaries, such as Patrick Swayze, have died. Others like Johnny Depp have seen their reputations crumble amid controversy and scandal. Reeves’s name, though, remains largely unblemished, both on screen and off.

The actor’s detractors often point to Johnny Mnemonic (1995), a futuristic sci-fi thriller that is set in the year 2021 – and doesn’t do that bad a job at imagining reality as we experience it today.

“From his robotic delivery you’d never guess that he’s meant to be a flesh and blood man,” The New York Times wrote of the star. In the film, he plays a courier for the mob, who has a day to get rid of the memory chip in his brain or he will explode. It isn’t remotely a convincing performance, but that has as much to do with the stilted filmmaking as with any inherent deficiencies in his acting. If you want to see Reeves in a high-concept sci-fi movie, it is much better to turn to the first Matrixfilm (1999), in which he excels. It’s not just his charisma as Neo, accentuated by those shades and long black leather coats. More importantly, Reeves is the point of entry into the Wachowskis’ mind-bending, maze-like universe. With a less sympathetic lead, the film could easily have been incomprehensible and deeply pretentious.

It was Reeves’s misfortune that he quickly turned into a pop icon. In the UK, The Modern Review, the irreverent “low culture for highbrows” magazine founded by journalists Julie Burchill and Toby Young, put him bare-chested on the front cover with the “young, dumb and full of come” line in bold type as the headline. They claimed they admired him, but there was something inherently condescending in their approach. They were treating him as a male bimbo, as eye candy for media studies students.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

In this period, Reeves was doing some of his best early work, notably in Point Break and Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991), in which he played a street hustler. He was also far bolder in his choices than was widely acknowledged, ready to try his hand at everything from Shakespeare adaptations (a bad idea as it turned out) to vampire movies (he was superb as the romantic lead Jonathan Harker opposite Gary Oldman’s bloodsucking Count Vlad in Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation, Bram Stoker’s Dracula).

Bigelow deserves credit for realising Reeves’s potential as an action movie star. She saw he had the screen presence to play the FBI agent in Point Break. She reportedly had to fight hard to get very sceptical studio bosses to cast him. “He’s the guy,” she insisted.

Reeves was the 1990s equivalent to those epicene movie stars of the 1940s and 1950s, like Audie Murphy and Montgomery Clift, who turned out to be surprisingly effective in westerns and war movies. He wasn’t one of those rugged, ultra-macho Lee Marvin types. He had a sensitivity they lacked. That was the whole point. He wasn’t a thug. Even in the darkest roles, he retained his boy-next-door quality.

Reeves is indeed a consummate screen actor. From the beginning of his filmmaking career, he understood that less was more. His movie characters rarely betray emotion. In John Wick, the protagonist reacts to the killing of his beloved dog in the same way Clint Eastwood’s characters used to react to the deaths of their nearest and dearest in spaghetti and civil war westerns. That’s to say, he suppresses and bottles up the grief. The less feeling he shows, the more the audience understands the sheer magnitude of his bereavement.

You can easily understand why Reeves was chosen to narrate the 2015 documentary, Mifune: The Last Samurai, a hagiographic account of the life and times of the great Japanese star, Toshiro Mifune, of Yojimbo and Seven Samurai fame.

“Without him [Mifune], there would have been no Magnificent Seven. Clint Eastwood wouldn’t have had a fistful of dollars and Darth Vader wouldn’t have been a samurai,” Reeves intones in his voiceover. “He [Mifune] pursued two of his favourite hobbies, cars and alcohol, often at the same time.”

Reeves could easily have added that his own career might not have developed in the way it did, had Mifune not first created the template for the modern-day action hero. Keanu, though, has qualities that Mifune lacked. He is far more laid-back on screen than the tightly wired Japanese star. He also possesses an inscrutable quality which many of the great movie stars have shared. We’re not sure what he is thinking. His face is a canvas on which viewers can project their own innermost feelings.

Nor has Reeves ever been consigned to the twilight world of formulaic B movies inhabited by other action stars like Nicolas Cage and Liam Neeson. The John Wick films may be clichéd in plot terms, but they’re made on healthy budgets and feature extravagant, very elaborately choreographed stunts. They are all about movement and spectacle. They allow Reeves to display his balletic grace, another quality that critics often overlook.

Watching him glide elegantly through a series of ever more perilous situations, you realise he is an action hero more in the tradition of silent stars like Douglas Fairbanks in his Zorro-mode, than of mastodon-like contemporaries like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

These days, Reeves doesn’t just appear in action films and reboots of the Matrix series and Bill & Ted. He has produced intriguing documentaries, such as 2012’s Side By Side, about the move in filmmaking from celluloid to digital, and has directed a movie, 2013’s Man of Tai Chi. You underestimate him at your peril. As its title suggests, the Matrix franchise may need resurrecting, but Reeves comes into the film from a position of strength. The FBI detective who mocked him in Point Break was way off the mark – and so are all those grudging reviewers who’ve been belittling him since Bill & Ted days. He wasn’t dumb then and he isn’t dumb today. Maybe now, 68 films and more than 30 years into his “most excellent” career (as Bill and Ted might call it), he’ll get the respect he deserves.

‘The Matrix Resurrections’ is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments