John Wayne: The toxic legacy of one of Hollywood’s most beloved stars

As the new Tom Hanks film News of The World pays tribute to the controversial Wayne western The Searchers, Geoffrey Macnab asks if the actor’s work can still be enjoyed today

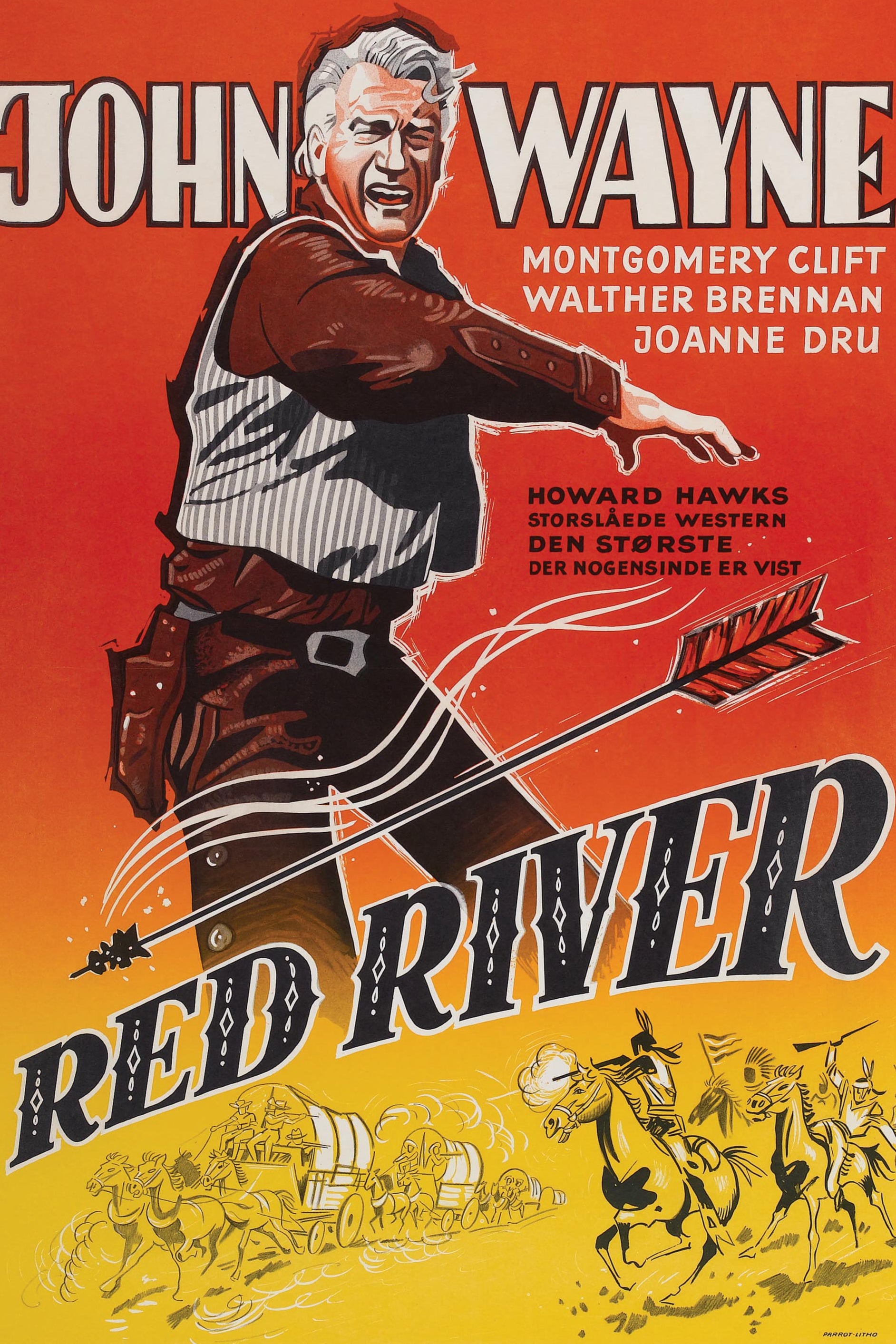

These are uncomfortable times for John Wayne fans. The “Duke”, as he was nicknamed, came to define the western genre. From John Ford’s Stagecoach, The Quiet Man, The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance to Howard Hawks’ Red River and Rio Bravo, and Henry Hathaway’s True Grit, Wayne appeared in multiple cast-iron classics. However, in the era of Black Lives Matter, many find his political views repellent. No one has forgotten the interview he gave to Playboy in 1971 in which, using homophobic language, he advocated white supremacy.

The backlash against Wayne is well under way. There were calls last summer for John Wayne airport in Orange County, California, to be renamed. Meanwhile, an exhibition dedicated to him at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts was taken down in July amid a heated discussion about “systemic racism in our cultural institutions”.

Film lovers are therefore having to wrestle with the John Wayne paradox: one of Hollywood’s most beloved stars is also a symbol of much that is toxic about white America.

The debate about Wayne will come into focus again with the release next month of Paul Greengrass’s majestic new western News of the World, starring Tom Hanks. The film (which in spite of its title has nothing whatsoever to do with phone hacking scandals) is clearly partly inspired by The Searchers, one of Wayne’s most famous movies. It is set in the same period, a few years after the Civil War. As in John Ford’s film, the main character is a former Confederate soldier who has an obsessive interest in a young white girl who has been captured and raised by Native Americans. Like The Searchers, it is filled with beautiful, awe-inspiring landscapes.

In a recent interview with Below the Line News, Greengrass described News of the World as “The Searchers in reverse in a funny way. The Searchers is the journey out to find the girl. This is the journey to take the girl home, so it’s sort of the reverse, and that felt very timely for today.”

The British writer-director, who adapted the film from Paulette Jiles’s 2016 novel, has strained out many of the elements that make The Searchers so problematic to contemporary audiences. Instead of Ethan Edwards, the embittered and openly racist loner played by John Wayne in Ford’s western, the film offers us Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, yet another variation on the kindly American everyman so often portrayed by Hanks. He’s not a gun slinging mercenary but makes his living by reading newspapers aloud in frontier towns. There is no escaping the fact that he fought on the side of the army trying to uphold slavery in the Southern states in the war, but in his new life he rejects violence unless it is absolutely necessary.

In The Searchers, Wayne is disgusted that his niece (Natalie Wood), who fell into the clutches of the Comanches, has gone “native”. For most of the movie, we are sure he wants to kill her. Hanks, by contrast, will do anything to protect the orphaned girl (Helena Zengel), recently “rescued” from the Kiowa tribe.

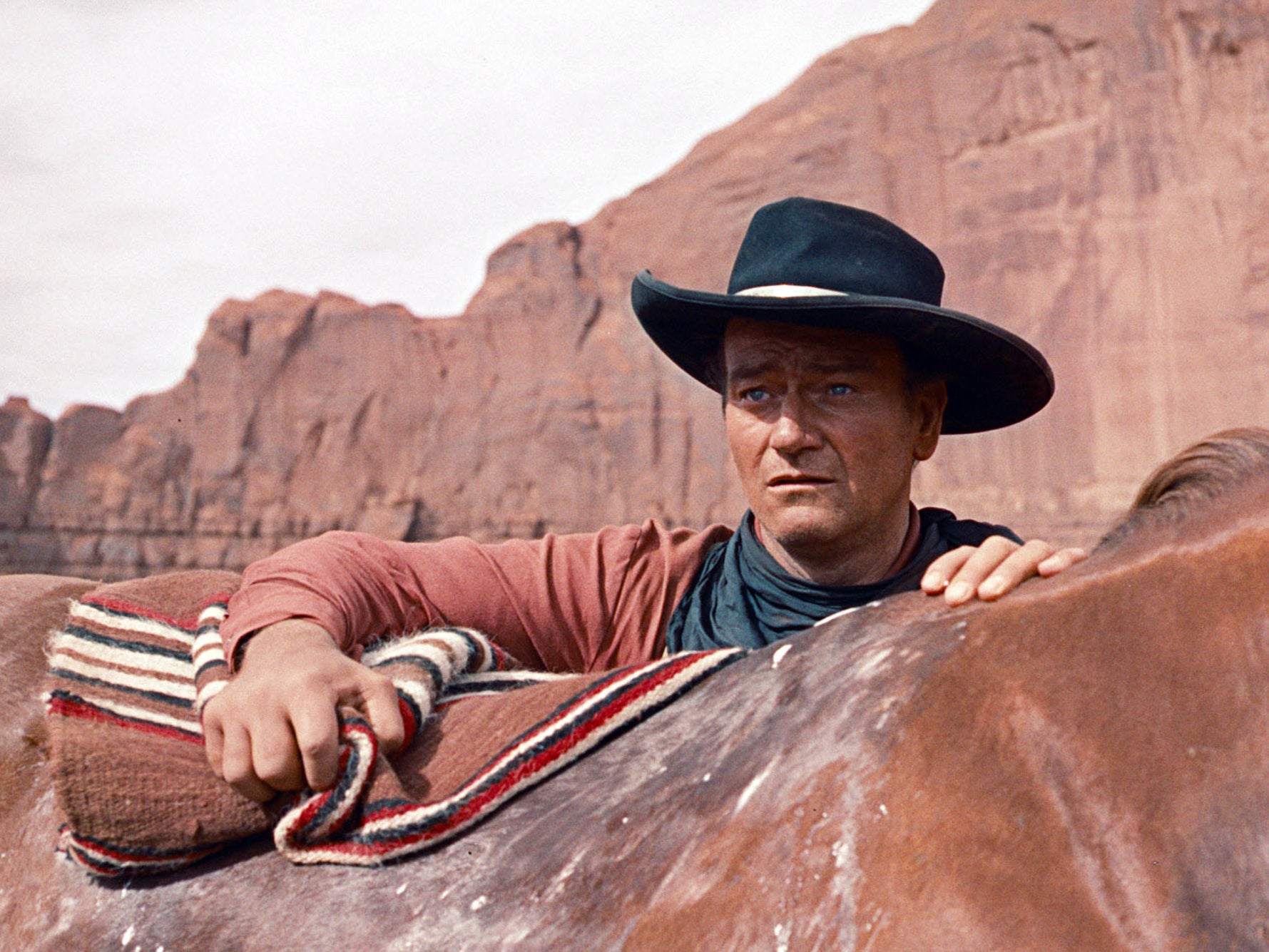

The Searchers is a reminder of Wayne’s power on screen. It’s the darkest role he ever played. In one notorious scene, Ethan shoots out the eyes of a dead warrior, seemingly a pointless and malevolent gesture. “Ain’t got no eyes, he can’t enter the spirit land – has to wander forever between the winds,” he says. He is obsessed with revenge and spends over five years hunting down Scar (Henry Brandon), the Comanche chief who massacred his brother’s family.

Certain scenes in The Searchers are wantonly cruel. Late on, we see the defenceless Comanche women and young children scurrying for cover when the Texas Rangers attack their camp. The Rangers show them no pity at all. In a way, this is a film without heroes. Ethan and Scar provide a twisted reflection of one another. You can’t believe that even a cussed old filmmaker like Ford fully endorses Ethan’s brutality and Old Testament attitudes or his inveterate sexism. Much of the violence happens off screen. Ford relies on Wayne’s brooding, granitic expression to convey the horror. Ethan is the only one who sees the mutilated corpses of the murdered women. He won’t describe what he has witnessed. We read the atrocity in his face.

In News of the World, there are no scenes of Tom Hanks massacring Kiowa people or trying to consign their souls to hell by shooting out their eyes. To have cowboys or soldiers slaughtering Native Americans simply wouldn’t be acceptable in a contemporary western. Instead, the gun battles are between Hanks and marauding ex-army low-lives who first try to buy and then to kidnap the girl. The Native Americans are referred to but hardly seen at all. It’s unthinkable that Greengrass or any other director today would follow Ford’s example and cast a white actor like the German-born Henry Brandon as a Comanche chief.

Greengrass has made a fine film that is bound to get Tom Hanks and his precocious young co-star Zengel considerable Oscar buzz. Nonetheless, it can’t deliver the catharsis that The Searchers eventually provides. It’s a sanitised vision of the west in which the neuroses, traumas and prejudices of the main characters are all muted. It lacks any moment as seismic as the scene late on in The Searchers in which we think Ethan is about to shoot his niece but, instead, takes her in his arms and tells her: “Let’s go home Debbie.”

That scene brought even jaded French cinephiles like director and critic Jean-Luc Godard close to tears. Its power lies in its unexpectedness. Contradicting his own behaviour throughout the rest of the movie, at the moment you least expect it, Wayne suddenly shows grace and tenderness.

There was a preconception that after Wayne became a big star, he gave more or less the same performance in every role. He’d speak his lines in that familiar gruff, laconic drawl. “I… just sell sincerity. And I’ve been selling the hell out of it ever since I got going,” he once said of his technique. Audiences liked to take him for granted. However, his collaborators testified to how hard he worked on the films that mattered to him.

“I never knew the big son of a b**** could act!” Howard Hawks famously said of Wayne after directing him in Red River (1948). Wayne co-starred opposite the brilliant, febrile young Montgomery Clift and easily held his own.

“When I looked up at him [Wayne] in rehearsal, it was into the meanest, coldest eyes I had ever seen,” his co-star Harry Carey Jr later remembered how Wayne stayed in character throughout the shooting of The Searchers. “He was even Ethan at dinner time… Ethan was always in his eyes.”

The older and meaner the character, the better Wayne tended to be, whether in films as sombre as The Searchers or in more laidback affairs like Rio Bravo and Hatari.

Those who loathed Wayne’s politics were invariably disarmed by his affable and gracious behaviour. Bronx-born director Mark Rydell was very wary about working with Wayne on The Cowboys (1972). Rydell was used to method actors. He stood up to the star, refusing to allow him to choose his own wardrobe or call the shots. He even had the gall to kill off Wayne’s character two thirds of the way through the movie. “He (Wayne) at first bristled, but soon embraced the challenge and tried to show that he was as good as any of us. Wayne did instinctively what Actors Studio people learn as a craft,” Rydell commented.

Of course, none of this makes any difference when it comes to the racism and homophobia Wayne betrayed in his now-notorious Playboy interview. To many, he’s just another old monument that deserves to be pulled down. Nobody is going to be naming new airports after him. His legend seems irrevocably tarnished. However, so do those of many other leading figures in politics, the arts and sciences.

It’s instructive to listen to Sam Pollard, the Black American filmmaker whose brilliant new documentary MLK/FBI (about how the FBI snooped into very unsavoury parts of Martin Luther King’s private life) is released this week. When he was a kid, Pollard loved John Wayne. Then, he discovered Wayne’s “horrific” right-wing, anti-communist politics.

“I could have said to myself I am never going to watch a John Wayne movie again, which some people did… but there’s a part of me, the little boy in me, that says, ‘OK, he wasn’t the righteous good guy in real life but I can still watch those movies,’” Pollard reflected. “It’s complex. Do you disown all your heroes and heroines? Sometimes you do. Sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you look at it in a more nuanced way.”

It’s up to the rest of us whether we want to revisit Wayne’s movies or ignore them, but his legacy endures. His best known work remains in easy circulation. At the end of the Trump era, he has become a more polarising figure than ever, adored and loathed in equal measure. You can feel that ambivalence in News of the World. Greengrass’s new western plays both as a heartfelt tribute to The Searchers and as a determined attempt to wipe away its (and Wayne’s) most malignant excesses.

News of the World is out on Netflix next month. MLK/FBI is released this week

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments