The French Connection at 50: Why audiences root for Popeye Doyle against all odds

Half a century after William Friedkin’s revolutionary action film, Geoffrey Macnab looks at how the rogue cop at its centre manages to be so perversely sympathetic

It’s the dead of winter. As Santa Claus rings his bells on a pavement in Brooklyn, a hot dog vendor wanders into a bar. That’s when the commotion begins. A drug dealer with a knife bursts out of the door. Santa and the vendor both try to stop him but he scarpers. They chase him down the street, eventually catch him on a patch of wasteland and gleefully beat him up.

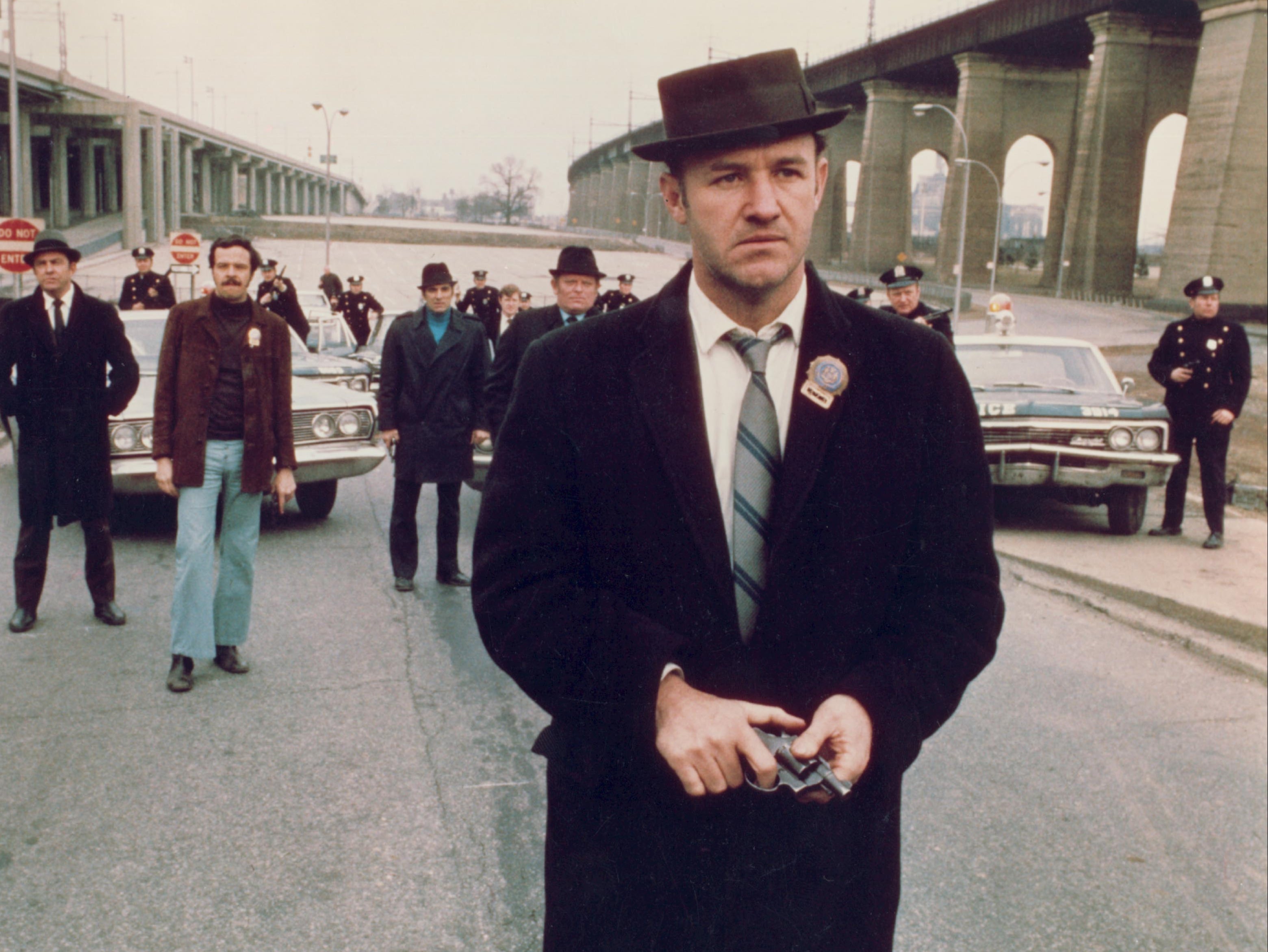

This is how we encounter Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. He may be dressed as Father Christmas but he is an undercover cop with a volcanic temper. The fast food seller is his detective partner, Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider).

Movie protagonists rarely seem so obnoxious at first sight. Popeye is violent, impulsive, possibly racist and doesn’t care at all for the kids he is pretending to entertain. He’s a pug-faced curmudgeon with an alcohol problem and he is a bad Santa to boot. It is not even clear he is an effective cop. He works on intuition but his “brilliant hunches” continually backfire.

Hackman found the character so repellent that (according to biographer Michael Munn) he briefly threatened to quit the movie. It didn’t help Hackman’s mood that director Friedkin shot multiple takes showing the drug dealer (Alan Weeks) being beaten up. “I felt horrible,” Hackman later said, remembering when he repeatedly punched his co-star. Weeks reportedly took the blows (which were very real) in good heart, smiled through them and told Hackman to carry on hitting him.

Half a century ago, when The French Connection was first released, it was considered revolutionary precisely because it was so old fashioned. This wasn’t a counter-culture drama with psychedelic references like Easy Rider (1969) and Head (1968). Nor was it was one of those movies about outsiders chafing against mainstream society like Five Easy Pieces (1970) and Midnight Cowboy (1969). It was a hard-boiled cop thriller shot in dirty realist fashion. There were no mind-bending special effects. The film’s main visual highlights are chases, either in cars or on the subway. Hackman’s rough-hewn quality was perfect for the mood Friedkin was setting. Cinematographer Owen Roizman used natural light wherever possible but, other than in the French-set scenes, there is not a peep of sunshine. Everything is deliberately grey. The streets are strewn with rubbish and graffiti. The famous final set-piece takes place in a derelict old industrial building, with leaking roofs and rubble as a backdrop.

Steve McQueen had been the producer’s first choice as the lead star, but he turned The French Connection down on the grounds it was too close to Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968) in which he had appeared a couple of years before. McQueen might have made an excellent Popeye but he was among the coolest, best-looking actors of his era. Hackman, by his own admission, was far from handsome.

It’s strange, though, the way that cinemagoers’ sympathies work. From the first moment they see him, almost everybody roots for Popeye. Hackman plays him with a long-suffering stoical dignity that verges on the comic. It’s as if he expects the worst. If he goes drinking, he’ll wake up with a hangover. When someone starts shooting at him or a girlfriend chains him to the bed after sex or Fernando Rey’s dapper French villain gives him the slip yet again, he’ll always react in the same fatalistic, hangdog way. His porkpie hat gives him a cartoonish quality. Somehow, against considerable odds, the rogue cop comes across as perversely sympathetic.

The film is based on the true story of two celebrated New York cops, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, who, in 1961, had made a spectacular drugs bust. Both have roles in the film. It’s instructive to watch old interviews with the duo. As they wax nostalgic about the good old days of the 1960s when they could freely arrest, bully and harass anyone they wanted, without having to go to the inconvenience of reading suspects their rights, they look and sound exactly like Hollywood’s favoured version of big city detectives. They’re tough, charismatic and reactionary. You could put them in an episode of The Wire or in an old Sidney Lumet film about police corruption and they would fit perfectly.

Friedkin is quoted in Easy Riders Raging Bulls (Peter Biskind’s book about Hollywood in the 1970s) as having been inspired to make The French Connection by a remark from legendary filmmaker Howard Hawks. “People don’t want stories about somebody’s problems or any of that psychological s***. What they want is action stories. Every time I made a film like that, with a lotta good guys against bad guys, it had a lotta success,” Hawks told Friedkin. This was a moment of epiphany for the younger director. Friedkin wanted The French Connection to be a film his uncle, who worked in a delicatessen in Chicago, could understand. Boiled down to its essence, this is a story about French crooks planning to sell heroin in New York and the cops trying to stop them. It’s full of chases: Popeye Doyle pursuing Fernando Rey on the subway or, most famously, Doyle driving at breakneck speed beneath the Elevated Railway as the train carrying a hitman whizzes by above him.

Friedkin shot the chases in the same naturalistic way as everything else in the movie. “We ran at 90 miles an hour through 26 blocks of big-city traffic,” the director told Sight and Sound magazine, explaining how he managed to make Popeye’s race against the train seem so judderingly authentic. Friedkin himself sat in the back of the car with a handheld camera as the stunt driver, Bill Hickman, sped recklessly through the city, often driving in the wrong lane. This footage hasn’t dated in the slightest. Nor will it ever lose its edge. This isn’t CGI. All those crashes, bumps and screeches happened for real. The virtuoso editing helped too, the rhythmic way that Friedkin cuts between Hackman in the car and the hitman (Marcel Bozzuffi) on the train, terrorising the drivers and the passengers.

If The French Connection had consisted of nothing other than action scenes and stunts, it wouldn’t have amounted to much more than a live action episode of a kids’ cartoon like Wacky Races. The reason it won five Oscars and is still so cherished today is that it had soul and grit as well as speed. During the Seventies in Hollywood, there was a huge gulf between the new style of experimental, European-influenced movies being made by the likes of Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda and the traditional US studio productions. The French Connection was one of the few films that reconciled the opposing ways of storytelling. On the one hand, it was radical and new in its use of jazz, hand-held camera and its hyper-realist approach. On the other, it was in the tradition of all those old James Cagney gangster movies.

Hackman may not have been as good looking as Warren Beatty or Paul Newman but he had a screen presence which matched that of actors like Cagney and Paul Muni in 1930s and 1940s Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh crime thrillers. Friedkin cast several real-life cops alongside him. Most of the actors playing the drug pushers and arrogant French criminals have only limited screen time and very little dialogue but their characters still register strongly. Scheider (later to be seen in Jaws and All That Jazz) excels as Popeye’s sidekick and straight man. He is as calm and pragmatic as his partner is headstrong and impulsive.

Friedkin refused to soften Popeye’s edges. The cop behaves atrociously throughout the film, beating up suspects, arguing with superiors, getting drunk, lusting over female cyclists, stealing cars and putting his colleagues’ lives at risk. Nonetheless, Hackman gives him a soulful quality and just a hint of vulnerability. It’s a warts and all performance that seems infinitely richer than those of sleeker, more conventional leading men. For Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, being a New York detective isn’t just a job but a sacred cause. Fifty years on, you can’t help but admire the manic seriousness and passion with which he goes out on the beat.

The French Connection, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, is available through Amazon Prime Video

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments