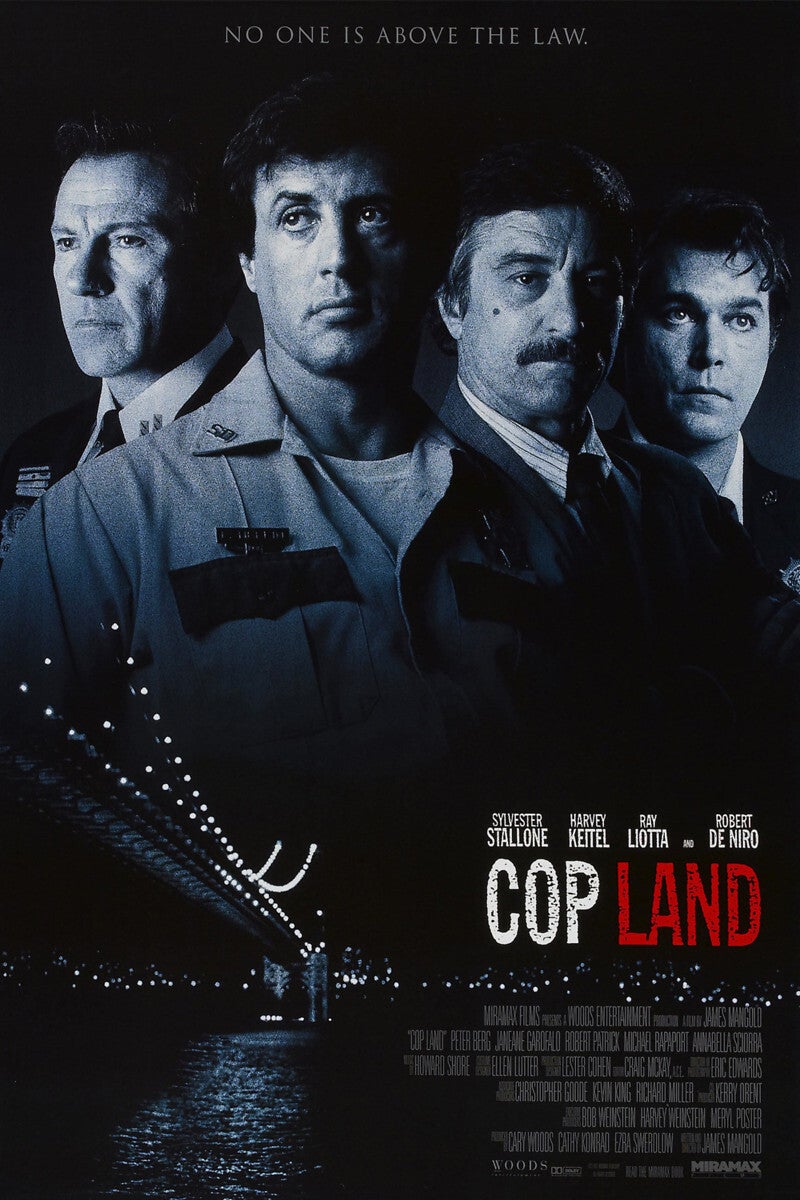

Cop Land at 25: It had all the ingredients to be a modern-day classic – what went wrong?

James Mangold’s 1997 New Jersey-set police thriller starring Sylvester Stallone, Harvey Keitel, Ray Liotta and Robert De Niro was supposed to be the new ‘Goodfellas’ but, as its director-writer tells Geoffrey Macnab, it was beset by problems caused by its executive producer, Harvey Weinstein

Fucking rat,” veteran NYPD cop Ray Donlan (Harvey Keitel) sneers at the retreating back of internal affairs officer Moe Tilden (Robert De Niro) early on in writer-director James Mangold’s Cop Land (1997). Their brief encounter in a coffee shop is an electric moment – the first time Keitel and De Niro had shared the screen with such ferocity in a thriller since they were the young stars of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976).

They may have been friends, but that didn’t stop them from competing in front of the camera. Both were trying to steal the scene from under their rival’s nose. De Niro’s Moe fiddles with the sugar for his coffee while Keitel’s Ray reminisces about when they were classmates at the police academy. For all their seeming bonhomie, they clearly loathe each other. Moe represents the rule of law. Ray is the quintessential crooked cop, as corrupt as they come; a cynical old-timer pulling the strings in the fictional town of Garrison, a sleepy, suburban community just a few miles across the George Washington Bridge from New York. Half the residents in the town are serving police officers.

In the wake of the George Floyd murder, the movie seems more topical than ever. Its plot hinges on Moe’s investigations into the killing of two Black teenagers by a hothead young white cop. It was inspired by Mangold’s own experiences growing up in Washingtonville, a town just like the fictional Garrison across the river from New York.

“The community I grew up in was a result of what is called ‘white flight’ from New York in the 1970s,” Mangold explains. This was an era when the Big Apple seemed to be rotten at the core, decaying with debt, violence and police brutality. “A lot of young men, cops, firemen, other civil servants, got out,” Mangold remembers. They still worked in New York but lived outside the city.”

Mangold, speaking to me in a break from post-production on the new, as yet untitled Indiana Jones movie, was a half-Jewish, half-Christian kid. His parents were artists with very liberal values. “[But] I was growing up in a town that was the definition of Reagan conservative [beliefs], very suspicious of the welfare state. While I would not say that they [the cops living in the town] all were racist, they were very wounded emotionally by what they felt was the futility of their jobs,” Mangold reflects.

The cops likened themselves to “garbage men”, arresting the same people again and again. “The communities that most of the cops in my town had grown up in – Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx – were now entirely ethnic communities, no longer white enclaves. There was a time when the Bronx and Queens were completely white enclaves, Italian and Irish – and now they were not.”

That’s why so many were keen to move their families outside New York. Their prejudices fed into the attitudes of their own children – Mangold’s classmates – who had an equally distrustful and “cynical view of other ethnicities”.

In this period, Mangold believes, being a cop in New York was like being “a 9-to-5 Vietnam [war] soldier”. “The cops led this incredibly cruel life, which was to cross the bridge and descend into the insanity of what was the streets of New York at that time. The war on drugs was at its height. The Aids crisis was at its height. The crack crisis was at its height. That produced a kind of darkness. It [New York] was their war zone, but they came home and they had an enclave that was free from those anxieties.”

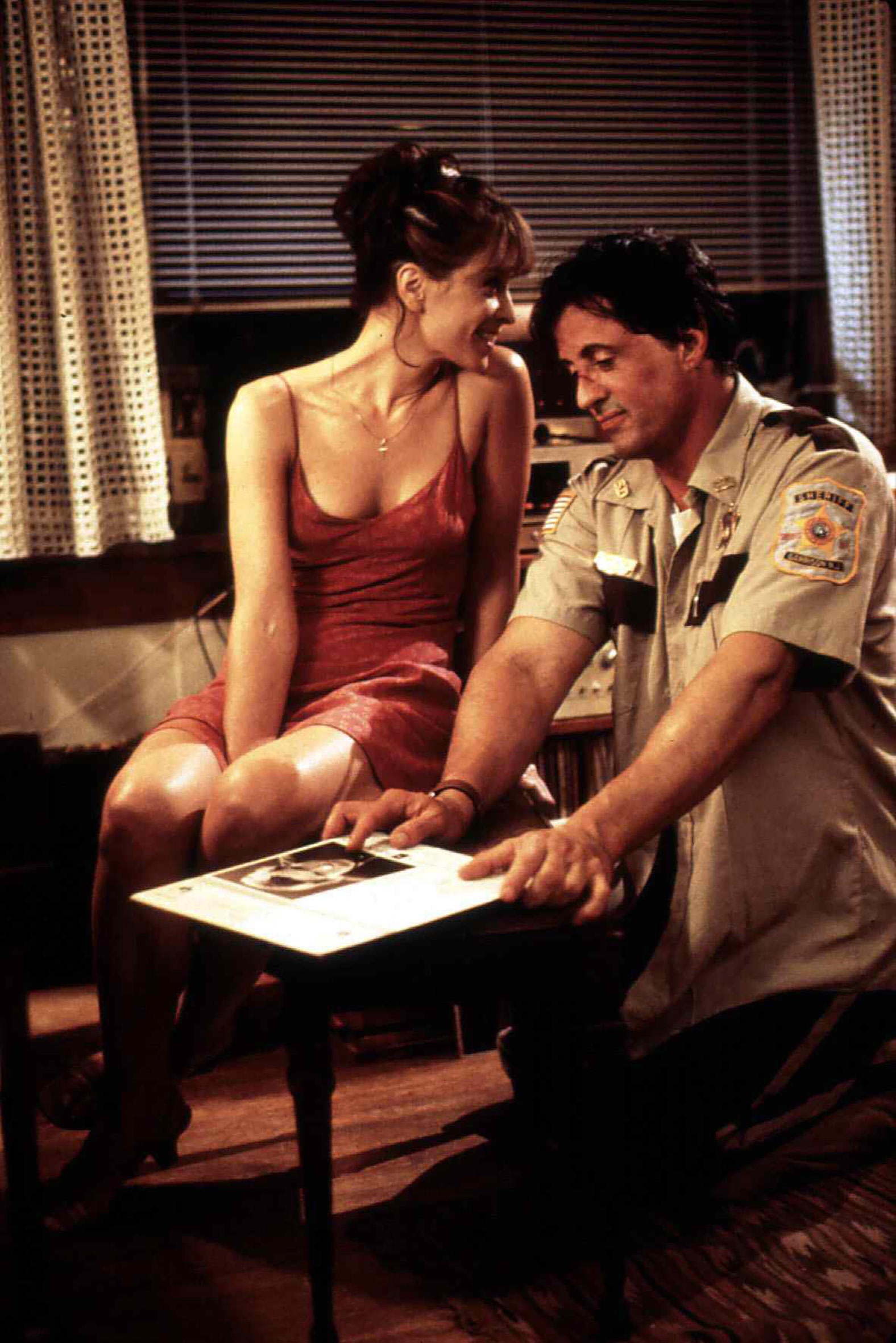

In the film, Garrison already has its own law enforcement in the shape of local sheriff Freddy Heflin (Sylvester Stallone), but he is a lumbering, slow-witted figure. Deaf in one ear, he spends his days investigating minor traffic violations and his evenings playing pinball. His best friend is Gary Figgis (Ray Liotta), a cocaine-addicted cop who, in another memorable early scene, sticks a dart up the nose of a rogue officer taunting him in a bar.

Mangold is probing away at racism and graft within the New York police department. He throws in the visual flourishes and the kind of colourful, hard-boiled characterisation and dialogue found a few years earlier in Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990). Whereas Scorsese was showing the inner workings of the New York mafia, Mangold was holding the city’s police force up to the microscope. Each organisation seems like a twisted reflection of the other. Just like the gangsters, the NYPD officers live by their own code of “omertà”.

Cop Land had all the ingredients to be a modern-day classic. Liotta, who died suddenly last month aged 67, gives one of his best performances outside Goodfellas as the self-centred but conscience-stricken Figgis, full of remorse about his part in Donlan’s machinations. Keitel is equally good as the amoral, Iago-like villain, doggedly loyal to his fellow cops but ready to murder his own kin to protect his criminal network. Stallone, for once, escapes his familiar action-hero stereotype. A moustached De Niro brings smirking intensity to his role as the internal affairs officer.

During pre-production, De Niro had taken Mangold – then a young director making only his second feature – under his wing. “Bob went out of his way in prep for the film to extend the invitation of spending a lot of time working on the script, hanging out. He introduced me to Harvey [Keitel], who lived in the same building at that time.”

The veteran star didn’t work often with young directors because they would become too intimidated by him. “His solution to that was to befriend me and have me over for tea, and we went off on little scouting trips to do research. It was a huge gift to me. It taught me not to be afraid of great actors but to embrace them, take them in. If an actor like Bob wants that kind of interaction, I assumed everyone did. It gave me permission to not be shy about asking for what I think I need from actors. When you have all these very strong personalities with huge reputations, they still need you to be the boss and make the decision.”

The chemistry between the young director and his stars is obvious. Why, then, isn’t Cop Land more highly valued by critics and fans?

If the film has a memorable on-screen villain in Keitel, it had an even more formidable and damaging one behind the scenes in the shape of its executive producer, Miramax boss Harvey Weinstein, who meddled in everything, from the casting to the editing, and even tried to rewrite the ending.

Weinstein’s dark shadow continues to loom over the movie. Its co-star Annabella Sciorra, who plays a battered wife married to one of the film’s many rogue cops, was one of the main witnesses alleging sexual assault against the disgraced producer during the 2020 trial that led to his conviction and imprisonment.

Mangold is utterly withering about the “Machiavellian” behaviour of Weinstein, his brother Bob and other colleagues at Miramax.

“Certainly, Harvey was much more fearsome than anything I’ve ever seen before or since in terms of the implicit bullying. There was always this threat of violence in the air around them. The kind of mood and tension of Cop Land was not unlike the tension at Miramax. It was a kind of mob-rule company.”

The director insists that, in spite of its indie credentials, “Miramax was always about money”.

“They played to certain constituencies that would give them a core audience but it was always as cynical as a Hollywood studio would be, just playing to a different audience. But what was unique at Miramax was the outsized personalities, egos and aggressions of the guys who ran the studio. And, yes, it was a trial by fire.”

Mangold describes the “most painful” part of the process as being the post-production. “I had literally both Weinstein brothers in my cutting room, sitting there for three or four hours a day in a room…, pacing about, suggesting ridiculous cuts,” Mangold sighs at what clearly remains a painful memory.

Miramax had been hoping that Cop Land would do for Stallone what the company’s earlier film, Pulp Fiction (1994), had done for John Travolta. It would encourage audiences to see him in a new light, not as Rambo or Rocky but as a character actor playing a vulnerable, damaged man. Stallone [reluctantly] put on weight for the role.

“He took some pushing to gain the weight. Even up till two weeks before we started, he had barely put on seven extra pounds. He looked like Adonis,” Mangold remembers of Stallone, who eventually bulked up by going on a crash diet of peanut butter.

The whole point of the film is that Stallone’s character is an ordinary man discovering his own integrity and inner courage. Harvey Weinstein, though, wrote a saccharine new ending for the film that portrayed Stallone in a more conventionally heroic light, being accepted into the NYPD from his hospital bed by the De Niro character. A Miramax exec warned Mangold about what Weinstein had done. The exec advised Mangold not to dismiss the new ending out of hand. “So Harvey calls. He reads me the pages of this scene… first of all, the movie is so dark that I didn’t think the audience was going to take a cherry on the end. It was horribly written and I didn’t know what to do.”

Eventually, Mangold contacted De Niro and explained the situation. “Bob was like, ‘I am not doing that’.” Mangold explained that Weinstein would pay him a fortune to do the scene. “I don’t care what he pays me. I am not doing that scene.” Weinstein had to defer to De Niro and his ending wasn’t shot.

Mangold has gone on to direct such hits as The Wolverine (2013), Logan (2017), Ford v Ferrari (2019), the Oscar-winning Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line (2005), the western remake 3:10 to Yuma (2007) and the Tom Cruise action comedy Knight and Day (2010). He has worked successfully both inside the studio system and independently while tackling many different genres. Nonetheless, Cop Land remains a very raw subject for him. It’s a source both of huge pride and of considerable frustration. This was intended as a very sombre and violent movie. Almost all its main protagonists end up dead. It was a long way removed from the pop-culture high jinks of a Quentin Tarantino movie, yet Miramax still had absurdly high expectations that the film couldn’t possibly reach.

“Inevitably, I felt like I had failed. That still hangs with me... I am very proud of the movie but you can never unring a bell. I can never forget what I went through making it,” Mangold’s voice tails off. The consolation, though, is that the film is “still being talked about” while so many other movies from the Weinsteins’ reign of terror have vanished without a trace.

‘Cop Land’ is available on Amazon Prime. James Mangold’s untitled fifth Indiana Jones film is due to be released next summer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments