Books of the month: From Donal Ryan’s The Queen of Dirt Island to Audrey Schulman’s The Dolphin House

Martin Chilton reviews six of August’s biggest new books for our monthly column

The music business is full of the ghastliest people,” insists Richard Fairbrass, who, along with brother Fred, gained worldwide fame with the catchy 1991 hit “I’m Too Sexy”. Their unusual memoir Still Too Sexy: Surviving Right Said Fred (Omnibus Press) is a 230-page joint interview, edited by Joel McIver, and it is salacious, candid, funny and shocking. The book captures the anarchy of sudden celebrity. It seems that one of the many dubious perks of fame is being sent a weird video of a fan having his scrotum nailed to a wooden bench. Among the entertaining stories that the siblings swap are those about stomach liposuction, making the Queen giggle, blowing a chance to be in Die Hard 2, and Ned Sherrin’s predatory behaviour. Of the ‘suck and f***’ swingers’ parties for celebrities to which they were invited, Fred remarks drolly that “it was very Eyes Wide Shut”. One anecdote proved too risky to tell in full, though. It was the time they saw “a supposedly straight male pop star sucking off a well-known footballer” when the lift doors of a luxury hotel in Birmingham suddenly opened. “If we revealed who either of them were, we’d get killed,” says Fred.

Right Said Fred’s tell-all autobiography is just one delight among a tasty smorgasbord of non-fiction out in August. In Floor Sample: A Creative Memoir (Souvenir Press), best-selling author Julia Cameron deals, in part, with her failed marriage to director Martin Scorsese, during the Taxi Driver era. “Coked up and drunk, I was a handful,” admits Cameron. She spent a lot of time in Malibu with musicians and their partners, when her husband was making The Last Waltz with Robbie Robertson and The Band. Life there gave her “a comforting feeling of normalcy”, she notes, deadpan, because “drug habits were common among rock-and-roll wives”.

Tempestuous marriages come into Norwegian anthropologist Erika Fatland’s enchanting book High: A Journey Across the Himalayas Through Pakistan, India, Bhutan, Nepal and China (Maclehose Press, translated by Kari Dickson). Fatland spent eight months in the Himalayas researching her book where she talked to a Mosuo woman about the loose arrangements of “walking marriages” – relationships that amount to little more than a man visiting his wife at night and leaving early the next morning. “It’s very easy to get divorced,” Sadama tells the author: “He can either stop coming or she can lock the door”. Incidentally, Fatland also chatted to some old men who claim to have seen yetis. It appears they are twice the size of yaks and really do have hairy feet and hands.

Jane Stanford, the co-founder of one of America’s most prestigious educational establishments, was murdered in 1905. In Who Killed Jane Stanford? A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits and the Birth of a University (WW Norton & Company), historian Richard White pieces together a bizarre tale of spiritualism, police corruption, cover-ups, missing evidence and social hypocrisy. It’s an engrossing real-life whodunnit mystery.

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones’s A Question of Standing: The History of the CIA (Oxford University Press) uncovers the dirty tricks of the Central Intelligence Agency after its founding 75 years ago. The account carries through to the Donald Trump era, which marked a “low point in White House-CIA relations”. The well-researched publication also has salient points to make about President Obama’s overuse of drone strikes, and how books were cooked to cover the “absurdly low” casualty figures of innocent people who were killed because of inaccurate strikes and false intelligence.

Tansy E Hoskins’s The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion (Pluto Press) has a foreword by Andreja Pejić, reflecting on the “dirty and degrading work” involved in modelling. The fashion industry is now worth an estimated $2.5 trillion a year, and Hoskins examines a multitude of putrid problems, including the theft of models’ wages, damaging body image issues for teenagers, endemic sexual violence, gender-based brutality at garment factories, racism, the exploitation of third-world workers and attacks on labour movements. Fashion businesses don’t only exploit women – they also ravage the planet and animal life. You will need a particularly thick skin to avoid wincing at the account of how crocodiles are kept in squalid captivity and then killed in horrendous ways for their hides.

Another month, another comedian’s novel. Kevin Bridges kept himself occupied in lockdown writing The Black Dog. My fiction recommendations fall elsewhere, however, and among my pick this month is Barney Norris’s Undercurrent (Doubleday), a deft novel about a struggling thirtysomething man’s chance meeting with a girl he once saved from drowning and the changes the event sets in motion. In The Lost Diary of Samuel Pepys: a novel (Moonflower Books), Jack Jewers conjures up a zestful imagining of the lost late memoirs of one of Britain’s great historical chroniclers. Joanna Campbell’s Instructions for the Working Day (Fairlight Books), a clever reflection on ramifications of the Stasi era in East Germany, is an elegant, chilling reminder of what happens when people set out to deliberately disintegrate another person’s spirit. Jim Crace brings his usual elegance to Eden (Picador), a beautiful fable set after the fall of Adam and Eve.

Finally, I thoroughly enjoyed Caroline Greene’s sparkling novella Lessons at the Water’s Edge (Adhoc Fiction). Greene, whose tale won the 2022 Bath Flash Fiction Novella-in-Flash Award, tells the enchanting story of a young woman leaving problems at home to live in a different country and teach English to two young Italian girls. It is as much a love letter to language as a tale of how people mould and connect us.

Memoirs by Martyn Ware and Jean Fullerton, a history book by Philip Parker and novels by Jess Kidd, Donal Ryan and Audrey Schulman are reviewed in full below.

The Night Ship by Jess Kidd ★★★★★

The story of the Batavia is now recognised as one of the worst disasters in maritime history. On its maiden voyage from the Netherlands to the Dutch East Indies, it was shipwrecked off the western coast of Australia. The passengers and crew who survived drowning made it to a small, inhospitable island where mutiny and violence ensued.

The bare bones of this tragedy inspired Jess Kidd’s majestic novel The Night Ship, an enthralling tale of cruelty, friendship and the fates of two children, hundreds of years apart, bound together by the disaster. Kidd, a Costa Award-winning writer, packs the story with superb characters, high emotion and drama, in historic fiction that cleverly interweaves the events of 1629, when a young girl was marooned, with a child in 1989 who finds a home with his grandfather on the same barren Beacon Island.

Although it is clear a great deal of research has gone into the novel – Kidd visited a replica “Batavia” and the novel features real characters such as the sly young steward Jan Pelgrom and the beleaguered kitchen boy Smoert – The Night Ship is never overwhelmed by historical detail. Instead, this gripping story ebbs and bobs with surprises from Kidd’s sparkling imagination.

‘The Night Ship’ by Jess Kidd is published by Canongate on 4 August, £16.99

A Child of the East End: Memories of Love and Life in Cockney London by Jean Fullerton ★★★★☆

Jean Fullerton, who has written 19 historical novels and earned the nickname “The Queen of the East End saga”, certainly had a bumpy upbringing on an estate off London’s Commercial Road. In her funny, stark memoir A Child of the East End: Memories of Love and Life in Cockney London, Fullerton, born in August 1954, recalls that “my mum’s stock reply to any enquiry as to what was for tea would be, ‘sh-t with sugar on’.”

The book pulls back the covers on what it was like being a working-class East End girl in that era, from the way her accent was constantly judged, to the reality of dealing with middle-class authority figures. Doctors, for example, “were habitually rude and bullying”, but were treated with a “god-like reverence”. She recounts a visit to her own physician, who wore a morning coat and a bow tie and “looked as if he’d been around since Queen Victoria’s coronation”.

A Child of the East End offers a powerful corrective to a romanticised, nostalgic way of looking at a past that was, in fact, often regressive and oppressive. She recalls what it was like to be 17 in 1971, “fighting off men who kept offering to give us a lift home or just wanted to take us down an alley and show us something”. If you were assaulted or raped, “the police would have viewed it as your own fault”. Lots of men had misogynistic views about how young women should be chaste: “One of the girls I worked with recounted how she’d put her hands down the front of her fiancé’s trousers and grabbed his erection. Rather than accepting her sexual needs, he’d told her, ‘Get off me, you dirty bitch’.” Fullerton worked for a time as a district nurse and encountered ignorance and social pressures about contraception.

Given the US Supreme Court’s recent backward decision to overturn Roe v Wade, it’s instructive to read Fullerton’s account of the awful conditions for women in the UK before abortion was legalised in 1967, “when women had to take matters into their own hands”. Along with the horror of backstreet abortions, or pregnant girls having to bear children and then be coerced into putting them up for adoption and suffering terrible post-natal depression, there was widespread ignorance facing women forced into trying DIY terminations. Fullerton described “the old favourite” of women entering a blisteringly hot bath after consuming large quantities of gin. For these poor women, “it had no effect other than having a splitting headache and a scalded rear end,” Fullerton recalls.

One of the most grimly fascinating sections is her account of joining the “very male world” of the Metropolitan police, “an eye-opener even for a streetwise East End girl,” she notes. This was 1976 and Fullerton says that Women Police Constables were regarded as too emotional, insufficiently tough and were routinely degraded: “It was common to hear even senior officers allocate a ‘Plonk’ nickname to all WPCs”.

Fondling and smutty talk from male officers was the norm, and occasionally there was sanctioned sexual assault. “The worst thing that happened to some WPCs, thankfully never to me, was being station stamped,” Fullerton recalls. “Usually instigated by one of the older officers, a WPC who they regarded as being a bit stroppy, stuck up or not pulling their weight would be bent over a desk, her skirt pulled up and knickers down before having the rubber stamp with the police station arrest crest pressed on her bare flesh”. Fullerton does well to expose a 1970s world that sometimes stank.

‘A Child of the East End: Memories of Love and Life in Cockney London’ by Jean Fullerton is published by Corvus on 4 August, £8.99

Small Island: 12 Maps That Explain the History of Britain by Philip Parker ★★★☆☆

As the last Ice Age approached, before meltwater separated Britain from Ireland, a wide, low plain still connected Britain to Europe. Britain only became an island after a massive flood around 5500 BC. In Philip Parker’s engrossing book Small Island: 12 Maps That Explain the History of Britain, he uses maps to chart the formation and then break-up of regions under British rule, offering stimulating observations about the cultural evolution of the nation along the way.

Parker provides a richly entertaining canter through Britain’s past and he identifies some common themes – including how foreigners have always provided “a convenient scapegoat for other ills”.

Small Island also takes in Parker’s predictions for the future. In the final map, ‘A Possible future for Britain, 2040’, you can see that Scotland, Wales and Ireland have, by then, left the United Kingdom – and Yorkshire and Cornwall are places “with strong autonomy movements”. Beyond lowering standards with his habitual dishonesty and Covid law-breaking, could laying the seeds for a break-up of the Union turn out to be Boris Johnson’s lasting legacy?

‘Small Island: 12 Maps That Explain the History of Britain’ by Philip Parker is published by Michael Joseph on 4 August, £25

The Dolphin House by Audrey Schulman ★★★★☆

In the mid-1960s, 23-year-old Margaret Howe Lovatt was part of a Nasa-funded project to communicate with dolphins. Soon she was living with ‘Peter’ 24 hours a day, in a house converted into a dolphinarium in the Virgin Islands resort of St Thomas. The experiment went tragically wrong after she admitted to regularly “pleasuring” the dolphin. When Hustler magazine published the revelations, accompanied by a lewd cartoon, the plug was pulled on a ground-breaking trial to teach dolphins human language.

Well into the 21st century, tabloid newspapers continue to sensationalise the story – The Sun referred to Margaret’s “wild 10-week fling” with a dolphin, while the New York Post joked about a dolphin who “turned hot for his teacher” – but Audrey Schulman has taken these strange real events and written a beautifully realised novel about a woman caught in the male scientist world of the 1960s and her struggle to explain empathy, friendship and tolerance.

In the novel Margaret is Cara and Peter is Junior. The Dolphin House is as much about failed masculinity as it is human-dolphin bonding. Schulman has sharp things to say about misogyny and the subjugation of women (“in general, they acted like nervous guests”) by cold and ruthless men keen to muck around with nature.

The Dolphin House is a deeply engrossing read and a psychologically astute study of the way humans, mimicking Cara’s training of dolphins, use rewards and punishments to make each other perform.

‘The Dolphin House’ by Audrey Schulman is published by Europa Editions on 11 August, £12.99

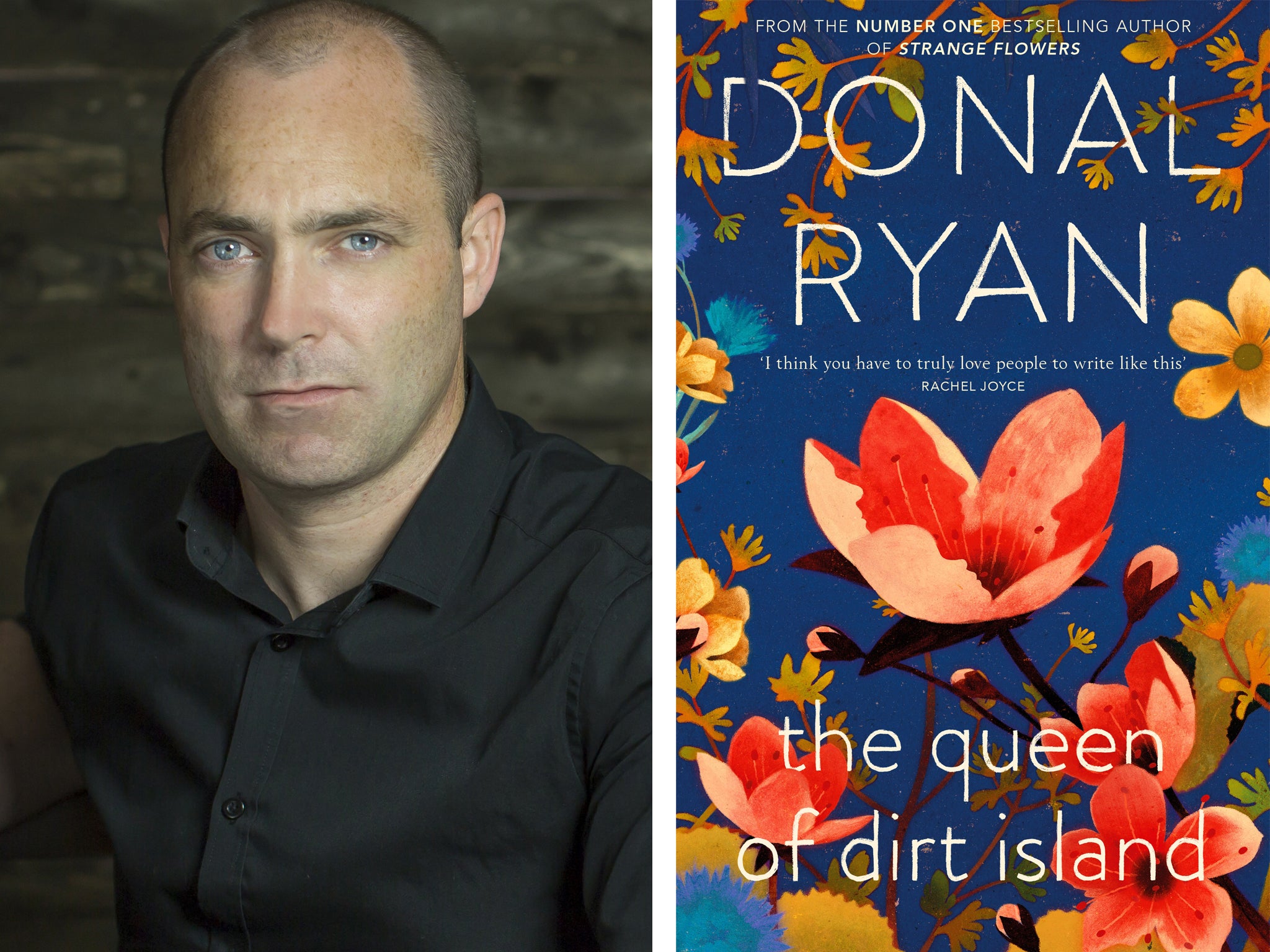

The Queen of Dirt Island by Donal Ryan ★★★★★

When Donal Ryan hits his groove, the writing is simply sumptuous. This is particularly evident in two stunning and poignant successive small chapters, Girls and Boys, in his new novel The Queen of Dirt Island.

This soaring tale of four generations of women in a small Irish town is bursting with humour and pathos. The interactions between the independent-thinking Nana and her daughter are a delight – spiky set-pieces in which they discuss and digest local news, gossip and personalities. They also have a fantastically raw and edgy dynamic. “When Nana complained that the water was too cold or too hot Mother would tell her it was the exact right temperature as it always was, and to shut her face or she’d f***ing drown her, and Nana would shriek with laughter, sitting in her bath seat like a white-haired liver-spotted baby, waiting for her back to be soaped,” narrates Saoirse, the granddaughter whose own unplanned pregnancy changes the household forever.

Saoirse is an incredibly poetic and poignant protagonist. The way Ryan shows her suffering – how the oppressive behaviour of people narrows and closes life into “a tight smallness, a knot of meanness and unfairness” – is intensely moving. Although women are the driving force of the novel, inadequate men stalk this modern Ireland, whether they are frantically peacocking boys or middle-aged men who are still, in Nana’s words, “sucky-babbies”.

Ryan does cruel swearing well – one girl dubbed ‘Bazongas Quirke’ is a “fat f***ing goody-two-shoes” – and Nana’s takedown of a vain, pompous postman is like a devastating stand-up routine. The Queen of Dirt Island contains shocking twists, deaths, reflections on how fiction misappropriates lives and a sharp portrait of how love can lift and twist the human heart; yet it is underpinned by an overriding empathy that is deeply affecting. This is another glorious novel from Ryan.

‘The Queen of Dirt Island’ by Donal Ryan is published by Doubleday on 18 August, £14.99

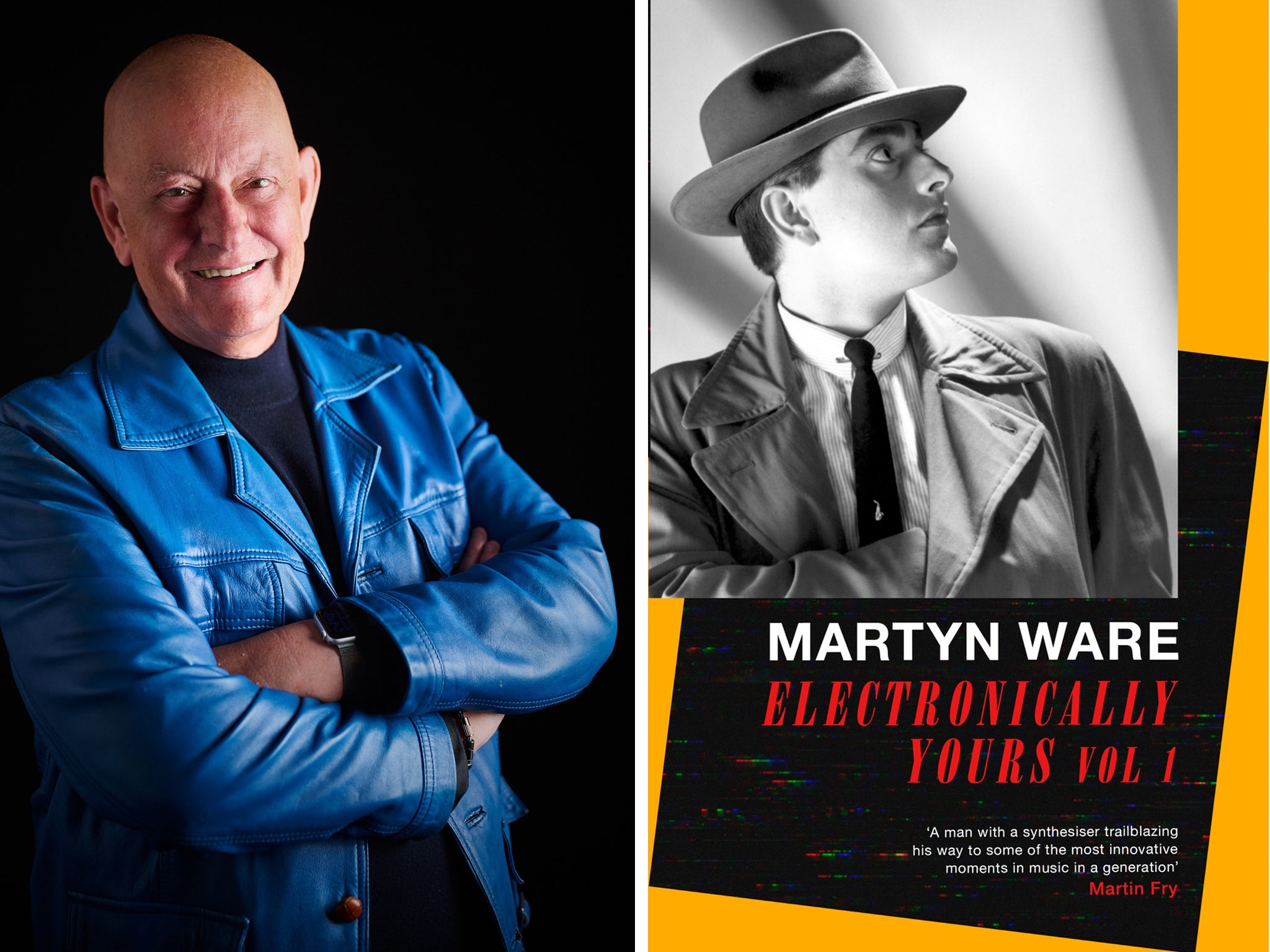

Electronically Yours, Vol 1: My Autobiography by Martyn Ware ★★★☆☆

Since Martyn Ware declares that “I can honestly say that I don’t give a f*** what anyone thinks any more”, he won’t mind me saying that the first volume of his memoirs is an extremely up-and-down affair. Sheffield-born Ware, who was a founding member of hit 1980s bands the Human League and Heaven 17 – as well as being the producer who revitalised Tina Turner’s career in 1983 with “Let’s Stay Together” – covers the period up to 1992 in this autobiography.

On the plus side, there are good yarns from the music industry – including a memorable tale of Iggy Pop’s encounter with Hell’s Angels stories, an account of a drinking escapade while watching Dizzy Gillespie in Paris, anecdotes about the sneakiness of Prince, what is what like dealing with the “arseholes” in charge of Top of the Pops and what happens when you fall-out with ruthless Virgin Records executives – all told with verve.

There is also an overarching Yorkshire bluntness in his verdicts on fellow musicians. Ware dismisses Talking Heads as “just another corporate rock band” and offers a withering assessment of Dire Straits. “I thought, ‘what an appropriate name, f***ing boring – this noodling guitar-based rock was everything I thought needed to be thrown away as the last dying dregs of rock and roll,’” he says after seeing the band in their early days. Socialist Ware also explains why he declined to work with Margaret Thatcher-supporting Rod Stewart, because of his support for a Tory leader who, in Ware’s words, was a “manifestation of middle-class entitlement and evil”.

After an agreeable ramble through his teenage years, Ware deals with the origins of Heaven 17 – a band named after a reference in Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, following the rejection of the name Goggly Gogol – and the messy break-up of the Human League. He’s funny about football and his beloved Sheffield Wednesday, a passion instilled in him by his father, whose hatred of Sheffield United extended to avoiding streaky bacon because “it matched SUFC’s strip of red and white stripes”. I was also warmed by his account of working at a supermarket where he was so bored that he “used to give old-age pensioners free cheese for a laugh”.

The downsides to the book did grate, though. Among them are a reliance on Wikipedia entries, the repeated grandiose references to “you’ll find out more in Volume 2” and the overlong (100 pages) track-by-track guide. Although there are moments of real honesty – he admits to getting a court order for unpaid rent, to drinking and drug-taking and being “self-centred and acclimatised to success” – there is a jarring, oddly creepy story in which he admits to taping singer Terence Trent D’Arby during a recording studio tryst, capturing “the sounds of lovemaking”. A few paragraphs later, Ware attacks The News of the World for invading his privacy in a quest for a front-page scoop. The inherent contradiction does not seem to bother him.

‘Electronically Yours, Vol 1: My Autobiography’ by Martyn Ware is published by Constable on 25 August, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments