The gathering economic storm will break soon – and we are nowhere near ready

Those wishing to bury their heads in the sand in the hopes that the financial crisis awaiting us will blow over should think again, writes James Moore

The UK consumer has repeatedly bailed out the country’s economy when it has looked in danger of hitting the buffers – thanks to their spending power.

As such, a cursory glance at the headline numbers put out today by UK Finance, the banking trade body, could provide some comfort for the “recession might never happen so stop talking Britain down” brigade led by one Liz Truss.

Spending via debit and credit cards came in at £75bn, compared to £72bn in the first three months of the year. Rising prices obviously pushed the number up but it should be noted that the overall volume of transactions also rose. See! The consumer’s going to do the rest of the economy a favour. Even with all that inflation.

House purchases, meanwhile, have recovered to pre-pandemic levels – despite a red-hot market leaving buyers with steam coming out of their ears and tears leaking from their eyes. In its latest update, Halifax revealed that prices, which fell 0.1 per cent month on month in July, returned to growth of 0.4 per cent in August. Although, the year-on-year figure (11.5 per cent) was down a bit (from 11.8 per cent).

Back to the UK Finance numbers. Dig a little deeper into them and it becomes clear that “don’t worry, be happy” (readers of a certain age are now going to be hearing that song in their heads all day) fans of Trussonomics are living in a fool’s paradise. A notable feature here is that borrowing via personal loans increased. These are generally used for larger purchases.

Now, consumer confidence is currently very low. Last month, for example, data company GfK’s regular survey slumped to a new nadir of minus 44, quite an achievement given the upheavals the UK economy has undergone since the series began in 1974.

So why the apparent binge on big-ticket items? It may be because consumers, having taken note of rising inflation, are simply seeking to make major purchases ahead of the price hikes to come. Fridge looking old? Now’s the time to buy a new one. This could have boosted the overall numbers.

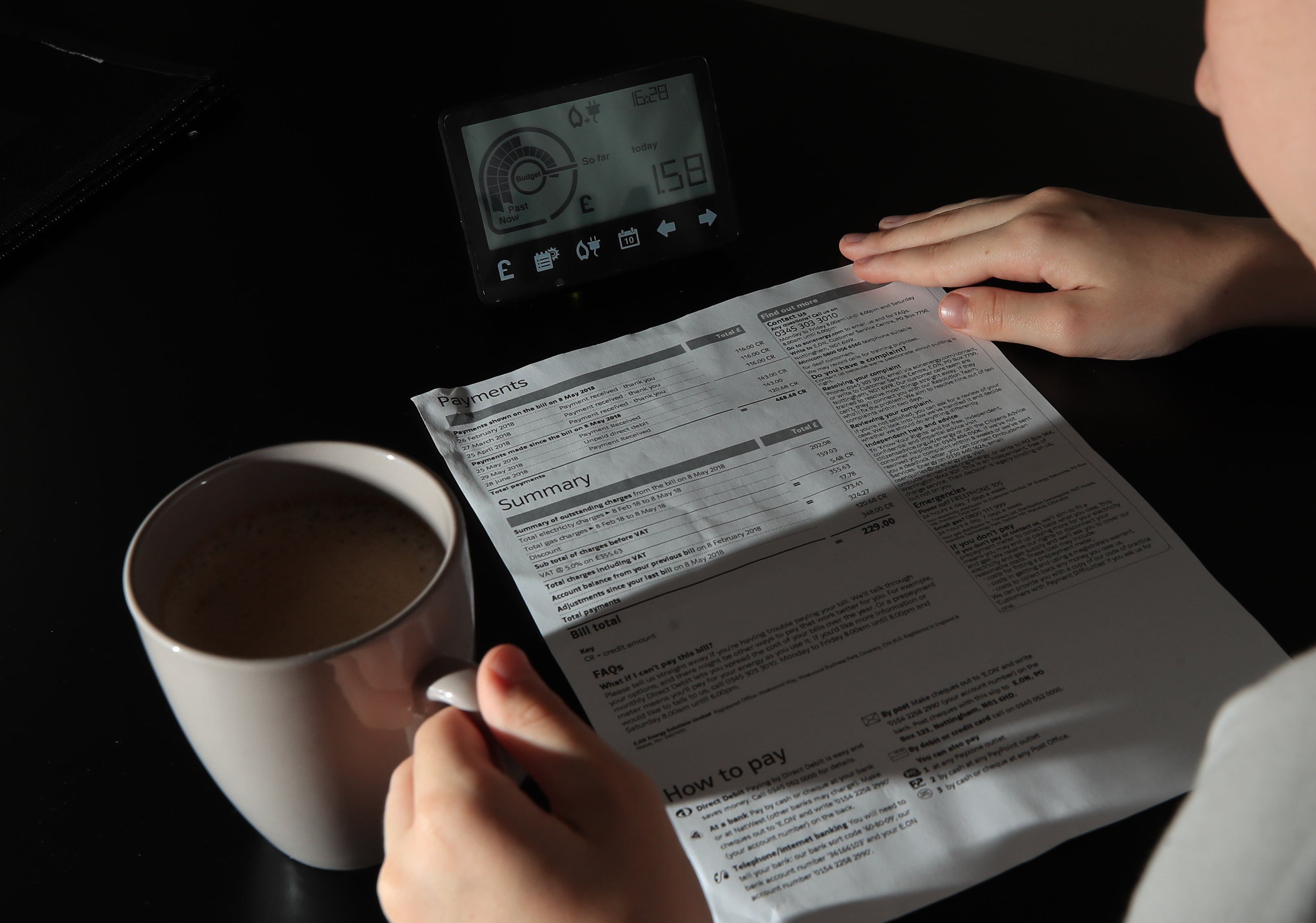

A more obvious sign of consumer stress comes in the form of a rise in overdraft levels (to £5.5bn). The figure is still roughly 5 per cent off the sort of levels seen during the pandemic. But during the peak of Covid-19, millions of people saw their incomes declining through being on furlough, which paid 80 per cent of their salaries up to a maximum of £2,500. So of course their overdrafts were high during lockdown. Household savings, meanwhile, have flatlined. Britons are starting to lose the capacity to put money to one side.

Taken together, the numbers give this release the feel of a gathering storm. When it comes to mortgages, however, that storm has started to break.

Homeowners are in a far more fortunate position than Britain’s poorest. But the less fortunate among them may still find themselves in a nasty jam over the coming months

Consumers on fixed-rate deals are obviously shielded from rising interest rates. But every month, some of those fixes come to an end, requiring the borrower to refinance if they don’t want to get stranded on their lender’s (expensive) standard variable rate. On average, UK Finance says that homeowners having to do this can expect to see a reduction of just under 11 per cent of their disposable incomes through having to take on a much pricer mortgage.

As is always the case, borrowers in lower-income brackets are getting hit hardest. Their refinancing options may be limited by the affordability tests lenders are required to conduct by the Financial Conduct Authority, but maybe also by lenders’ reduced appetite for risk going into a downturn.

Some of those borrowers are inevitably going to find themselves in trouble. Arrears levels aren’t yet at a really nasty level. In fact, they fell overall. But the number of early arrears ticked up for the first time since early 2021. This suggests that the arrears cycle has started to move upwards, in line with forecasts.

Homeowners are, as a cohort, in a far more fortunate position than Britain’s poorest. But the less fortunate among them may still find themselves in a nasty jam over the coming months.

This helps to explain the need to extend energy price support beyond those on universal credit. No government wants to find itself on the horns of a repossession crisis, even if lenders have improved their management of struggling borrowers (although that is going to be put to the test).

If you move beyond universal credit, targetting can get very complicated. What metrics do you use for means testing? Who does the testing (which can get expensive)?

That doesn’t excuse the perversity of the scheme taking shape under Truss. As I have highlighted, freezing energy prices for everyone will provide by the far the greatest benefits to the wealthiest homeowners with the biggest, energy-consuming homes.

While some homeowners are clearly going to need help, the wealthiest among them certainly don’t. And yet they’re going to end up getting more assistance than anyone.

This is why the Resolution Foundation recently mooted the idea of a “solidarity tax”, to redress the balance and to help pay off some of the vast expansion of government borrowing on the cards, is such a good idea.

A fair and just government ought to seriously consider it. But, of course…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments