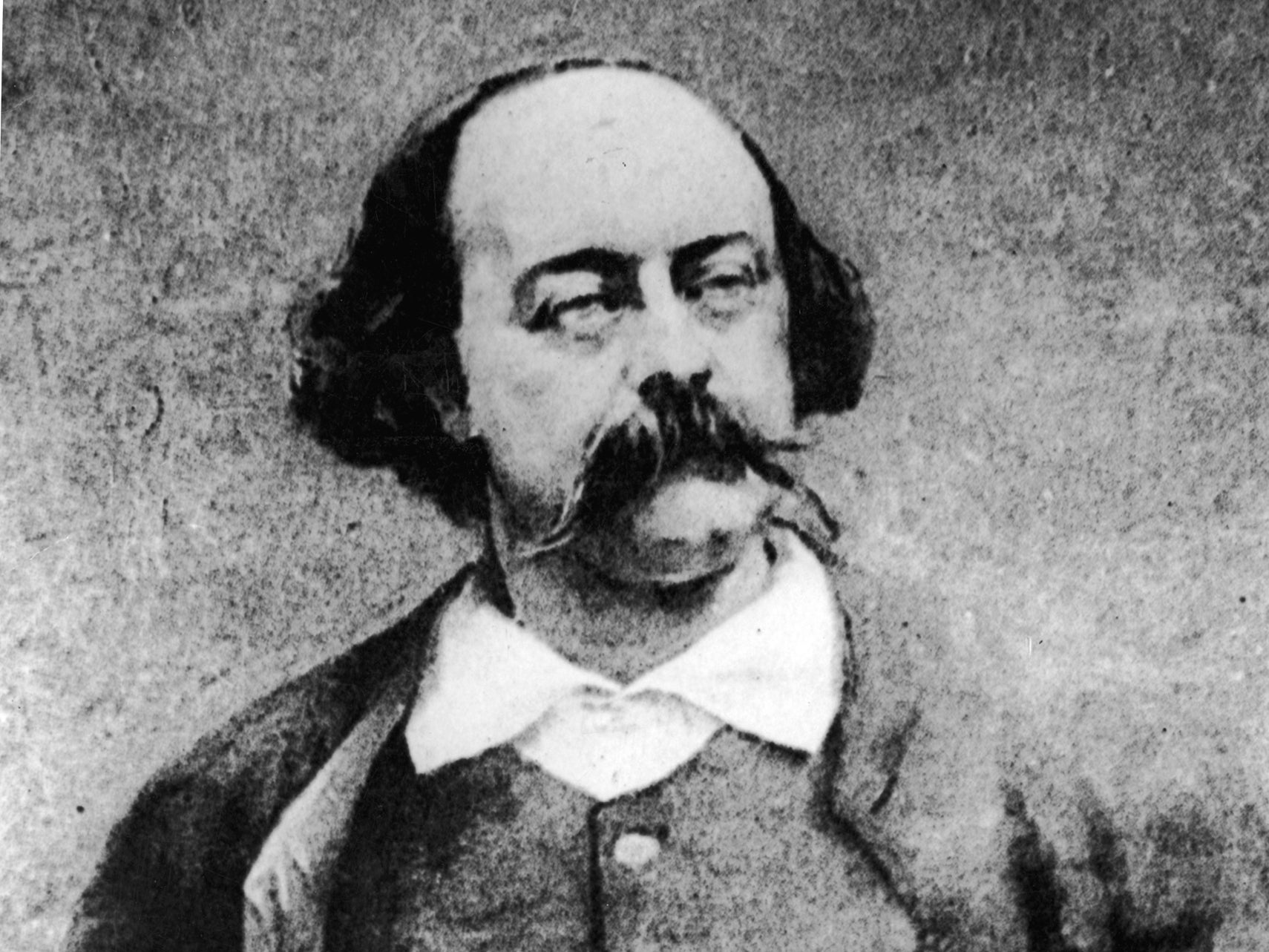

Book of a lifetime: Letters by Gustave Flaubert

From The Independent archive: Ian Sansom on the inspiring correspondence of a writer’s writer

I am, alas, to all intents and purposes, and to my eternal shame, an utterly uneducated, ignorant monoglot. I barely even speak English: I speak Essex. In my mind I sound like Daniel Barenboim delivering the Reith Lectures, or Garrison Keillor, rolling on with another Prairie Home Companion, or Seamus Heaney reciting, or Robin Lustig on the World Service, or WH Auden at the Royal Festival Hall sometime in the late 1960s. But when I speak, I sound like Joe Pasquale. I crush the language. I’ve often tried to learn other languages: Czech; Hebrew; Italian. How else to escape my own voice, and to read the Bible, and Aharon Appelfeld, and Amos Oz, and Bohumil Hrabal, and Dante and Calvino?

I was even lucky enough to go to university at a time when it was still thought fit and proper for a student of English Literature to have a passing acquaintance with the literature of at least one other major European language, so I struggled through three whole years of French. It was either that, fail, or Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic. Studying French, I was in the equivalent of the slow readers’ group. We did mostly gobbets – Victor Hugo, Balzac – but were occasionally encouraged to read entire books. Mostly by Jean-Paul Sartre. Qu’est ce que la litterature? I had no idea. I was a teenager. I had enough angst of my own in English.

I packed away La Nausee on the day I graduated and I don’t think I read a word of French for 20 years, until a few years ago on holiday, when I had trouble with a menu, attempting to order a croque monsieur. I was back to square one. I had regressed. It came as a surprise, then, even to myself, when I recently started working my way – slowly, slowly, pathetically slowly – through Flaubert’s correspondence, in the Gallimard four-volume edition.

With a dictionary at my elbow, late at night, I have been witness – privileged witness – not just to the unfolding of a great writer’s life story, but to how a great writer tells his life story. Freed from the pressure and constraints of a curriculum, it was possible, with pencil and notebook, to track the dreams and ambitions and loves of the writer that Henry James – or someone like Henry James – called the novelist’s novelist.

Everything that one could possibly wish to learn as a writer, about character, about plot, about narrative, about narrativity, is all there in the correspondence, though to be honest I’m more interested in Flaubert’s witticisms and apothegms – the gists rather than the piths. “Art is perhaps no more serious than a game of skittles.” Madame Bovary is a novel “suspended between the double abyss of lyricism and vulgarity”. “I’m a pen-man. I feel through it, because of it, in relation to it, and much more with it.” Flaubert’s letters make me cry. They are humbling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments