Mysterious ‘black widow’ pulsar found just 3,000 light years from Earth

If confirmed, newly discovered system would be ‘black widow’ binary with shortest orbital period yet

Astronomers have observed what appears to be a rare stellar oddity known as a “black widow binary” just about 3,000 light-years away from Earth.

So far, scientists have discovered about two dozen black widow binaries in the Milky Way galaxy, with the newest one named ZTF J1406+1222.

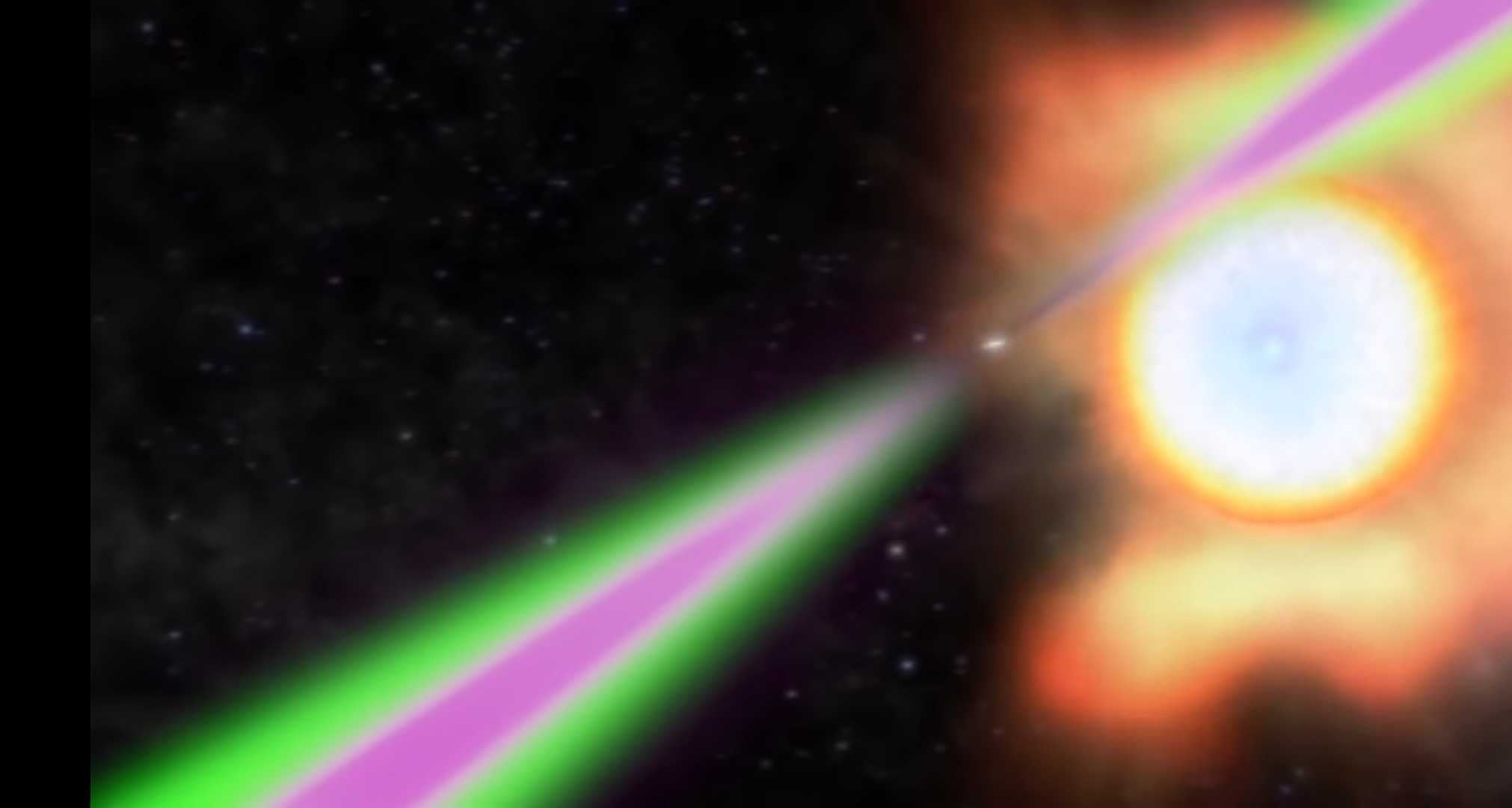

These stellar formations consist of a rapidly spinning neutron star (pulsar) – the core remnant of a collapsed massive star – consuming a smaller companion star.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US say the newly discovered “black widow binary” has the shortest orbital period yet identified, with the pulsar and companion star circling each other every 62 minutes.

They say it is unique, seeming to host a third, far-flung star that orbits around the two inner stars every 10,000 years.

In the study, published on Tuesday in the journal Nature, scientists theorise that the triple system likely arose from a dense constellation of old stars known as a globular cluster.

Astronomers say this particular cluster may have drifted into the Milky Way’s centre, where the gravity of the central black hole was enough to pull the cluster apart while leaving the triple black widow intact.

“It’s a complicated birth scenario. This system has probably been floating around in the Milky Way for longer than the sun has been around,” Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Postdoctoral Fellow in MIT’s Department of Physics, said in a statement.

Black widow binaries are powered by their pulsars, which have a dizzying rotational period of a few milliseconds, emitting flashes of high-energy gamma and X-rays in the process.

Although pulsars often spin down and die quickly since they rapidly burn off a huge amount of energy, researchers say every so often, a passing star can give a pulsar new life.

The pulsar’s immense gravity in such a binary can pull material off its companion star, which would provide it new energy to continue spinning.

Scientists say such “recycled” pulsar would then starts reradiating energy, further stripping the companion star, and eventually destroying it.

While until now gamma and X-ray flashes from the pulsar have been used to detect black widow binaries, in the case of ZTF J1406+1222 it was the optical flashing of its companion star that helped with the finding.

“This system is really unique as far as black widows go, because we found it with visible light, and because of its wide companion, and the fact it came from the galactic center. There’s still a lot we don’t understand about it. But we have a new way of looking for these systems in the sky,” Dr Burdge said.

Due to the constant high-energy radiation that pulsars expose the companion star to, its dayside – the side perpetually facing the pulsar – can be many times hotter than its night side, scientists say.

“I thought, instead of looking directly for the pulsar, try looking for the star that it’s cooking,” Dr Burdge said.

He reasoned that a star whose brightness was changing periodically by a huge amount was observed it would be a strong signal that it was in a binary with a pulsar.

In the study, scientists assessed optical data taken by the Zwicky Transient Facility, an observatory based in California that takes wide-field images of the night sky.

They studied the brightness of stars to see whether any were changing dramatically by a factor of 10 or more, on a timescale of about an hour or less – changes suggesting the presence of a companion star orbiting tightly around a pulsar.

From their analysis, researchers picked out the dozen known black widow binaries, including one whose brightness changed by a factor of 13, every 62 minutes, which they labeled ZTF J1406+1222.

“These systems are not only physical laboratories that reveal the interesting results of exposing a close companion star to the relativistic energy output of a pulsar, but are also believed to harbour some of the most massive neutron stars,” researchers wrote in the study.

However, scientists have not yet directly detected gamma or X-ray emissions from the pulsar in the binary – the typical method by which black widows are confirmed.

So ZTF J1406+1222 is considered a “candidate black widow binary,” which researchers hope to confirm with future observations.

“The one thing we know for sure is that we see a star with a dayside that’s much hotter than the night side, orbiting around something every 62 minutes,” Dr Burdge said.

“Everything seems to point to it being a black widow binary. But there are a few weird things about it, so it’s possible it’s something entirely new,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks