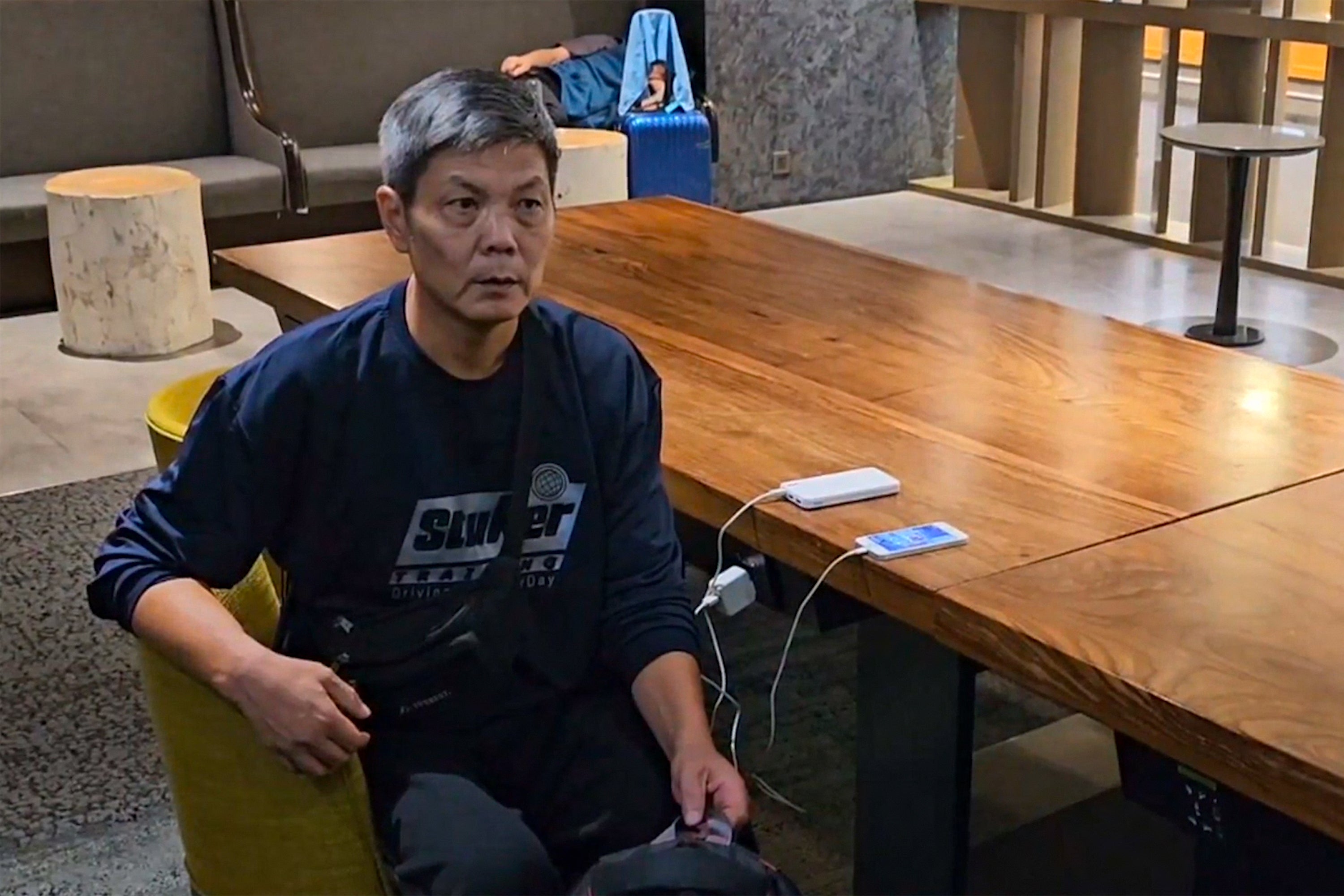

The Chinese dissident living out of a suitcase at Taiwan airport with nowhere to go

‘Crazy’ repression in China forced political activist Chen Siming to flee the country. Maroosha Muzaffar reports on the ‘dangerous and urgent’ situation he now finds himself in

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One day in July this year, Chen Siming received a disturbing call from the police that urged him to undergo a psychiatric evaluation. His crime: being a vocal dissident in China. The phone call made Chen, a well-known political activist, feel “sad, angry and afraid” – he knew he had been on the radar of Chinese officials for quite some time, but this was a worrying new step.

After spending hours at a police station, he returned home and decided it was time to flee China – not an easy decision especially because the pressure and harassment from Xi Jinping’s regime was getting “crazy” and “cruel”.

The activist has now been living off a suitcase in Taiwan’s Taoyuan International Airport at the age of 60 and has refused to budge since last week until he gets asylum in either the US or Canada. In interviews he has described his situation as “dangerous and urgent” and says he is willing to stay like this for months.

Chen is known in his home country for the annual commemorations of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre – a taboo subject there – and his social media posts about the massacre have previously irked Beijing’s authorities.

Police harassment was not new to him either, and he says he has been detained many times in the past. But in recent years, he has noticed a significant crackdown on dissent. On 21 July this year, Chen packed his clothes. He had decided to run.

He first chose Thailand – a country considered a friend of China that has in the past turned in other dissidents to Chinese authorities. But for Chen, fleeing repression was the most immediate priority. He could “no longer continue to accept the ravaging of my personal dignity, the trampling of my honour and the threat to my body”.

The activist travelled from Hunan province down to the southern border with Laos – a distance of almost 1,400km, his bagful of clothes in tow.

Despite it being a notoriously risky route for those fleeing China, Chen decided to make the border crossing by land. After several days of a brutal journey that forced him to cross the Mekong river, he reached Thailand by early August.

But Chen did not feel any sense of ease despite being in a different country. He applied for refugee status with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), but feared even this may not shield him from deportation by Thailand’s immigration authorities or being detained by Thai police.

In 2015, Thai authorities apprehended Chinese dissidents Jiang Yefei and Dong Guangping, who were affiliated with a marginalised Chinese opposition political party. Despite the UNHCR’s objections and subsequent protests, the two were deported to China and later incarcerated. They were arrested in China for criticising the government, while in Thailand they were detained for entering the country illegally.

Several reports say there is a notable rise in the number of Chinese nationals fleeing the country and seeking refuge in the US through an arduous expedition across perilous jungle terrain that spans Colombia and Panama – known as the Darien Gap.

Recent Panamanian government data shows about 400 Chinese citizens journeyed through during the first half of 2022. In November 2022, that number increased to 377, followed by another significant jump to 695 in December. In January this year, an unprecedented 913 Chinese nationals crossed the border, establishing them as the fourth-largest group of migrants to undertake this journey in the current year.

Chen, meanwhile, felt ill at ease in Thailand after fleeing Xi’s repression. He flew to Taipei on 22 September, where he has been since.

Unlike Thailand, Taiwan shares an icy relationship with China given it continues to assert its status as a self-governing democracy, while Beijing claims it as part of its own territory and has said it will bring about “reunification” with the island by force if necessary.

In a video he posted on X/Twitter, Chen said he was in the transit area at the Taoyuan airport to escape Chinese political persecution.

“The Chinese police’s stability maintenance methods directed towards me were becoming more and more cruel and crazy,” he wrote.

They detained me at will without following legal procedures, taking my cell phone and even giving me a psychiatric evaluation. I can no longer continue to accept the ravaging of my personal dignity, the trampling of my honour and the threat to my body.

Chen pleaded for help seeking asylum, saying his situation is “dangerous and urgent”.

“To avoid the political oppression of the Chinese Communist Party, I have now come to Taiwan.

“I hope to receive political asylum from the US or Canada. I ask friends to call on the Taiwanese government to not send me back to China,” he said in a video, adding in the caption: “I am forced to be illegally stranded here.”

Chen said in an interview with The Guardian that he is “willing to wait for months” at the airport terminal to escape the wrath of Chinese authorities.

“I am willing to wait for months because I feel safe in Taiwan. I want to go to the United States. I think Taiwan is very safe and there are no security problems. Taiwan has democracy and liberty as its shelter, so Taiwan is safe for me personally. But security is not my first option in where I settle, I have a lot of work to do in the US,” he said.

Chen was in transit from Thailand to China’s Guangzhou, with a layover at Taoyuan airport on Friday. But he chose not to board the second flight and declined requests to return to Thailand due to concerns about a possible deportation.

This is not the first time a Chinese dissident was stranded in a Taiwanese airport. In 2018-19, Chinese dissidents Yan Bojun and Liu Xinglian found themselves spending four months in the transit area of a Taiwanese airport.

They had come from Thailand like Chen but refused to continue their journey to Beijing. Eventually, the UNHCR granted them temporary asylum status and, after a long standoff, Yan and Liu departed for Singapore.

They were later permitted to return to Taiwan legally – this time on short-term humanitarian visas. Ultimately, they resettled in Canada.

China has become stricter when it comes to arresting dissidents, even when they flee overseas.

Beijing has established overseas police stations, issued rewards for the capture of critics who sought refuge abroad, coerced members of the Chinese diaspora into acting as informants and succeeded in detaining or deporting exiled individuals living overseas.

More recently, 50-year-old Chinese human rights attorney Lu Siwei was forcibly returned to China after being arrested in Laos while on his way to reunite with his family in the US.

“Sadly, Chinese human rights lawyer #LuSiwei was deported back to China, according to his lawyer in Laos. We should continue to put pressure on China, calling for his release,” Tokyo-based human rights activist Patrick Poon wrote on X/Twitter.

Lu’s wife Zhang Chunxiao told Radio Free Asia earlier this month that she fears for her husband’s safety. “The thing I feared was suddenly right there in front of me. Before that, it just had a vague existence [in my mind], but then I saw all at once, saw clearly that this was real.”

She said her husband will probably be “tortured” in a Chinese prison.

“What is really threatening is that China has increased its reach into neighbouring states, and also well beyond that. Nowhere is safe,” Eva Pils, a law professor at King’s College London who studies human rights in China, told the New York Times in late August when Lu’s case was talked about in the international media.

“That poses many threats to the individuals concerned, it undermines the ability of other governments to keep people within their jurisdiction safe.”

Chen was still at the airport on Monday.

“With regard to the matter of Chinese dissident Chen Siming being stranded at the Taoyuan International Airport, the government is currently working on it, and is not able to share relevant details,” Taiwan’s mainland affairs council told CNN.

Rights group Chinese Human Rights Defenders has urged Taiwan to help Chen in seeking asylum. “If Chen Siming is returned to China, he faces an almost certain risk of detention, torture and other ill-treatment, and an unfair trial,” said William Nee, the group’s research and advocacy coordinator.

E-Ling Chiu, the national director of Amnesty International Taiwan also urged Taiwan to help him. “If the Taiwanese government takes a deportation position, they can send him back to Thailand. But if they deport him back to China, it will violate the non-refoulement principle. It’s not acceptable.”

Chen’s journey might get slightly complicated as Taiwan does not have a formal refugee policy.

According to the 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Taiwan authored by the US State Department, “the law does not provide for granting asylum or refugee status, and authorities have not established a system for providing protection to refugees”.

“Due to its unique political status, Taiwan is not eligible to become a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” said the report.

“Given the current political climate in China, there is no space for me to operate there,” Chen told CNN.

“I hope the US government will stand with the Chinese people, and help bring an end to the authoritarian rule of the Chinese Communist Party so that China has democracy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments