The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

BBC’s Justin Webb: ‘Everyone’s terrified of discussing trans issues, but we have to speak freely’

He’s a BBC lifer, but Justin Webb – who tells Julia Llewellyn Smith his own childhood was ‘absolutely bloody miserable’ – isn’t afraid of being outspoken about the way adults confuse and upset children about sex, gender and sexuality

There’s no question that Radio 4 Today presenter Justin Webb had a terrible childhood. Now 62, he was brought up in Bath by his mother and his schizophrenic stepfather, who – despite being “eccentric to the point of being frightening” – never received medication for his condition, and whose later diagnosis came in the form of a blunt GP pronouncement: “I regret to inform you your husband is stark, staring mad.”

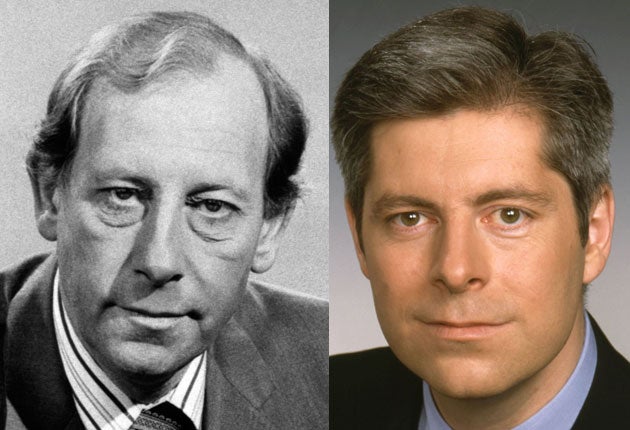

Webb was eight years old when he found out who his real father was. Watching newscaster Peter Woods present the BBC news, his mother simply nodded at the screen, said “That’s your father”, and left the room. There was no further discussion. Over the years, Webb gradually learnt how he had been born as the result of an affair when his mother was working as a secretary at the Daily Mirror (she was sacked for becoming pregnant). But Woods (who died in 1995) was married with a family, and only met his son once, when Webb was a six-month-old baby.

Webb recounts all this – plus his seven years in a “hellhole” boarding school riven with violence and neglect – in his memoir The Gift of a Radio: My Childhood and Other Train Wrecks. It sounds like a classic misery memoir, yet his tone isn’t remotely self-pitying; in fact, if anything, it’s faintly comedic. “I really did write it for a laugh, because the 1970s were funny times,” he agrees, sitting in the study of his house in Camberwell, in south London.

Outwardly at least, there appears to have been little lasting damage. Webb has had a successful 39-year BBC career, including spells presenting BBC Breakfast and as North America editor. His solid 27-year marriage to PR Sarah Gordon, complete with three children (boy-girl twins aged 23 and a daughter of 19), couldn’t be further from his own backstory. In person, he exudes amiability, however serious the conversation. He wonders if his success in part owes to the keep-calm-and-carry-on ethos imbued in him but actively discouraged today.

“In many ways, the stiff upper lip is risible, and possibly harmful, but [today] there is an absolutely horrific amount of mental distress among modern teenagers. When you look at modernity, we’re all encouraged, in a narcissistic way, to think and talk endlessly about ourselves, but there’s a kernel of truth that says, if you examine yourself too much, particularly as a child, it doesn’t lead to anything very good.”

“If someone had asked me if I was happy when I was 11 and I’d thought about it, it would have really brought home to me that I was absolutely bloody miserable,” he continues. “I’d have thought, ‘Jesus, my stepfather is trying to kill himself upstairs. We live in this ghastly little house. My mum’s obviously upset. I’ve got nothing going for me. I know my father is on TV, but I’ll never meet him.’ But nobody ever did ask, and we just got on with it. Britain was a weird, dingy, coal-smoke-infested place, and yet we were happy... in some respects, happier than we are now.”

“There were some kids who were abysmally abused in the 1970s, and we’re very aware of that, but – generally speaking – we certainly didn’t confuse and upset children with adult issues in the way we do now,” he continues.

“We’ve just found a different way of being abusive to kids. We have a generation of children who are just as messed up as we were – in fact, more so, [owing to] social media, phones, a lack of boredom in lives, and identity politics that imposes a psychological burden on kids – ‘What gender are you? Would you please think about your sexuality, even though you are not old enough to understand sex, or indeed to have it legally? Are you happy? Etc etc etc. We were left alone – probably too much – but at least we were spared the oppression of endless introspection!”

Questions surrounding gender identity are clearly close to Webb’s heart. On Saturday, in his role as guest curator at this year’s Cheltenham Literary Festival, he’s chosen to chair a session titled The NHS: A Culture of Cover Up, with Caroline Wheeler, whose book, Death In the Blood, documents the scandal of the 5,000 people in the UK infected with hepatitis or HIV from contaminated blood during NHS procedures.

But he’s more interested in promoting the work of the other writer on his panel – his BBC colleague Hannah Barnes, the author of Time to Think: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Tavistock’s Gender Service for Children, investigated the (soon to be closed) NHS Tavistock gender identity clinic, which issued puberty-blocking hormones to numerous under-16s. A report of an investigation conducted by the former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health found that patients were “at considerable risk” from the “unquestioning affirmative approach” favoured by clinicians.

“It’s a brilliant book of impartial journalism, that’s been enormously influential in having the Tavistock closed and a rethink about how we treat children, and potentially adults, with gender dysphoria,” says Webb. “I thought it important Hannah got a chance at a major literary festival, because people shy away from this subject because they’re afraid of bullying or being bullied. Everyone is genuinely terrified, but we’ve got to be able to speak freely about these things.”

It’s not the first time Webb has caused controversy while addressing this fraught topic. Last year, he was “partially rebuked” by the BBC after four complaints were received over his comment that the academic Kathleen Stock had been “abused by students who accuse her, falsely, of transphobia” – the issue being with the “falsely”. “I was quoting in our newspaper review from something someone else had said. But the point is, people have got to be able to talk about these things openly, and they’re too scared.”

Is Webb worried he’ll be cancelled? “I’m not, actually. [Transgender issues have] become so heated, and obviously used by politicians and by people who want to shout and scream, but I think most people are simply a bit worried about where it takes us, and there are legitimate fears about where children – particularly troubled children – stand.”

This willingness to draw attention to himself over such a contentious issue is surprising: as a self-described BBC “lifer”, he’s normally impeccably unbiased, limiting tweets to promoting his book and commenting on rugby (he’s a passionate fan). “Working in news, quite properly I’m constrained as to what I say online. Who cares what I think – I don’t even care!” he says, laughing. “I’m really interested in old-fashioned impartiality.”

Yet neutral doesn’t equate with bland. Webb is energetically damning as he talks about how commercial news organisations, and presenters such as Piers Morgan, are increasingly relying on shock-jockery for ratings.

“It’s encouraged, and for the individuals concerned, it’s often a money spinner. You look at America, at people like [former Fox news host] Tucker Carlson, and on the left, the people who work for MSNBC, who build personas on the basis of taking quite extreme, unkind, unfactual positions. [But] if we go down that road, we lose something. [BBC news chief executive] Deborah Turness has said she wants the BBC to be a proper town square – not a so-called free-speech free-for-all, where people insult and denigrate each other, but a place where people can come and bring opinions, and facts, and beliefs, and discuss them. That’s why, until we can find some way of replacing it, the BBC seems to be as vital as it’s ever been.”

Such loyalty is increasingly rare. In the past few years, many of Webb’s BBC peers – think Andrew Marr, Graham Norton, Dan Walker and Vanessa Feltz – have escaped to the commercial sector, lured by the double whammy of higher salaries (which aren’t published) and free expression. Last year, news colleagues Jon Sopel and Emily Maitlis left to start their hugely successful The News Agents podcast. Webb’s salary is between £255,000 and £255,999 – less than that of other Today regulars Amol Rajan, Nick Robinson, Mishal Husain and Martha Kearney – but he still claims he’s not tempted to jump ship.

“I think there’s still something wonderful about the range of the BBC. We’ve lost a little bit of our audience recently, because of all the competition, but there are still millions and millions of people listening at the same time, and the fact of it being live gives it a kind of jeopardy that makes it so interesting.”

Webb inherited the BBC’s Americast podcast from Maitlis and Sopel, which he co-presents with Sarah Smith and Marianna Spring, yet he’s plainly not wild about the medium, wary that podcast audiences only listen to presenters whose views they share. “The danger is that you then get everything seen through the filter of your prior beliefs. Some people are angry with us when they have to listen to the Today programme, and to people with whom they disagree.”

On this topic he’s (politely) heated, but on the future of the BBC, Webb’s unruffled. Recent corporation scandals – such as allegedly turning a blind eye to inappropriate behaviour by one of its highest-paid presenters, Russell Brand (who denies any wrongdoing) – have little impact on the day-to-day life of its foot soldiers. “[Foreign editor] Jeremy Bowen and I started as BBC trainees on the same day in 1984, and we’ve seen dozens of crises – some very serious – come and go. The BBC is a really important part of the nation, and along with the territory comes putting out fires. But at least it admits when it gets things wrong, and deals with its own dirty laundry.”

Justin Webb will be appearing at Cheltenham Literature Festival on Saturday 14 October 2023 https://www.cheltenhamfestivals.com/literature

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments