Billy Crudup: ‘Pouting is not the way of the future. Our kids are fighting and talking it out’

He’s been called the ‘leading man that almost was’, but the actor has bounced back as slithery TV exec Cory Ellison in Emmy-winning series ‘The Morning Show’. As it returns to Apple TV+ this week, he tells Helen Brown about power dynamics, privilege, and finding his way through the culture wars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During the pandemic, Billy Crudup knows that most of us escaped “the confusion, anger, boredom and general distemper” by embracing the alternative realities of big, glossy TV series. So it comes as a shock to see the virus make the first jump to drama in the opening frames of The Morning Show’s season two. After the speed and emotional intensity with which characters ricocheted off each other in the high-stakes, newsroom environment of the first season, Crudup knew it would be “uncomfortable” for viewers to sit with the tumbleweed images of lockdown New York.

But “watching the writers televise the pandemic in real time was so tense and thrilling”, he says. “I felt the same watching them navigate the nuances of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements in season one, constructing a narrative as real-life events were unfolding. It’s unlike anything I’ve been a part of before.”

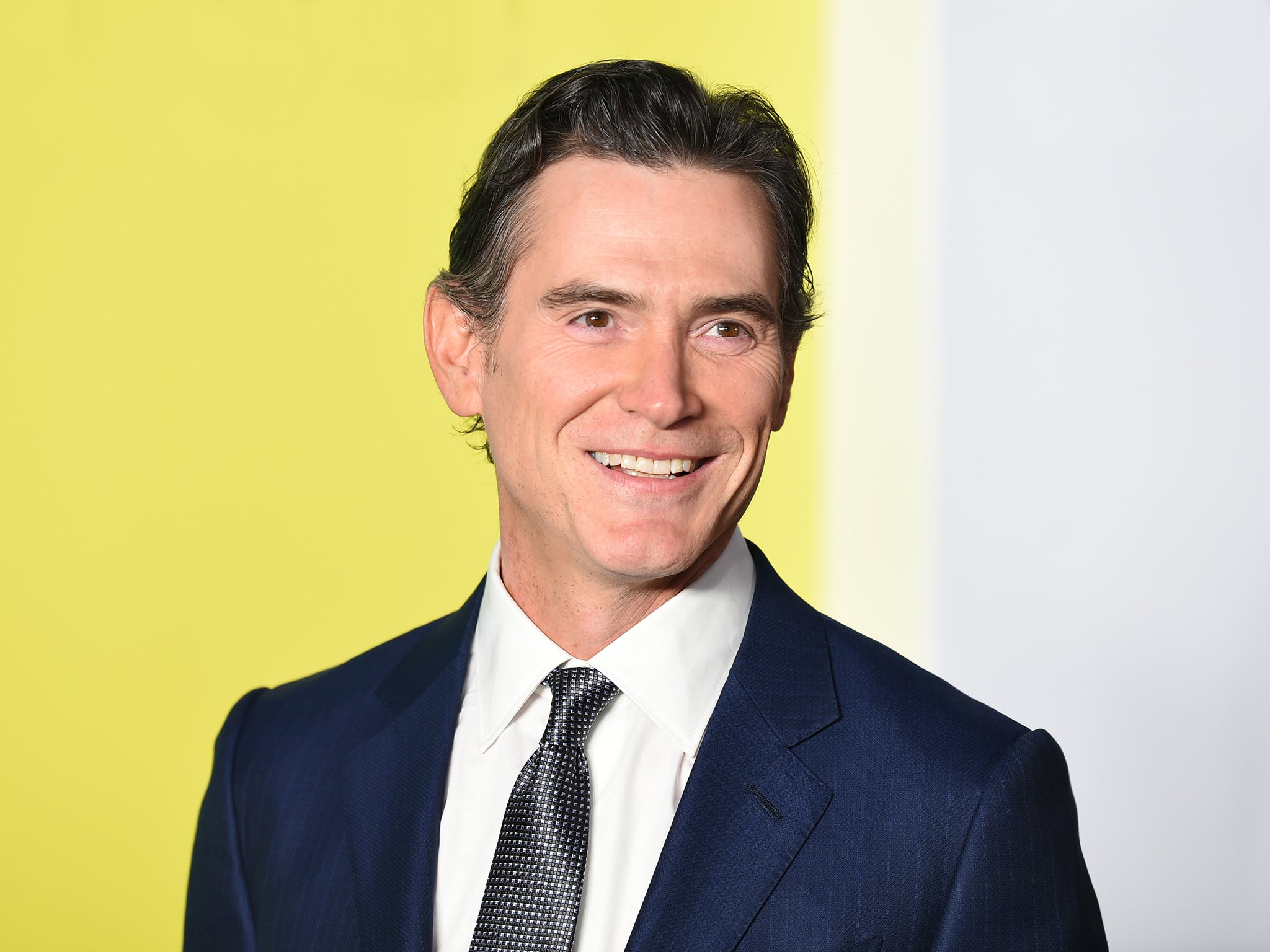

Rubbing his hands and leaning enthusiastically towards the camera – “thrilled to talk about the show!” – the 53-year-old doesn’t look like a guy who feels uncomfortable a lot. By the looks of his IMDb page, he stopped doing that some time ago. The LA Times once called him “the leading man who almost was” in reference to the succession of star vehicles that followed his turn as moustachioed rock babe Russell Hammond in 2000’s Seventies-set drama Almost Famous. But being the star attraction never really suited him. Now he’s become synonymous with slippery supporting-role sorts – such as lawyer Eric MacLeish in the Oscar-winning smash Spotlight – as if he’s having his own McConaissance without having to suffer the flaccid romcoms first.

Speaking over Zoom, Crudup exudes the confidence and curiosity of a guy who only takes parts that interest him. And it’s paying off: in The Morning Show, his unpredictable TV news executive Cory Ellison was hailed by The Guardian as “the single best television character of the year”, and he was nominated for an Emmy for the role in 2020, too.

For those who haven’t yet sucked up the subscription fee for Apple TV+, the first, 10-part season of the streaming service’s flagship $300m series aired in 2019 (and it returns, finally, this week). It told the story of TV anchor Alex Levy (Jennifer Aniston) as she struggled to retain her position at a leading TV news programme after her long-time co-host Mitch Kessler (Steve Carell) was fired over allegations of sexual misconduct, his replacement being wildcard southern conservative Bradley Jackson (Reese Witherspoon).

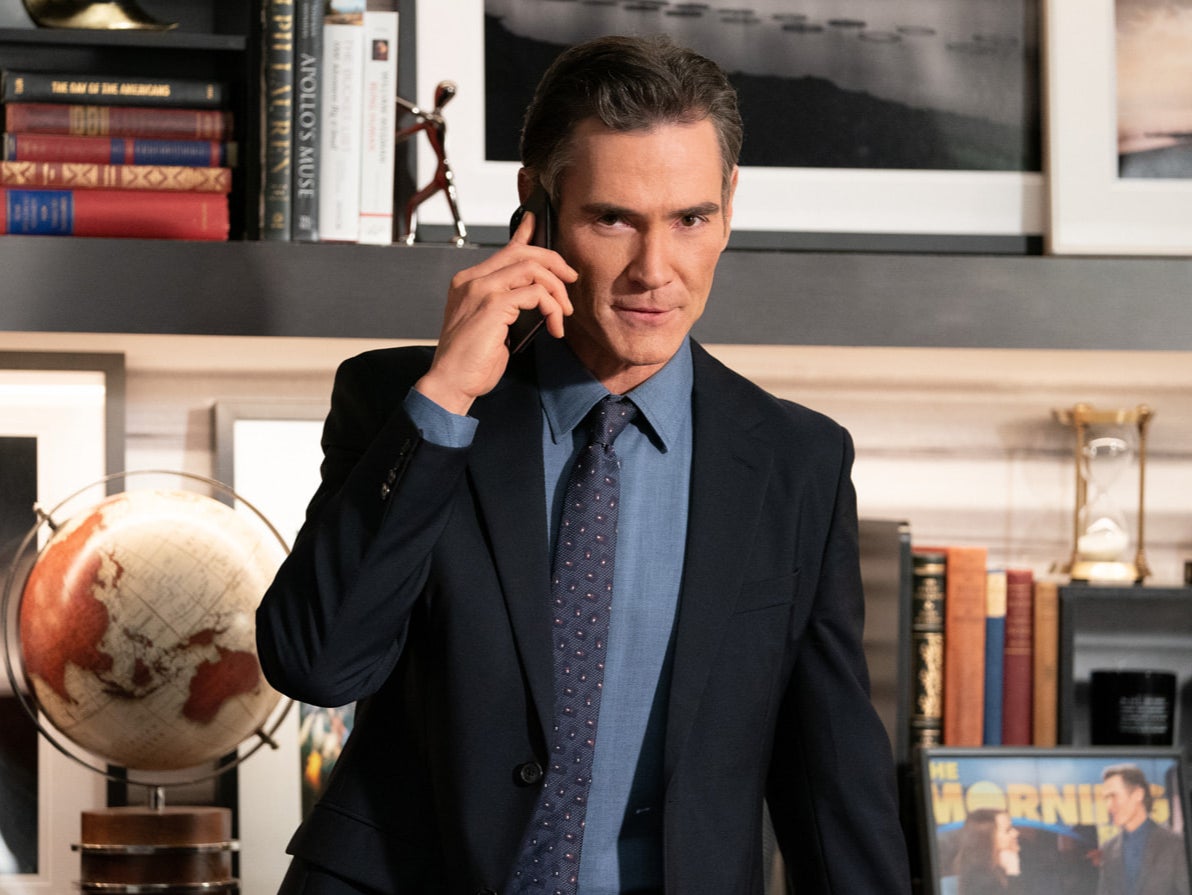

Crudup’s Ellison is entirely compelling, causing chaos just for the hell of it. Initially, he is seen telling colleagues that Aniston’s character is “past her sell-by date”, but then he is delighted to be proved wrong. He’s capable of genuinely applauding her status as a “feminist icon” while cashing in on the ratings spike when she unravels on air. “People are just getting too used to their favourite cuddly men turning into monsters,” croons the actor, “but watching a beloved woman’s breakdown is timeless American entertainment.”

“He’s a punk,” grins Crudup. While the show’s other straight, white men in suits act in their own interests, Ellison is the network’s Loki. He’s often shot from behind, leaving viewers guessing what’s going on in a mind that functions with the amorality of a social media algorithm, on a constant quest for more kicks and clicks. When we see his face, it’s often split with an unsettling grin, bracketed with laughter lines almost as deeply set as The Joker’s. “I had those put in especially for the character,” deadpans Crudup. “Anything for a good part.”

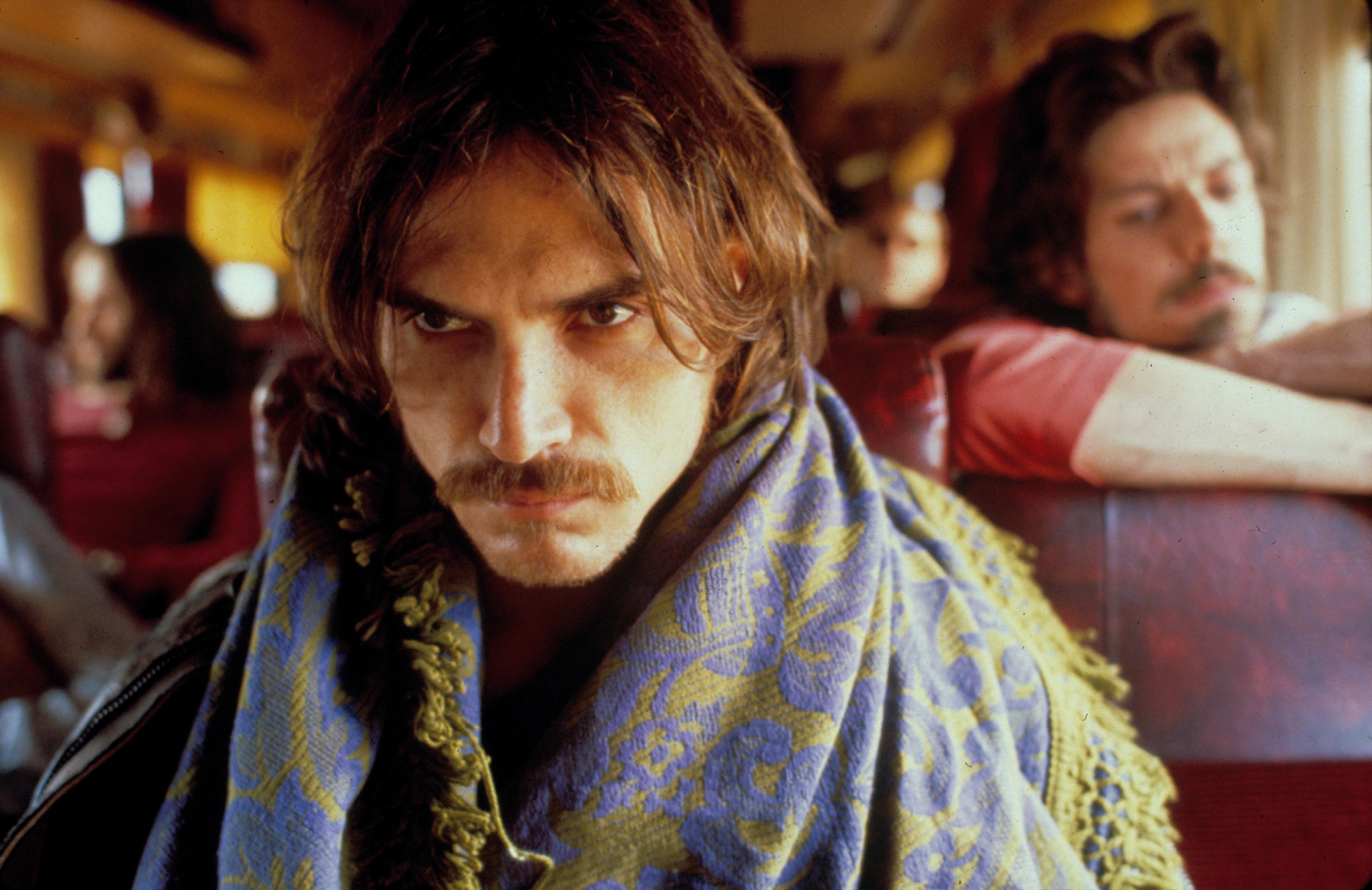

He shares a degree of Cory Ellison’s curiosity about what happens when a man pushes against expectations. Highly educated and articulate, Crudup says he struggled with the “lack of versatility” in the leading-man roles he has been offered, and that he is instead attracted to “inscrutable characters”. He was always better at the leftfield stuff: a heroin addict called “F***head” in 1999’s Jesus’ Son, the foremost female impersonator of the 17th century in Strange Beauty (2004), and a philosophical superhero in Watchmen (2009). Known by fellow actors as “a quiet presence on set”, he has said that he took the latter role (after Keanu Reeves dropped out) “because it was a subversion of the superhero genre... Dr Manhattan has no interest in saving humanity. He wants to go to Mars and think about physics. Badass!”

More recently, he won over a new generation of multiplex audiences in Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant (2017) and wowed theatre critics with his solo off-Broadway turn as a pathological liar in Harry Clarke in 2018. The New York Times praised the “vulpine charm” that “makes it impossible not to like him, even as he grows alarming”. Aniston, with whom he shares a manager and an agent, saw him in the role and later told The Hollywood Reporter: “I remember leaving the theatre and turning to my producing partner, Kristin Hahn, and saying: ‘I don’t care in what capacity, Billy Crudup has to be in The Morning Show.” The show’s writer, Kerry Ehrin, had imagined Ellison as a 30-year-old young gun, but Crudup flew out to LA to convince her of his vision for the role.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Crudup felt he had encountered more than his share of Ellisons at galas and charity events. He’d sometimes watch as they scanned the room for the person in a position of power, sussed them out and then tried to win them over. As a New Yorker, he felt intensely attuned to the “capitalistic ambition” that Ellison shares with everyone from pavement level hustlers “selling sunscreen on the subway to the guys who are running Wall Street”, he says.

Crudup’s own father – Thomas Henry Crudup III – was a hustler with “an appetite for instability”. He rolls his eyes at the memory of the many childhood Saturdays he spent “wading through the stuff he had bought from markets and garage sales to sell on at a tiny margin”. Although he can laugh about it now, his childhood was chaotic. He spent the first eight years of his life in a suburb of Long Island before the family relocated to Texas, then Florida. His parents divorced, remarried, then divorced again.

“I’m doing another show for Apple called Hello Tomorrow, which has elements of my father’s character,” says Crudup. “The guy is selling timeshares on the moon, although it’s unclear if the timeshares are there or not. And that sort of uncertainty was part and parcel of how I grew up. A character like Cory would see anything like that as not worth his time. My dad was operating at the $20-$30 level, and Cory wants to go into the most intense environment he can find in this capitalist system and play some high-stakes corporate poker games. He’s playing at the $250-300m table. We haven’t seen him at the billion dollar table yet…”

‘I usually obfuscate things about my private life’

At the end of season one, we saw Aniston’s Alex Levy melt down in front of the cameras and Cory Ellison elevated from head of network news to CEO. It’s disconcerting to find Crudup’s rebel character (his backstory involves being raised by a powerful single mother who worked in politics) accessorise himself like a classic member of the patriarchy. He lives in a hotel suite that’s all dark-wood panelling, reminiscent of the Trump Tower locker rooms that became a “safe space” for all that sexist macho “banter”.

“That surprised me too,” says Crudup. “It was weird to find Cory a little knocked off balance by the promotion. What I think ends up happening to people who ascend to positions of power is that their vocabulary changes. In order to talk to the board of the company with authority, a certain pantomime is required. Cory’s revolutionary discourse about the way things should be becomes overwhelmed by the theatre of navigating those situations. He thinks: OK, what can I compartmentalise enough so that I can still make the changes I want to make? To get through our lives, every one of us has to make accommodation for those whose worldview we might find distasteful…”

Crudup pauses and grins a Cory-grin again. “My character has a superpower in all of his privilege. He uses it to get into that locker room and make those guys feel safe. But he might be there to steal their shoes and sell them. He wants to use all the trappings of being a straight white affluent male to get into the house of power, then rewrite the rules. Infiltrate and reorganise is his plan.”

I ask Crudup if that’s part of his own, personal plan. He’s an affluent, straight, white man. When did he last use that power to do something disruptive? He laughs. “Good question! If I tell you the first thing that comes to mind then I’m revealing things about my personal life… and I usually obfuscate…”

Crudup never likes to talk about his private life. He had an uncomfortable brush with red-top fame when he left his partner of eight years (actor Mary-Louise Parker) in 2004, when she was seven months pregnant with their child, for Homeland star Claire Danes, with whom he co-starred in Stage Beauty. He speaks rapidly, in complete, tightly sprung paragraphs, which I suspect he knows are hard to interrupt, limiting the number of questions a journalist is able to tilt at him. So he takes a moment to find “an example from my civilian life… OK. What I can tell you is that I am the member of the board of at least one company, and I am not the easiest person on the calls. When people are making decisions of consequence I don’t want them to take anything for granted.”

The implications of the coronavirus pandemic are certainly taken for granted in season two of The Morning Show. Although the network sends its marginalised black, gay presenter to China, he’s frustrated to see his reports are often bumped from the programme. His anger – classically Morning Show – is a tangle of ego and grievance. (Does he really lack the charisma to earn a major anchor job? Or are his bosses masking their racism and homophobia?) The American public’s lack of interest in world events and science is also pilloried: the show’s producer says that when they run reports from Wuhan she can “hear people turning off in Wyoming”.

Of the culture wars, which are explored with real wit, humanity and nuance in the series, Crudup says: “There is no question that experiencing the framework of the world change in my fifties makes me feel my age. I feel it in every step I take. It’s almost as though somebody comes up and says: you’re walking wrong. They don’t exactly say why, or what it is you’re doing wrong. They have some ideas about your pace, and your cadence, but they’re all a little bit confusing. And all of a sudden, you’re thinking about your walking all the time. We have built up decades of experience getting through the world in a certain way…”

These ideas are powerfully interrogated through the character of Mitch Kessler. He’s a guy who has had what he considers to have been consenting affairs with junior staff members at work. He doesn’t see himself as a rapist. He comes from a time when male power was considered an acceptable aphrodisiac, and is bewildered by the ways in which he is being punished for playing by rules he thought were socially acceptable. He’s horrified to be lumped in with creeps and paedophiles. He has a huge ego, and he doesn’t fully know how to own his privilege. But, to his credit, he’s trying.

Season two finds Mitch in exile (albeit a palatial one) in Italy. There he’s accosted by a young woman who tries to shame him at a public cafe. Unexpectedly, it’s another woman who springs to his defence. She tells him: “We can’t live our lives worrying what children think of us. She [the younger woman] doesn’t know what she wants from you. If you apologise, it’s insincere. If you do good for the world, it’s self-serving. If you dare to live your life? The gall! If you choose to die, you’re taking the coward’s way out. You must live and suffer, but you mustn’t do it in front of us and you mustn’t try to learn. There’s no safe space from safe spaces.”

This woman is middle-aged, like Crudup. He has sympathy with people who feel: “‘Man, I got through the hard part of life. Why do I have to change now?’” he says. “That seems a hard thing to ask. It isn’t always the most comfortable thing to do.” But he sees the comedy in it. “As the revolution in workplace power structures progresses we hear voices resisting with: ‘I like the way things are!’ People can get super angry about it and wave their banners about ‘not taking it anymore’, which is of course a hilarious response to a movement about not taking it any more.”

Crudup struggles with it all, too. He jokes that “there are days when a prefrontal lobotomy sounds better than a martini… I do get tired”. But he’s also an optimist. “The dialogue at the moment is clumsy,” he says. “But pouting is not the way of the future. Our kids are not pouting. They are fighting and talking it out. They are growing their understanding of the potential of our society. They are asking the same thing of us that people their age have always asked of people my age.”

He says he has hope that, “even if it takes five, 10, 20 years”, the progress “won’t all be painfully self-conscious. Because it appears to me that, in the broad scheme of history, we are moving more towards equity than away from it.” Does he think guys like Ellison are helping us to move in the right direction? “We’ll have to wait and see.”

The Morning Show, season two, is out now on Apple TV+

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments