Rock, groupies, golden gods and that Quaalude kiss: Almost Famous at 20 by the stars and director who made it

Cameron Crowe, Kate Hudson, Billy Crudup and Patrick Fugit talk to Patrick Smith about the classic film that captures the Seventies rock scene

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In late 1972, a writer called Cameron Crowe rang the offices of Rolling Stone with a scoop about Bob Dylan. They ran the story. What no one in the office realised, though, was that the author was only 15. Within two years, this precocious teenager from San Diego had become the youngest person ever to write a cover feature for the magazine, and was following bands from The Who to Led Zeppelin on tour, a buoyant insider high on the fumes of their jet-set lifestyle.

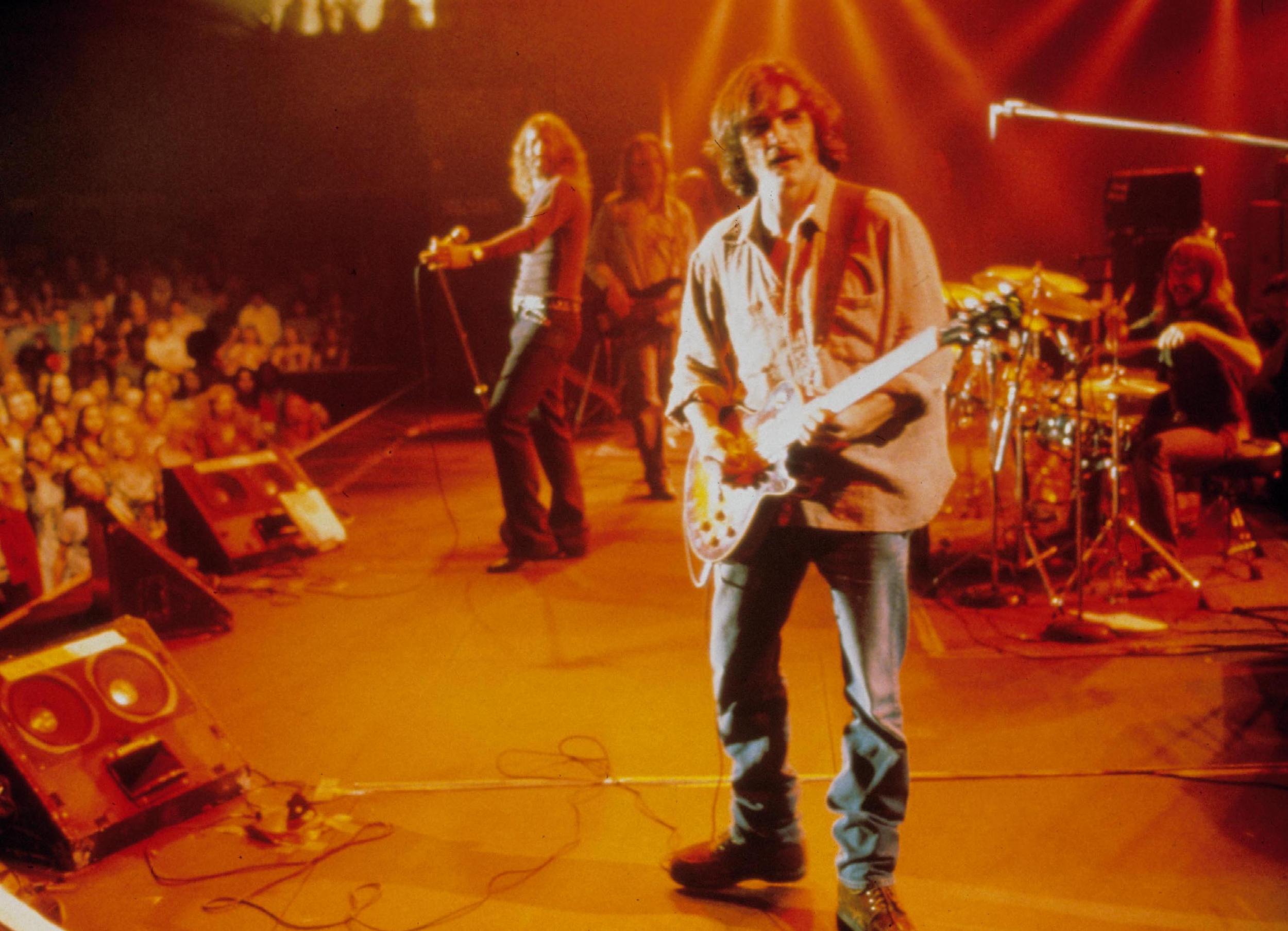

If this sounds like the plot of a film, that’s because it is. Almost Famous, released on 13 September 2000, was written and directed by that same Cameron Crowe, by then a household name thanks to his Oscar-winning drama Jerry Maguire (1996). Loosely based on Crowe’s own teenage adventures in rock journalism, Almost Famous is set in 1973 and follows his alter ego William Miller, a cherubic young writer who’s taken under the wing of legendary rock critic Lester Bangs (Philip Seymour Hoffman), then lands a dream commission to go on the road with the mid-level band Stillwater (a fictional hybrid of the Eagles and Lynyrd Skynyrd).

“I am probably as protective of Almost Famous as I am anybody on Earth,” Crowe tells me. “It’s a movie about family and loving music, and I remember thinking throughout, ‘I’m directing this with so much love – I really hope it shows up on screen.’” It does. Thrumming with the exuberance of youth, Almost Famous is a gloriously sweet-minded story, a tie-dyed paean to lost innocence and the music that shaped and defined a generation before the industry was hijacked by marketing men.

“It’s very rare in anybody’s career to be part of a truly classic film,” says Kate Hudson, Oscar-nominated for her role as the self-styled “Band-Aid” Penny Lane. “But 20 years on, I can now objectively say: Almost Famous is truly a classic film. It’s one of the best scripts I’ve ever read.”

Winning the Oscar for best original screenplay, the film captures not only the early Seventies rock scene through the eyes of an idealistic kid – the touring, the glamour, the drugs, the groupies – but also the pangs of betrayal and unrequited love. Crowe, in laying his soul wide open, doffs his hat to Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses and The 400 Blows: beneath the gentle slapstick and satire you’ll find bittersweet truths. There’s a charmed sense of adventure to it all.

“Cameron has a wonderful way of romanticising the things in life that we all go through,” says Patrick Fugit, who stars as William Miller. “Which is why his films – like Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and Say Anything (1989) – resonate with me, with my kids, with my parents. The things that William Miller goes through connect with people who were interested in journalism; people who fell in love; people who were a genuine fan of something. Of course, there are dark sides to all these things, but Cameron is this stalwart observer of the romantic. That heart, that romanticism, that optimism permeates Almost Famous.”

Billy Crudup, who plays Russell Hammond, Stillwater’s would-be rock-god guitarist, agrees. “Many of us are nostalgic about huge transitions in our lives,” he says. “And it’s infectious getting to see somebody who is on the cusp of young adulthood try to manage such an exotic and thrilling atmosphere, in all the ways we want to imagine the rock’n’roll lifestyle.” Crowe, he continues, coaxes such “remarkable performances from his actors that he creates a beautiful tapestry that everybody has some connection to. He doesn’t alienate the audience by taking himself and the subject matter too seriously.”

That’s not to say he took the film lightly. Although he’d had a rough version of the script since the late Eighties, it was only after the surprise success of Jerry Maguire – it grossed $274m (£220m) and was nominated for five Oscars, winning for best supporting actor (Cuba Gooding Jr) – that Crowe felt ready to distil all those personal experiences into a 172-page hymn to the wild-eyed scene that erupted between Sixties hippie idealism and punk nihilism. He showed the screenplay to Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, the heads of production at DreamWorks, who in turn had Steven Spielberg look over it. “I read your script,” Spielberg told Crowe down the phone. “Shoot every word.”

So he did. Handed a $60m budget by DreamWorks, he set about meticulously assembling his cast. Or reassembling it, in some cases. “Brad Pitt worked on the movie for about four months,” recalls Crowe. “He wanted to play a musician and was a blast to work with”, but he ended up passing on the role of Russell Hammond six weeks before filming was to begin.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Elsewhere, Crowe considered Rita Wilson for William’s querulous, overprotective mom, but ultimately opted for Frances McDormand, whose funny, fretful performance would earn her an Oscar nomination. As for Penny Lane, Sarah Polley was originally down to play her, but when filming was delayed, she moved on. Though Kate Hudson had already been cast as William’s older sister – a part that would eventually go to her old school friend Zooey Deschanel – she asked Crowe if she could audition to replace Polley.

“It was the most treacherous auditioning process I’ve ever been through,” Hudson remembers. “I mean, audition after audition after audition. At first, Cameron was reluctant to give me Penny; he saw me as the sister. But Gail Levin [the casting director] was a big cheerleader for me. At the time, I was shooting a film in Ireland, so I was having to fly back and forth to these auditions. I did four, I think. I remember on the third time of going home, I called my mum [Goldie Hawn] and told her I didn’t know where I was any more. I was only 19. I was so independent so fast. I’m like, flying across the world and really wanting this job. Anyway, it paid off.”

In what was her breakthrough role, Hudson inhabits the free-spirited Penny Lane with such ethereal ease that it’s all the more heartbreaking when you discover a bruised melancholy under that carapace of self-confidence. Adored by William, adoring of Russell – even when he trades her in for 50 bucks and a case of beer in a poker game – Penny is the emotional fulcrum on which the drama turns, with Hudson delivering every nuance. “Kate was magic,” agrees Crowe. “She was, and is, a total natural. She lit up the room.”

Penny was based, says Hudson, on “an amalgamation of different women”. “We are not groupies,” Penny explains in the film. “Groupies sleep with rock stars because they want to be near someone famous. We are here because of the music, we inspire the music. We are Band-Aids.”

The woman most frequently described as Crowe’s inspiration, though, is the famous rock groupie Pamela Des Barres, who romanced, among others, Jimmy Page, Keith Moon and Frank Zappa. “I mean, Pamela is one but she’s not really who Penny Lane is,” says Hudson. “There were a bunch of different young girls who I was looking at. One was the real Pennie Lane [who formed the Flying Garter Girls Group, a group of band promoters]. Then there was this very young girl. I forget exactly which singer she used to be with, but he was very much in love with her. She was sort of like a real hippie, you know. I chatted with so many wives of the rock stars of that time. It was a wild time, and the rules were very different. [The character] sort of captured the freedom and free love and living a nomadic gypsy lifestyle in the world of rock’n’roll.”

While Penny Lane was based on a composite of real-life women, Russell Hammond was specifically influenced by Glenn Frey. Even some of the film’s dialogue was mined from Crowe’s own conversations with the late Eagles frontman. “Just make us look cool,” he once told Crowe. In the film, Russell says that same line to William.

Crudup plays Russell as an enigma: cool and breezy on the surface, but also possessed of a cruel streak and simmering self-delusion. “When I got the call from Cameron saying he was interested,” says Crudup, “he told me the character wasn’t fully developed because Brad Pitt was attached before. He would need to do some kind of workshop with the actors he thought most suitable. I’m not sure why he came to me exactly at the time. As I recall, I explained that I didn’t play guitar but that I would work diligently to fake it because that’s what actors are: we’re big fakers. I was not an Olympic runner when I did Without Limits. So I faked it.”

Realising he might have finally found his Russell, Crowe asked Crudup to fly out to Los Angeles for an afternoon. “That experience of being with Cameron,” he says, “was so infectious because he’s so curious about people and collaborative storytelling. I’m sure there’s a tape somewhere of me playing some of the scenes while doing the only thing I knew how to do on the guitar – use the E string to do the melody of ‘Smoke on the Water’. I did that for four hours while we tried to bring this character to life.

“Cameron’s challenge was finding a way to make Russell opaque enough that people were drawn to this mysterious quality in him, but knowable enough so the audience gets a glimpse of what somebody in that position experiences. He had, needless to say, volumes of information about these people that he was excited to share, and I was thrilled to soak it in. After some period of time, he gave me the part.”

Painstaking though Crudup’s casting was, it was nothing on Fugit’s. Poring over hundreds of audition tapes, Crowe was on the hunt for someone who would, in his words, “personify pure fandom and the look of a kid who’d run away and joined the rock’n’roll circus”. “Our models were Louis Malle’s protagonist in the incredible Murmur of the Heart,” Crowe wrote in Rolling Stone in 2000, “and, of course, the granddaddy of all cinema doppelgangers, Jean-Pierre Léaud, the star of Francois Truffaut’s autobiographical films.”

Eventually, he and Gail Levin happened on a tape by a kid from Salt Lake City. His name was Patrick Fugit, he was 16 and had briefly appeared in a TV movie set in Alaska called Legion of Fire: Killer Ants. Although a keen skateboarder, he wasn’t yet plugged into rock music. “He was a pure soul, an authentic Utah kid with a bowl cut and a funny, put-upon manner,” Crowe once recalled. “He waved his arms around a lot. He made us laugh. A day and a half later, he stood in my office.”

Fugit remembers finding out about the film through a friend. “He needed a ride to do this audition tape at his agency,” he says. “And I was like, ‘OK, cool,’ and I listened to him do it outside the room. Afterwards, I was like, ‘These scenes are very good – what is this film?’ He told me it’s the new Cameron Crowe movie and then had to attune me to the fact that Cameron had made Say Anything and Jerry Maguire.” Before long, Fugit himself was recording a tape. “It’s just me doing three random, rapid-fire scenes throughout,” he says. “They were all written to be about a political journalist following a politician on his campaign, because Cameron didn’t want to let on that it was about music at first.”

Two months later, Fugit received a callback. “They flew me and my mom out to LA first class and put us up in a hotel and I did my audition there,“ he says. “[She’s All That star] Rachael Leigh Cook was there doing her callback and I remember she came out of it and was like, ‘You know that feeling when you’ve just totally blown an audition?’” (She wasn’t cast.) “Anyway, I went up into Cameron’s office and I didn’t know what he looked like. But there he was, this guy with long dark hair, a T-shirt, a pair of cargo shorts on and, I think, he was in flip flops. He was super informal.”

For the first 40 minutes, though, it was not so much an audition as a pop quiz. What kind of music was he into, Crowe asked? What did he think of Led Zeppelin? What was the last record he bought? “At this point, I still thought the movie was about politics,” says Fugit, “so I told him I wasn’t into music at all. I just said that I liked Green Day and that I had a Chumbawamba CD, and he was like, ‘OK, OK, I’m going to play some music for you and I’m going to ask you about it and what it reminds you of.’ So he put on Simon & Garfunkel in his office and just started filming me.”

Fortunately, Fugit was vaguely aware of “America” and a few other songs, having heard them on road trips with his parents down to southern Utah. “Cameron described the scene of William’s older sister leaving home, which is where [“America”] ended up playing in the film. So we re-enacted that scene, with him following me around his office with a video camera. Afterwards,” Fugit recalls, “I went home for probably two or three more weeks and then they brought me out again to do some screen tests. I did some stuff with Brad Pitt, which was amazing.

“I mean, I went into Cameron’s office again and Brad was chilling there. He was super nice and could tell I was very nervous. I obviously knew who he was, and he asked me about Utah and if I snowboarded and if I liked video games. We talked about [the video game] Cool Boarders for, I don’t know, 15 minutes before Cameron turned up and we did some scenes. It was a lot of fun.”

In the end, it was Fugit’s inexperience that helped him stave off competition from the likes of Joseph Gordon-Levitt. As a piece of meta-casting, it‘s doubtlessly savvy, with parallels to William’s journey more than obvious: a credulous newcomer, trying to stay afloat in uncharted waters, surrounded by his idols. “Joe Levitt totally could have played the part and would have been brilliant,” says Fugit, “but there was, I guess, something that Cameron appreciated about how green I was.”

The resulting performance is at once tender, fearful, genuine. Speaking on the DVD commentary, Crowe said Fugit was “the embodiment of innocent fandom on the verge of adulthood. He captures how he felt. When I look at him, I remember how I felt.” “Patrick gives such a beautiful performance,” Crudup says now. “To me, working with him was one of the great charms of the whole thing.”

Clearly, it was important to Crowe that his story had verisimilitude. Before filming began, the cast were given a goodie bag filled with rock magazines from the Seventies, many of which came from Crowe’s own collection, and they were instructed to watch rockumentaries such as Mad Dogs & Englishmen (1971) – which follows Joe Cocker’s 1970 US tour – and The Song Remains the Same (1976), featuring footage of Led Zeppelin live in 1973. In the evenings, the members of Stillwater – Crudup, Jason Lee, John Fedevich and Mark Kozelek – were required to attend what affectionately became known as “Rock School”.

Its headmaster was veteran singer-guitarist Peter Frampton, while Heart’s Nancy Wilson, married to Crowe at the time, was one of the teachers. “I must confess that learning to play the guitar under that kind of pressure was not fun,” admits Crudup. “It’s one thing if I’m a guy who is not supposed to be very good, but when you’re meant to be a prodigal talent, you know, it’s hard. And I’m faking it. So your fingers are killing you, your arms are killing you, your back is killing you. And all these things are inhibiting my ability to really revel in what should have obviously been one of the most unique experiences of my professional life: getting band practice with Nancy Wilson and Peter Frampton.”

But there was a visceral thrill, he continues, in playing the San Diego Sports Arena for one of the film’s early scenes. “When you have 1,500 people with that level of adulation focused on your interpretation – even though it was pretend – it was an enormous ego boost. I can easily understand how people’s egos get widely contorted.”

Not only do Stillwater look authentic, they sound it too. Besides scoring the film and playing rhythm guitar for the band, Wilson recruited Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready to provide Russell Hammond’s dizzying riffs. Frampton, meanwhile, helped her and Crowe write Stillwater’s songs. The aim, she told EW.com, was to produce a band “that’s really good, but not all the way formed yet. An ‘opening for Black Sabbath’ kind of sound.” Deciding to eschew all the latest digital technology, Wilson achieved Stillwater’s “warmer” Seventies feel with old-style analogue mixing equipment, tube amplifiers and tube microphones. The result was pitch-perfect. Indeed, when Crowe showed Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page and Robert Plant an early cut, the pair were so impressed that they allowed the director to use five of their songs in the movie.

Of all the film’s performances, perhaps the most indelible is that of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman as Lester Bangs, the scabrously honest rock journalist who, in real life, became Crowe’s mentor. As played by Hoffman, Bangs is an empath masquerading as a misanthrope in unwashed clothes. “Phil Hoffman was sick with the flu when he shot his scenes,” says Crowe. “He had earbuds in almost every minute on set. As brilliant as you think he is, he was more. Enormous loss, and what a gift that he played Lester. Lester would probably agree. They had a similar world view… and both burned brightly… two comets streaking across the sky.”

Fugit was, by his own admission, a “little intimidated” by Hoffman. “He had a more ‘hard knocks’ type of energy around me,” he recalls. “He was like, ‘Where have you trained? You’re just some kid from Utah, huh? You’re in the real s*** now – you’ve got to step it up and earn your spot here’. He also had a talk with me about how the art of film-making was dying. It echoed what Lester was telling William about the music industry at the time. He was like, ‘You know we’re at the very end of the golden age of film-making, and soon we’re not even going to need actors because they’re going to animate everything.’ And I was 16, on set and living my lifelong dream of being an actor professionally, and he’s saying all this. I was like, ‘Wait no, I just got here.’”

While the pair were filming a diner scene, a bright set light began hindering Fugit’s performance. “It was forcing my eyes to close,” he remembers. “Philip stopped a take and he was like, ‘Hey man, you can’t even keep your eyes open. What’s going on?’” Fugit apologised. “He was like, ‘No, don’t be sorry. Can we bin that light?’ Then him and John Toll, a very masterful cinematographer, had a terse exchange. Basically, he did it to stand up for me, but he also did it as an example to show me, ‘Hey, if you are having trouble doing something, you’ve got to speak up for yourself.’”

As with Bangs’ best lines in Almost Famous (“Don’t make friends with the rock stars; they’ll corrupt your vision”), the film’s set pieces – William losing his virginity to the Band-Aids, Russell’s acid trip at a fan’s house party, a near plane crash in which the band members divulge their deepest secrets – are all rooted in fact. Yes, Crowe was deflowered by groupies, and yes, Crowe has twice nearly gone down with a plane. “That scene was based on a terrifying incident riding in a T-shirt vendor’s tiny plane on a Who tour in 1973,” he says. “It was also based on a flight with Heart.” As the band headed into a storm, “everyone’s darkest, most hysterical side came out”, Crowe once told Rolling Stone. “Afterward, I couldn’t believe that the embarrassment could be so large that living was almost second prize.”

Meanwhile, the iconic scene in which Russell, tripping on acid, climbs up on the roof of a fan’s house and yells, “I am a golden god”, is a homage to Robert Plant, who once bounded across a Hollywood hotel room during a press interview and screamed it from the balcony into the LA night. Shortly after the film’s release, Crudup was on the same flight as Plant. “I spent five hours on that plane just paralysed, looking for any attempt to strike up a conversation. When we landed, I went and got my carry-on and he looked back at me and went, ‘Oh well, that’s seen better days,’ because I guess it was a piece of s**t carry-on. And without missing a beat I said, ‘My name is Billy Crudup, I was in the movie called Almost Famous and I played Russell Hammond. I was the one who said, ‘I’m a golden god.’ He goes, ‘That’s my line’. And I said, ‘Well, it’s my line now,’ and walked off.”

Almost Famous opened in the US in September 2000. Critics, by and large, were bowled over. “Oh, what a lovely film,” wrote the late, great Roger Ebert. “I was almost hugging myself while I watched it.” The New York Times praised its “smart, expansive script”, while The Independent, reviewing it in the London Film Festival, said it was “expertly edited, deliciously funny and with a soundtrack that is better than sex”.

Yet the film failed to find an audience – and eventually topped out at just $47.4m. Partly to blame was its lack of star presence: unlike Jerry Maguire, which had Tom Cruise, Almost Famous treated Crowe as its main draw, with the barely familiar Hudson’s face dominating the poster. “DreamWorks took a pretty big leap of faith supporting Cameron in casting a completely unknown actor,” says Fugit, explaining why it didn’t set the box office alight. “Like, they could have gone with some other young very popular talented actors at the time that were right for the part. People don’t make films like Cameron makes them.”

Although it may not have been as commercially successful as Jerry Maguire, Crowe says that, even to this day, it’s Almost Famous that people most want to talk to him about. A big-hearted, multi-generational antidote to po-faced artistic pretensions, it found a second life on DVD and was last year turned into a well-reviewed Broadway musical. While largely remaining true to the plot of the film, the play opted to tweak two problematic aspects of the original story. Gone is any suggestion that Penny Lane might be as young as 16; what’s more, William no longer kisses her when she’s unconscious, having overdosed on Quaaludes.

Hudson, on whom Fugit admits he had a crush, says she never felt “weird” or “uncomfortable” about that kiss. “It was quite innocent actually, but you know, we’re in sensitive times and if people feel it’s necessary to be ultra-sensitive and not upset anybody, then yes, that’s the right choice. I do think there are circumstances in the business right now that are overly sensitive.” Viewed today, the scene “might be problematic”, says Fugit, but “Crowe has this way of taking an authentic look at some impulses that make you squeamish later down the line. I’m not saying that compares to kissing somebody while they’re high on Quaaludes, but we’ve all done or said things that 20 years later make us squirm.”

For Hudson, the whole experience of Almost Famous was “magical”. Of the many fond memories she has on set, the one that sticks out the most, she says, happened on the final morning. “Jason Lee and everybody were going out,” she recalls, “and I had to do a really early shot in Central Park at 6am the next morning. It was my final scene, So I ended up pulling a total all-nighter with the boys and I’m sneaking back to my bedroom, which is next door to Cameron. There’s like four of us outside my room and I can’t get my key to work, and I’m there, in a really pretty little dress, clearly just getting home at 5am. Cameron hears and gets up and looks at me. Then he just goes: ‘Rock’n’roll.’”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments