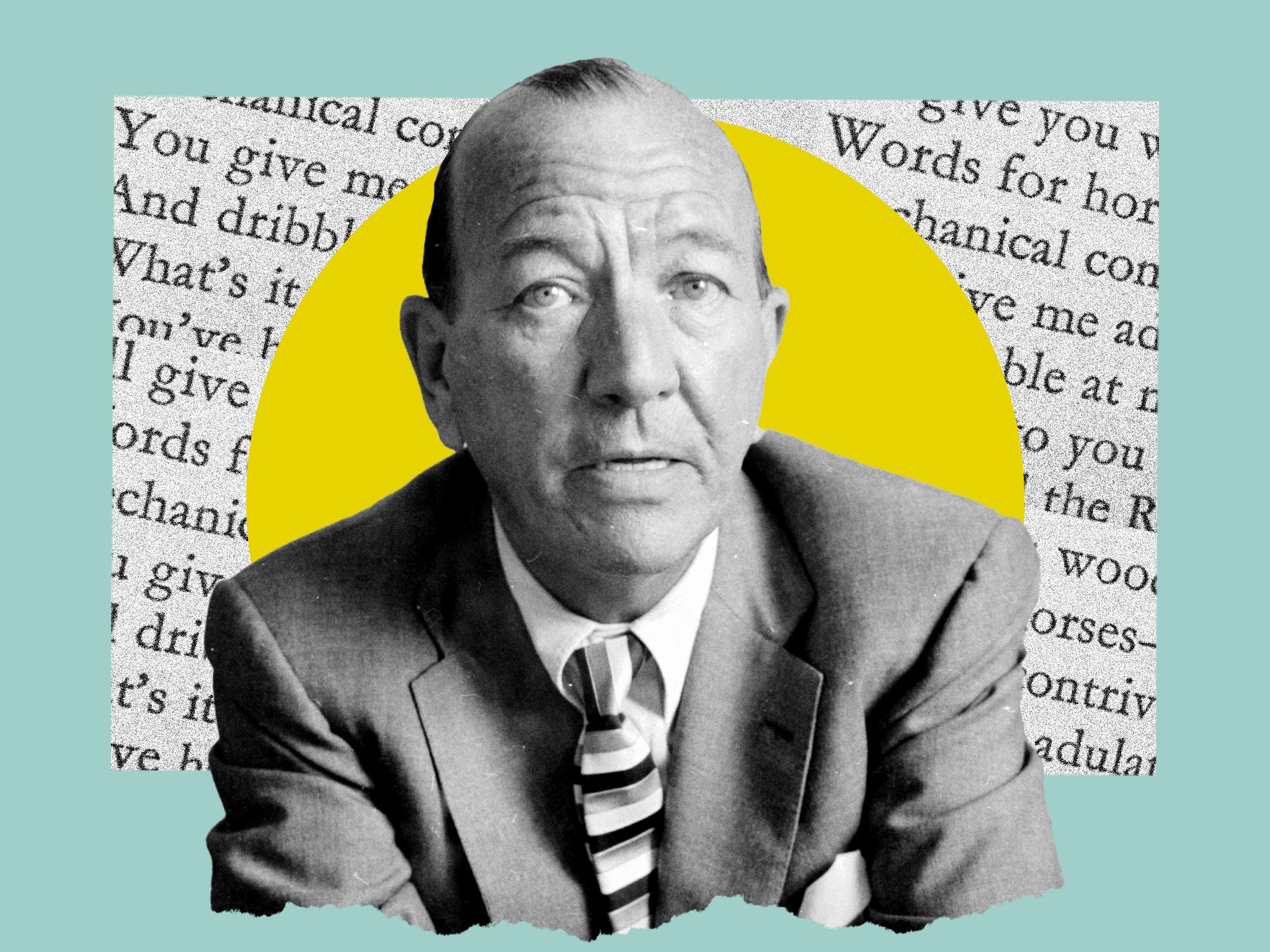

‘I’m an enormously talented man’: The life of born show-off Noel Coward

As a major new biography about Noel Coward is published half a century on from his death, Martin Chilton looks back on the life of the trailblazing playwright with ‘a talent to amuse’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I’m an enormously talented man, and there’s no use pretending that I’m not,” Noël Coward once said. The trailblazing playwright may not have been humble, but he was correct. Since his death at 73, half a century ago today, his words and music have not lost their capacity to dazzle audiences around the world with their crisp wit and sense of mischief.

Coward’s brag, long after he was acclaimed as a playwright, composer, novelist, singer, painter, librettist, stage producer, film director and cabaret artist, typified the bravado of a born show-off, a polymath who insisted his main concern was that “you must never, never, never bore the living hell out of the public”.

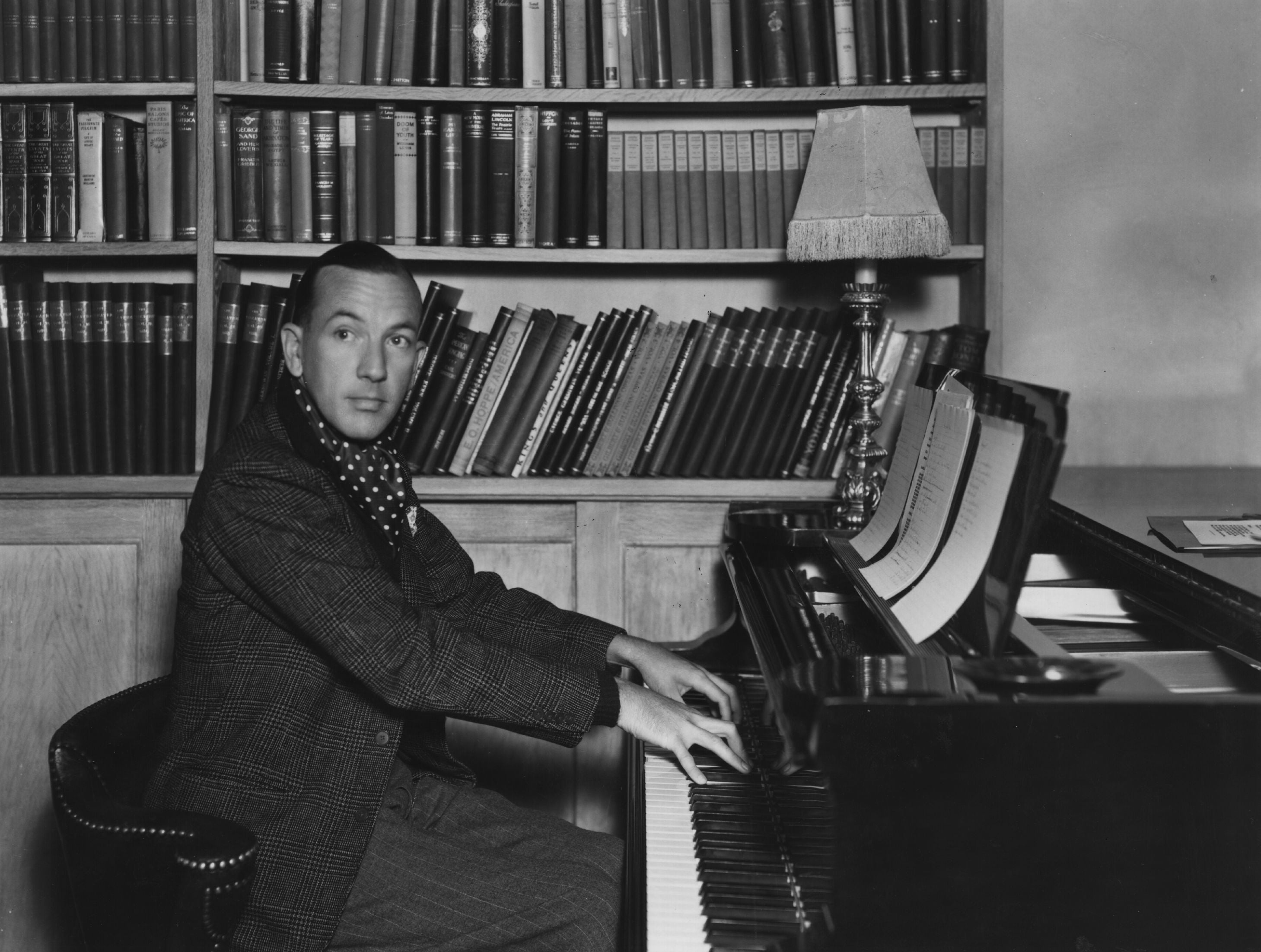

He lived up to his own advice: the finest of his 57 published dramas, musicals and revues, including Hay Fever, Private Lives, Blithe Spirit, Cavalcade and the operetta Bitter Sweet, stand the test of time. Although he could not sight-read music, Coward was a gifted composer, and his 281 songs include the classics “Someday I’ll Find You”, “Mad About the Boy” and the sardonic “Mad Dogs and Englishmen”. The 1942 war film In Which We Serve, which earned him an honorary Oscar, and his screenplay for David Lean’s romantic classic Brief Encounter, based on his one-act play Still Life, are further evidence of a titan of 20th-century culture.

Yet beneath the well-known image of a quick-witted, jaded sophisticate, lurked a troubled man, full of contradictions, traits evident in Oliver Soden’s excellent Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). The new biography contains revelations from Coward’s unpublished diaries and correspondence, and spotlights, as Soden puts it, “a man of surprising gravity and bleakness”.

Born on 16 December 1899 in Teddington – and named for his birth’s proximity to Christmas – he was the son of piano salesman Arthur and doting mother Violet. Among their quirks were being fervent “anti-vaxxers”; their refusal to inoculate Noël against smallpox earned them a 10-shilling fine in 1901 (three years after their six-year-old son Russell died from meningitis).

The young Coward, who grew up near Battersea Park, was a skilful petty thief, describing himself as “a brazen, odious little prodigy”. By force of will, he forged a career as a child actor, but writing was his true gift; by 18 he had an unpublished novel and play under his belt.

Although Coward’s dramas hardly cause a commotion nowadays, in the era following the First World War they had a blistering impact, shocking and titillating audiences. The Vortex, staged in 1924, explored amoral characters who dared to talk about extramarital sex, freedom and truth. The Telegraph dismissed it as “diseased” and provocative lines about drugs and homosexuality were cut by the Lord Chamberlain.

A year later, in Easy Virtue, Larita Whittaker, a divorcée rejected by a “respectable” middle-class family, exclaims: “I don’t live according to your social system. I have a perfect right to say what I like and live how I choose.” Coward’s portrayal of sexually liberated women challenged the status quo but appealed to Alfred Hitchcock. The young director adapted Easy Virtue into a silent film, keeping a titled card on which Larita is asked whether she’s had “as many lovers as they say?” With 1926’s Hay Fever, a sell-out play written in three days, Coward became the highest-paid writer in the world. Controversy made for booming box-office business.

After a trip to America in 1926, Coward cabled The New York Times suggesting censorship was an attempt to impose “sterile” drama on the public. A book of essays written after the trip, Anglo-Saxon Attitudes, explored birth control and what he described as the “fatal curse” of marriage. The book never saw the light of day. Semi-Monde, which depicted bisexual love triangles, was not staged until 1977. When his actress friend Billie Carleton died of a cocaine overdose at 22, it inspired Coward to write The Dope Cure, a play still in the archives. Private Lives, his resonating dark comedy from 1929 that explored atheism, adultery and domestic violence, is being revived at London’s Donmar Warehouse in April 2023. The revival follows on from the popularity of the 2019 National Theatre production of Present Laughter. After winning an Evening Standard Theatre Awards Best Actor trophy for playing the mordant matinee idol Garry Essendine, Andrew Scott said: “I’d like to thank Noël Coward himself. I think sometimes he’s accused of being a dusty old playwright but he smuggles, through comedy, really modern ideas about sexuality and gender. He sort of says it’s OK to live a life that’s less ordinary.”

Coward was ahead of his time (as his song “I Wonder What Happened to Him?”, about sex-realignment surgery, demonstrates) and Masquerade presents the serious-minded workaholic beneath the louche image. “Work is much more fun than fun,” said the man who wrote nine plays, including Still Life, in the summer of 1935. He had a frenetic imagination, penning “I’ll See You Again” in minutes while his taxi was stuck in a jam. The song became a standard, recorded by Frank Sinatra and Bryan Ferry.

In the 1930s, Coward perfected the image of a dandy, sporting a silk dressing gown or maroon velvet smoking jacket at home (while sipping a vodka martini), or wearing a double-breasted Dior tuxedo, with a florid buttonhole, out in public. He was usually photographed with a cigarette holder (smoking was a common motif in his plays) and once sparked a fashion craze for turtleneck jerseys.

Although Coward’s sexuality was an open secret within the arts world, he was wary about publicising his private life at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in England (that did not change until 1967). In May 2022, Russell Jackson, emeritus professor of drama at Birmingham University, revealed that in the 1960s Coward worked on two plays that openly featured same-sex relationships. “I was surprised to find Coward wanted to deal more frankly with homosexuality than he had ever been able to before in a play,” said Jackson.

Coward hid in plain sight. A photo album compiled in the 1930s by his friend Joyce Carey came to light in 2020, showing Coward and his friends at Goldenhurst, his country retreat in Kent. There are shots of lovers such as Jack Wilson, Graham Payn and Alan Webb in tightly clinging woollen swimming trunks (Julian Clary, who later bought Goldenhurst, wrote a novel wittily entitled Briefs Encountered). Actor Payn, mocked by Coward as “an illiterate little sod who only reads trash”, was the star’s companion for three decades, eventually managing his estate.

Coward had a one-night stand with writer Gore Vidal and a tempestuous wartime affair with married actor Michael Redgrave. Once, crossing Leicester Square with a friend, Coward spotted a cinema marquee advertising Redgrave and Dirk Bogarde’s movie The Sea Shall Not Have Them. Coward turned to a friend and quipped, “I don’t see why not. Everyone else has.” He loved exchanging gossip about sex, telling writer Truman Capote that Edward VIII hated him “because I’m queer and he’s queer but, unlike him, I don’t pretend not to be”. He also described American divorcée Wallis Simpson as the King’s “fag-hag”. Yet Coward was a paradoxical, complex man, remaining friends with the homophobic Ian Fleming, whose James Bond novels lampoon weak-willed “pansies” and refer to gays as “sexual misfits”.

Fleming admired Coward’s writing, as did HG Wells and TS Eliot. In 1964, the poet said: “There are things you can learn from Noël Coward that you won’t learn from Shakespeare.” Coward was also friends with Evelyn Waugh, that “strange little man”. Coward, an agnostic, was intrigued by Waugh’s Catholicism. “I have always been mystified how anyone as intelligent can accept the dogmas of the RC faith,” he wrote. When he quizzed Waugh, the Brideshead Revisited author admitted to being a “bored and unhappy man”. One of Coward’s most comical collisions was with macho Ernest Hemingway. “Hemingway found Noël’s gossipy conversation unbearable, and fled his company,” writes Soden.

The biography adroitly pieces together Coward’s activities during the Second World War, when he secretly spied for British Intelligence in Paris – “I’m stuck among upper-class twits,” he wrote – then reported directly over drunken private dinners to prime minister Winston Churchill and US President Roosevelt.

His war experiences left indelible memories, some brutal, some comic. “He never forgot the sight of Coco Chanel entering a Paris air raid shelter followed by a maid who carried a gas mask on a velvet cushion,” records Soden. Coward’s London home was destroyed by a 1941 Nazi bombing raid. He overheard two women clacking their high heels through the rubble of The Blitz. “You know, dear, the trouble with all this is you could rick your ankle,” one said. Despair immediately turned to laughter.

He was outraged the same year when the BBC (missing the satire entirely) banned his song “Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Germans”, writing a self-aggrandising letter to his friend Esmé Wynne saying: “It’s too, too horrid. Everyone is being nasty, accusing me of doing nothing for the war effort and I’m not allowed to say I’m one of the government’s top-secret agents?”

The ever resourceful Coward transformed his image by writing, producing and co-directing In Which We Serve, which was nominated for Best Original Screenplay in 1943. Coward was further vindicated when it was revealed he was on a secret Gestapo death list.

His masterpiece Blithe Spirit – which he considered “technically my best piece of writing” – was completed in eight days, in the aftermath of the London bombing. It remains one of the funniest British dramas of its era, hailed by George Orwell as “a devastating satire on spiritualism”. Lean’s 1945 film starred Margaret Rutherford as Madame Arcati, a role taken by Judi Dench in the 2020 remake. Coward’s hilarious mystic has also been portrayed on stage by Beryl Reid, Alison Steadman, Angela Lansbury and Jennifer Saunders.

Blithe Spirit marked an artistic high point for Coward, whose prodigious post-war output met with mixed results. His 1950’s play Flight of Fancy is one of 30 abandoned or incomplete scripts in the archives, while works such as Quadrille and Relative Values received tepid reviews. Coward lost money on a disastrous musical called Pacific 1860 and moved to Jamaica and Switzerland to avoid UK taxes. He relied on cabaret shows at the Desert Inn in Las Vegas (which paid £375,000 a week in today’s money) to maintain his lifestyle, entertaining those he dubbed “Nescafé Society” with songs such as “London Pride” and “Don’t Put Your Daughter On The Stage, Mrs Worthington”. The latter – written on the boat home from a sex tourism trip to Shanghai – was prompted by being pestered by parents with theatrical ambitions for their children.

Despite the Vegas popularity, he began to seem out of touch, spouting increasingly reactionary views and casual racism from a bygone era. Yet his flippant wit remained. His nickname for Joan Hirst, his secretary for 25 years, was “Stop and Fetch”, and he demanded acolytes call him “The Master”, a sobriquet from actor John Mills. Wilson also claimed credit, insisting the nickname was sarcastic. Coward, who encouraged his mother to maintain a scrapbook recording “Masterisms”, might not have cared. His generosity and charm meant friends and colleagues put up with his tantrums, selfish behaviour and capriciousness.

Coward turned down playing Bond villain Dr No and the predatory Humbert Humbert in Lolita, although he jumped at portraying the spy Hawthorne in the 1959 adaptation of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana. A decade later, he appeared as criminal mastermind Mr Bridger in The Italian Job. “He had a presence,” said co-star Michael Caine. The pair, who loved chatting about their eventful south London backgrounds, became friends. “The most British thing I ever did was go to the Savoy Grill and have dinner with Noël. He was so funny. He used to take the p*** out of everybody,” recalled Caine. In 1970, Coward was knighted, joking “in my dotage I have become a national treasure”.

Coward’s memorial at Westminster Abbey is inscribed to “A Talent to Amuse”, a tribute that underplays his ground-breaking work, the product of a restless, questioning mind. His friends knew about his mental health problems, when he was consumed by feelings of futility, and late in life he wrote to Gladys Calthrop offering darkly Cowardesque advice about existence to his old friend: “Don’t go c***ing about saying nothing is worthwhile, because we all know bloody well that it isn’t, but there’s always an apple and a good book”. We can all still learn from Coward, a man who said, “it’s discouraging to think how many people are shocked by honesty and how few by deceit.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments